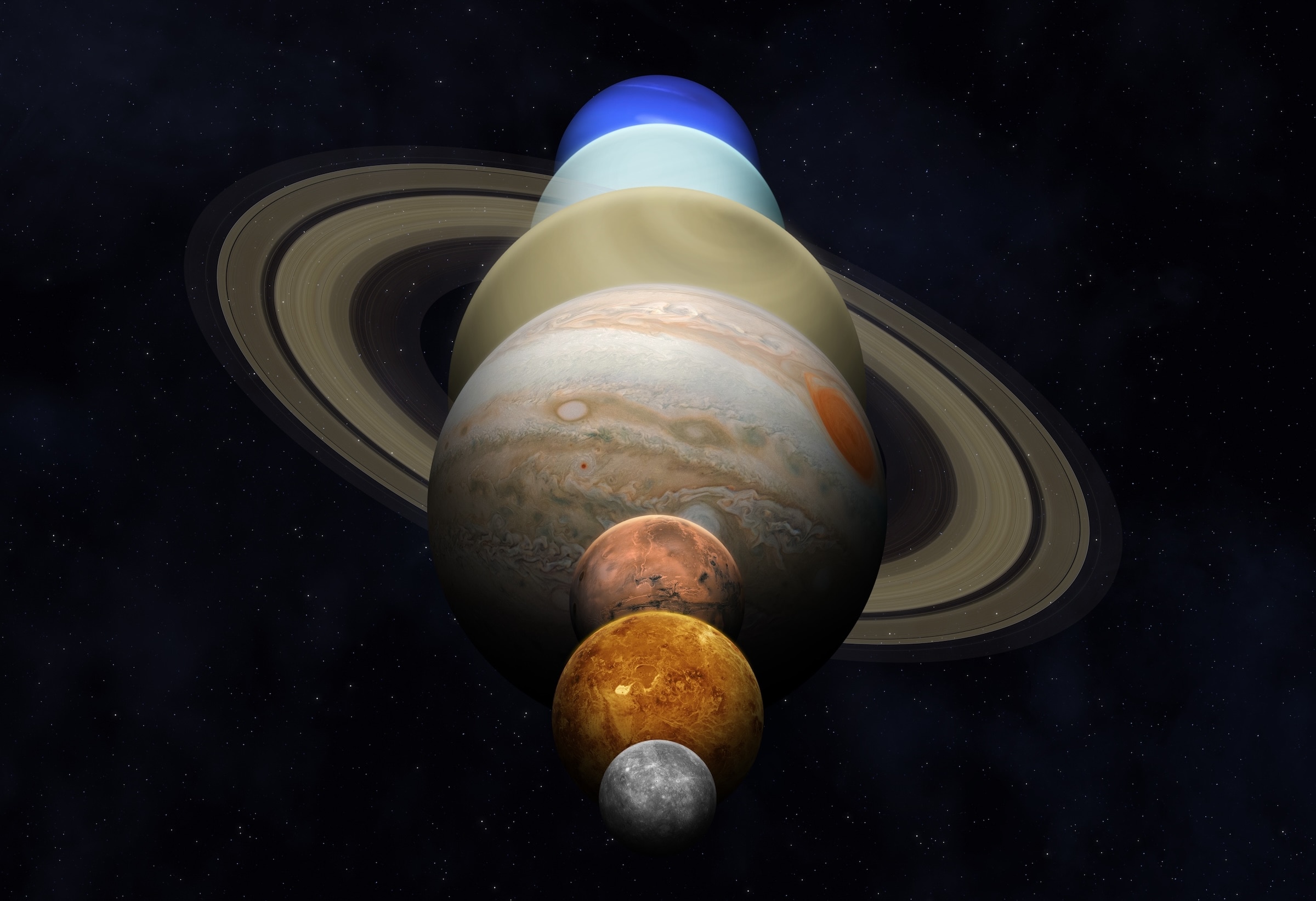

© Shutterstock

In the final installment of this series, we examine how the Holy Qur’an inspired and invigorated centuries of Muslims scientists to uncover the mysteries of the cosmos.We dive into why this cosmological renaissance was passed on from the Muslims to the Europeans, and how Islam can claim its stake in the future of science.

