An Unlikely Friendship and a Journey to the Heart of the Qur’an

Carla Power (2015) – Holt Paperbacks