Humanity’s understanding of the heavens and the earth was a gradual evolution. We know that this tradition was passed from the Babylonians to the Greeks. The Babylonians had mapped out the stars, noticing their circular motion with respect to the earth around the polar star. The Greeks would apply a cosmological or structural definition to this motion, splitting the heavens into celestial spheres upon which the heavenly bodies moved. Greek thought would come to be dominated by Aristotle, a student of Plato, who himself was a student of the Prophet Socrates (as).[1] However, they would be puzzled by ‘Five Wandering Stars’ to which they could not apply a satisfactory model accounting for their motion; in an attempt to resolve this enigma, their cosmological theories would further develop, culminating in Ptolemy’s work, the Almagest.

However, this work lay lost, until the arrival in the desert of an unlettered Arab who would relight the torch of knowledge. Amongst his followers a movement was borne, which sought out and combined the knowledge of whichever nation they came into contact with, fulfilling the words of the Prophet (sa) that ‘wisdom is the lost treasure of a believer’[2] and to ‘seek knowledge even as far away as China.’[3] Within the first three centuries of the Prophet’s (sa) death, they had collated the knowledge of the Greeks, including the Almagest, and began a critique of Ptolemaic models – led by the great Ibn al-Haytham.

In this regard, this movement bore many similarities to Islam, in that Islam was both an amalgamation and enhancement of the best of the religions that came before it. Similarly, in the field of secular knowledge, Islam unified and merged the various scientific endeavours taking place in different parts of the world, and offered valid critiques, although it cannot compare to the level of transformation that Islam brought about on the religious plane. This was due to the fact that after the first three centuries of progress, Muslims began to gradually ignore the Qur’an as the motivating force in their lives.

The work of the Muslims then bifurcated into two streams: East and West, all the while trying to resolve this enigma of the ‘Five Wandering Stars’. Whilst the East concentrated on removing the equant, eccentricities and reformulating Ptolemy’s model into one of true uniform circular motion, finally succeeding with Ibn al-Shatir’s models, the Western Andalusian Muslim scientists desired to completely remove all epicycles and eccentricities from the Ptolemaic system and move to a concentric solar system.[4] As such, during this period, many different theories were investigated and proposed until we finally reached the final act of Islamic astronomy, with the foundation of the Samarkand observatory by Ulugh Beg of the Berlas Tribe. Ali Qushji, one of his students, would resolve the motion of the inner wandering stars with an eccentric model, a model which would provide the keys to the heliocentric theory.

The world would go through tumultuous changes during this time: Constantinople would fall to the Muslims, but Andalusia (Spain) would fall to the Christians. At the same time, the age of the printing press would dawn. During this period, a fresh translation or commentary of the Almagest would be called upon by Cardinal Bessario, a refugee from Constantinople, labelling it as a new ‘crusade’[5]. The resulting work was entitled the Epitome of the Almagest, which was constructed by Peuerbarch and Regiomontanus, combining the Almagest and previous Muslim thinking on the subject. Furthermore, within the Epitome, Regiomontanus would also describe an eccentric model of the inner wandering stars, a concept he may or may not have developed independently of Ali Qushji. Copernicus would then use the parameters from the Alphonsine tables – based on previous Muslim astronomical tables – and apply it to this eccentric model of the inner wandering stars, leading Copernicus to the theory of heliocentricity. Copernicus’s work was then taken up by Brahe, who turned his attention to gaining more accurate results of the heavens, possibly using knowledge from Islamic scientists to develop his instruments. Using these new observations and in particular one wandering star (Mars), Kepler was inspired (by Al-Zarqali’s work, according to some) to apply an elliptical treatment to the orbit of Mars, and then by extension, to all the wandering stars, around the sun, rather than around a false centre, or the Earth.

At the same time as this development, Galileo pointed a telescope to the heavens, which was possibly based on optical theory developed by the Muslims, and presented new laws of motion, again possibly rooted in Muslim thought, which effectively ‘laid the heavens bare.’ Together, these changes resulted in the crumbling of the old edifice of Aristotelian physics and cosmology. As such, a new edifice was required, a new model to describe why the wandering stars moved in an elliptical fashion; and it was this new model that Newton finally provided, and the enigma of the ‘Five Wandering Stars’ was finally complete, and with it, a new day began to dawn.

A Qur’anic Prophecy Par Excellence

During the investigation of this subject, I was overawed by the majesty of God when I realised that the Enlightenment period and scientific revolution are beautifully captured in Chapter 81 of the Holy Qur’an, Surah al-Takwir; in fact, so exact was the match, that I began to shed tears at the beauty of the Qur’an.

Chapter 81, of all the chapters of the Qur’an, possesses a unique relationship with the modern age. Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (ra), the Fourth Caliph of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, in his book Revelation Rationality, Knowledge and Truth details [6] how this chapter captures the revolutionary changes of the modern era. The chapter, from verse 1 to 22, is as follows:

In the name of Allah, the Gracious, the Merciful.

When the sun is wrapped up,

And when the stars are obscured,

And when the mountains are made to move,

And when the she-camels, ten-month pregnant, are abandoned,

And when the beasts are gathered together,

And when the seas are made to flow forth one into the other,

And when people are brought together,

And when the girl-child buried alive is questioned about,

‘For what crime was she killed?’

And when books are spread abroad.

And when the heaven is laid bare,

And when the Fire is caused to blaze up,

And when the Garden is brought nigh,

Then every soul will know what it has brought forward.

Nay! I call to witness the planets that recede,

Go ahead and then hide.

And I call to witness the night as it passes away,

And the dawn as it begins to breathe,

That this is surely the revealed word of a noble Messenger,

Possessor of power, established in the presence of the Lord of the Throne,

Obeyed there, and faithful to his trust.[7]

In this chapter, the salient features of the scientific and social revolution that occurred following the Enlightenment period are prophesied, around 1,000 years prior to their occurrence. The series of prophecies end with an astounding statement that strikes to the very heart of the history of the heliocentric discovery.

Firstly, the sun and moon being wrapped up are esoteric terms relating to Islamic symbols: Prophet Muhammad (sa) and his companions, respectively. It indicates an age of spiritual degeneration. Then come the literal prophecies, in startlingly quick succession.

First is described the movement of mountains, describing the clashing of great worldly powers in the Arabic idiom:

‘And when the mountains are made to move.’

Indeed, it was the fall of Constantinople in 1453 that marks the point at which ‘the worldly powers are made to move’, and it is a consequence of this perturbation that Cardinal Bessario directs the new translations of the Almagest from Peuerbarch and Regiomontanus.

Then, in a sequence of six verses between verses 11 to 19 in this Chapter, we find an almost exact description of the salient features of the modern era that were to occur.

We read next of the abandonment of the camel, the most crucial animal to the Arabs, as a means of transport:

‘And when the she-camels, ten-month pregnant, are abandoned.’

Thereafter is described the gathering of animals as a practice in zoos, relating to a curiosity in the natural world, being born:

‘And when the beasts are gathered together.’

The flowing of seas into each other, as occurred with the Panama and Suez canals, is then described:

‘And when the seas are made to flow forth one into the other.’

Thereafter, the increase in communication in an age that would make a global village of the world, is described:

‘And when people are brought together.’

Thereafter, the social change relating to women’s rights is brought to focus:

‘And when the girl-child buried alive is questioned about,

“For what crime was she killed?”’

In the next verse, attention is turned to the role literature and writing would play in that age, with books being spread abroad to an extraordinary extent:

‘And when books are spread abroad.’

Indeed, the printing press was invented in the 1440s by Gutenberg, and the first scientific printing press is established by Regiomontanus in Nuremberg in the 1470s.8 It is directly following the printing press that we see a step change in the intellectual and scientific progress of humanity: ‘Every step of the remarkable “adventure in ideas” which took educated Europeans from the Almagest to the Principia [9] in less than two centuries was marked by the “practice of…putting manuscripts into print.”’[10] Prior to the printing press, whether we examine the Greek or the Muslim period, it takes centuries for ideas to develop. When we look at Europe itself, those same scientific ideas that had been developed following the printing press had reached Europe in the 10th–13th centuries. But it is suddenly with the arrival of the printing press that an exponential progress in science is triggered, after which, in just two hundred years, the scientific revolution, beginning with heliocentricity and Copernicus, through to Kepler, Galileo and finally to Newton, is completed.

We can draw an analogy of the printing press with the modern-day computer. A computer’s processing power increases with the concentration of transistors – in a similar manner, the printing press exponentially magnified the number of brains processing any given piece of information at any one time, as such knowledge was able be to be disseminated widely to many people at one time, and then progressed by an increasing number of people at any one time. Indeed, we see that Regiomontanus’s Epitome of the Almagest is published, and it becomes a primary source of information for Copernicus. Copernicus himself reputedly receives a published copy of his own book on his deathbed. This book then rapidly spreads amongst the scholars and thinkers of his time. It comes into the hands of Brahe and Kepler, who are inspired by its arguments to further investigate the heavens. Kepler himself, when investigating the orbits, comes across contemporary works on magnetism in printed form and works on logarithms, again in printed form, from which he is further able to elucidate his ideas. Furthermore, the works of his contemporary Galileo reach him through the book entitled A Message from the Heavens. One can see that the ease and speed with which ideas are spread ignites a revolution in learning.

Thereafter, immediately following the description of the spread of books from the invention of the printing press, an extraordinary statement is made:

‘And when the heaven is laid bare.’[11]

This occurs metaphorically through the works of Copernicus and Kepler, who resolve the motion of the wandering stars: Copernicus centering the motion of the solar system around the sun in the early 16th century, and Kepler resolving the motion of the planets in the form of ellipses at the beginning of the 17th century. Furthermore, it is also fulfilled literally through Galileo’s telescope in the same period, who shines the telescope into the heavens.

Finally, God, speaking through an illiterate Arab of the 7th century, calls to witness that all these matters will certainly happen, and the testimony God puts forward is the following:

‘I call to witness those planets that recede, go ahead and hide,’[12]

The greatness of the prophecy becomes undoubtable when God bears witness by those same ‘stars’ – the wandering stars which sometimes appear to travel backwards in the night sky and the same wandering stars that began the investigation into the heavens in the first place. As has been clearly shown throughout these articles, it was the solution of this conundrum that ushered in the scientific revolution. In particular, as has been stated earlier, it was the resolution of the motion of Mars, more than any other heavenly body, which clearly displayed this behaviour, that was the key to Kepler’s discovery of elliptical orbits. The verse continues:

‘And I call to witness the night as it passes away’ [13]

Once the resolution of the motion of these wandering stars was complete, it shattered the old Aristotelian worldview, as if taking humanity out of darkness just as the night passes away.

‘And the dawn as it begins to breathe’ [14]

It would be Newton and his description of the ‘Law of Universal Gravitation’ in Principia which would finally complete the scientific revolution, resolving the enigma of the wandering stars by explaining how the wandering stars and planets moved in an elliptical motion. As this revolution was complete, a new day would begin to dawn in humanity’s progress, as stated in this verse. Indeed, how beautifully verses 18 & 19 of the Qur’an are inadvertently captured on the epitaph of Newton:

‘Nature and Nature’s Laws lay hid in Night: God said, “Let Newton be!” and all was light.’[15]

In this chapter, God informs us of an age and civilisation in the future that possessed new forms of transport, created zoos, analysed the biological world, pushed forth women’s rights, printed books en masse, created entire canals between seas, and other essential changes. All these changes followed from the scientific revolution, and the scientific revolution was itself triggered by the heliocentric model, key to which were the motions of the wandering planets.

To cite the wandering planets themselves as proof and as testimony that the prophecies of the chapter would be fulfilled, is such a grand and extraordinary demonstration of the truth of Islam and of the Prophethood of Muhammad (sa), that one is bereft of words. How could this have originated from the mouth of anyone but God? Who knew what lay hidden in the womb of the future, and who knew the observation that would trigger the entire scientific revolution, which underpinned the scientific and social changes prophesied in the chapter?

A fool could argue that the prophecies of the chapter were guesswork. But only a madman, after understanding the significance of the wandering stars for the heliocentric model and their significance in the scientific revolution, could claim these verses could originate from the mouth of anyone but God. Thus, in conclusion to all this, the Qur’an states in verse 20:

‘That this is surely the revealed word of a noble Messenger’ [16]

Why Did the Muslims Not Own the Renaissance?

The remaining question pertains to how much of the scientific revolution was owed to Islamic science and why the Muslims did not own the revolution.

In answer to the first part of this question, unfortunately, this has usually been answered with two extreme views: some say that everything was based on Greek science, while others say that everything was owed to Islamic science and plagiarised by the West. I believe these are both simplistic opinions and also belie a lack of understanding of how science progresses, in that its progression is not always linear. Furthermore, scientific progress is not always a revolution based on the works of one person (although it may seem as such); rather, a plethora of discoveries and objections are raised, which in the end lead to the overhaul of the preceding understanding. As Newton himself stated: ‘If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.’[17]

We find that after the death of the Greek scientific tradition, three steps were required for a scientific revolution:

Step 1 – A regeneration of Greek science. As explained previously, Greek science had died. As such, the first step would be to re-understand the terminology, theorems and proofs being discussed, rather than just a simplistic translation as one could do with a non-scientific text.

Step 2 – Once Greek science was sufficiently understood, the next step would be to critique it and then set the parameters for a new understanding.

Step 3 – The final step would be to formulate new models and understandings of the world.

We can clearly see that steps 1 and 2 were achieved by the Islamic civilisation, and step 3, the completion of the revolution, would be achieved by the Western European civilisation.

The second part, pertaining to why the Muslims did not own the revolution and complete all three steps, is an interesting question. Firstly, as I have already pointed out, the step change in the evolution of knowledge occurs directly following the invention of the printing press. This is the key point, which marks a change in pace and acceleration of learning between Europe and the outside world.

Secondly, at the beginning of Islam, especially the first three centuries, we saw an explosion of intellectual activity. During this period, the entire Greek tradition was not just being translated, but was actually being regenerated, following which, as would be expected, a critique ensued of the Greek masters. Thereafter, there was a definite slowing of pace; although significant discoveries were made both in Western and Eastern Islam; in the East the tradition was kept alive by the Maragha astronomers, and in the West, it began to peter out in the 13th century, coinciding with the beginning of the gradual demise of the Islamic empire in Spain (which eventually ended in the late 15th century).

Thirdly, it seems in some areas of the Islamic thought there was not a robust enough challenge to Aristotelian physics and cosmology.

Lack of Challenge to Aristotle

Islamic science was full of challenges to Greek thought; indeed, it was this challenge that eventually ushered the scientific revolution. However, it does seem that at some point, Greek works, in particular those of Aristotle, began to take on a near mythical status.

The reformer Al-Ghazali (C.E. 1056) – who is unfairly demonised in the West as someone who precipitated a decline in Islamic science – tried to redress this balance. He condemned the overreliance on Greek thought:

‘The heretics in our times have heard the awe-inspiring names of people like Socrates, Hippocrates, Plato, Aristotle, etc. They have been deceived by the exaggerations made by the followers of these philosophers – exaggerations made to the effect that the ancient masters possessed extraordinary intellectual powers: that the principles they have discovered are unquestionable: that the mathematical, logical, physical and metaphysical sciences developed by them are the most profound…’[18]

Al-Ghazali makes a distinction between observational truth and theoretical or metaphysical truth, specifically the difference between astronomy and cosmology, so to speak. For example, he says:

‘…if their metaphysical theories had been as cogent and definite as their arithmetical knowledge is, they would not have differed among themselves on metaphysical questions as they do not differ on the arithmetical.’[19]

It is fascinating that he called for a challenge to Ancient Greek cosmological thought rather than a challenge to their mathematical calculations, which was exactly what brought about the scientific revolution in the West.

Muslims considered the Holy Prophet Muhammad (sa) as the sun of the spiritual world and the Holy Qur’an as containing the very words of God Himself. Yet at some point, it seems that some areas of Muslim thought had set up equals to the Prophet (sa) and the Qur’an in the form of Aristotle and Greek works, almost assigning a mythical status to the latter. However, what these Muslims seemed to have forgotten was that the spiritual and material worlds are two sides of the same coin. By understanding the spiritual, one can also gain insight into the material. As such, some Muslim scholars did not realise that they possessed both a spiritual and material sun in the form of the Holy Qur’an, and they should have turned to it for inspiration and guidance. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (as), who is the founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, writes in his commentary of the Surah al-Fatihah, the opening chapter of the Holy Qur’an:

‘The truth is that Surah al-Fatihah encompasses every science and every insight and comprises all points of truth and wisdom and answers the query of every seeker and overwhelms every assailant.’[20]

Clues in the Holy Qur’an Pointing Towards the Heliocentric Model

The Christian world’s main problem with heliocentricity stemmed from scripture. Muslims, on the other hand, were gifted with a text which was the perfect and unchanged word of God.

The fact is, a literal reading of the Holy Qur’an makes for a stark antithesis to Aristotelian cosmology. I will try to present the facts as they would have been seen in medieval times, rather than using the benefit of hindsight.

Heavenly Orbs

The Holy Qur’an clearly talks about seven heavens in many places. An amateur researcher may take this as an homage to Aristotle’s heavenly spheres. However, with a little more than a cursory glance, one discovers a key difference. According to the Holy Qur’an, the lowest or nearest heaven to the earth is adorned with the stars and light-giving objects[21]. This is the most straightforward reading of the verse, and in one sentence, it demolishes Aristotle’s cosmology. In Aristotle’s cosmology, the last sphere, the last heavenly orb, is adorned with stars – not the first. If we take the words used literally, then the verse is stating that all light-giving objects occupy the lowest heaven, which implies there are no orbs!

Immutability of the Universe

One of Aristotle’s prepositions is that the Universe is immutable and does not change. Yet the Holy Qur’an clearly states that the heavens are expanding: ‘And We have built the heaven with might and We continue to expand it’. [22] In fact, a number of Muslim scientists indeed challenge Aristotelian thought on this issue, taking inspiration from the Holy Qur’an.

The Motion of the Earth

A key part of the heliocentric jigsaw was the recognition that the Earth is in motion. And according to the following two propositions mentioned in the Holy Qur’an, at the very least, a Muslim scientist should have considered that it is plausible that the Earth moves. For example, in a number of verses of the Holy Qur’an, God describes the mountains as ‘rawaasiya, which means firmly rooted in the earth,’[23] but at the same time, the Holy Qur’an also states: ‘The mountains that you see you think are stationary while they are constantly floating like the floating of clouds.’[24] When you put the two propositions together, the only logical outcome if the mountains are both firmly rooted in the earth and at the same time floating like clouds, is that the earth itself is in motion. How this was missed goes to show there was no serious attention paid to the Holy Qur’an by Muslim scientists.

Heliocentricity

Finally, and most simply of all; the religious theology of Islam points towards a heliocentric universe. Just as from a Christian theological perspective it makes perfect sense to put the earth at the centre of the Universe as it is the birthplace of the ‘Son of God’; it is with great surprise that Muslims never applied their own religious theology to the heavens. According to Islamic religious theology, the centre of the spiritual universe is Muhammad (sa) – and he is also commonly known in Islam and referred to in the Holy Qur’an as al-Shams, the Sun! It is surprising that no Muslim ever thought of putting two and two together.

The Future of Islamic Science

There is a danger here that all Muslim scientists should be aware of, that to infer something from scripture is different from becoming absolutely wedded to that inference, as if the inference is itself inherently the truth. The Holy Qur’an is the Truth, but the inference is our own insight, reasoning and knowledge, wedded to the Truth – and as it contains part of ourselves, it may also contain falsehood.

However, what I am pointing to is the fact that scientific research is fuelled by the imagination. Indeed, a theoretical physicist may have hundreds, if not thousands, of ideas, some of which he will pursue and most of which will result in dead ends. For these clues and ideas, Muslims should be searching the Holy Qur’an, and it is these clues which would have provided a shortcut to the scientific revolution.

The advantage of the Muslim scientist was in stark contrast to the Christians of the Enlightenment period; their development of science met an almost insurmountable obstacle: The Bible. So great was this threat that in Copernicus’s original work, the printer included additional material in the preface to protect him from the wrath of the Church. Galileo was not so subtle, and it took several hundred years for him to be forgiven. Eventually, this giant obstacle could only be overcome by demolishing it – and so, as science rose in the West, Christianity declined, until Nietzsche made his dramatic declaration that ‘God is dead.’

By reflecting on the heavens and the earth, another aspect of a Muslim scientist should come to the fore. The Holy Qur’an sates: ‘Those who remember Allah while standing, sitting, and lying on their sides, and ponder over the creation of the heavens and the earth: “Our Lord, Thou hast not created this in vain…”’[25] A believer reflects on the heavens and earth, and then says SubhanAllah (Holy is Allah). Whereas the present case of science can be summed up in the words of the Promised Messiah (as), who observed that every modern advancement has the net effect of taking humanity away from God, as each advancement was a means for humans to think that they are becoming god themselves.[26]

This is the difference between a Muslim scientist and a secular scientist: for every discovery a secular scientist makes, he says Subhan al-Rajul (Holy is Man) instead of SubhanAllah (Holy is Allah). And it is indeed this search for the beauty of God, reflected in His Creation, which should fuel the next evolution in science:

‘At this time of intellectual ignorance amongst the Islamic world, it is the great challenge for Ahmadi Muslim scientists and researchers to revive the honour and dignity of Islam in the global academic arena. Indeed, it should be your ambition to take up the glorious mantle of enlightenment adorned by the great Muslim scholars and inventors of the Middle Ages.’[27]

………………………………………………………

About the Author: Zafar Bhatti earned a Master’s degree in Physics from Imperial College London and has since gone on to build a career in the IT industry.

………………………………………………………

ENDNOTES

1. Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (rh), Revelation, Rationality, Knowledge and Truth (Tilford, Surrey: Islam International Publications Ltd., 1998), 94.

2. Sunan Ibn Majah, Hadith 4169.

3. Bihar al-Anwar, vol. 1, 177 & 180.

4. This is my own reading of history, more research is required on the Andalusian scientists.

5. Jeff Suzuki, Mathematics in Historical Context (Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America, 2009), 173.

6. Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (rh), Revelation, Rationality, Knowledge and Truth (Tilford, Surrey: Islam International Publications Ltd., 1998), 586-592.

7. The Holy Qur’an, 81:1-22.

8. Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 482.

9. The Principia is the great work of Isaac Newton which details the Law of universal gravitation.

10. Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 483.

11. The Holy Qur’an, 81:12.

12. The Holy Qur’an, 81:16-17.

13. The Holy Qur’an, 81:18.

14. The Holy Qur’an, 81:19.

15. This quote is taken from the famous English poet Alexander Pope.

16. The Holy Qur’an, 81:20.

17. Isaac Newton and Robert Hooke, Isaac Newton Letter to Robert Hooke, 1675.

18. Abu Hamid Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Ghazali, Incoherence of the Philosophers, trans. Sabih A. Kamali (Lahore, Pakistan: Pakistan Philosophical Congress, 1963), 2.

19. Ibid., 4.

20. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (as), Karamat al-Sadiqin, 103.

21. The Holy Qur’an, 41:13.

22. The Holy Qur’an, 51:48.

23. Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (rh), Revelation, Rationality, Knowledge and Truth (Tilford, Surrey: Islam International Publications Ltd., 1998), 309.

24. The Holy Qur’an, 27:89.

25. The Holy Qur’an, 3:192.

26. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (as), Noah’s Ark (Farnham, Surrey: Islam International Publications Ltd., 2018), 36.

27. Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad (aba), AMRA Conference 2019. Taken from https://www.pressahmadiyya.com/press-releases/2019/12/head-ahmadiyya-muslim-community-delivers-keynote-address-first-international-ahmadiyya-muslim-research-association-conference/

Add Comment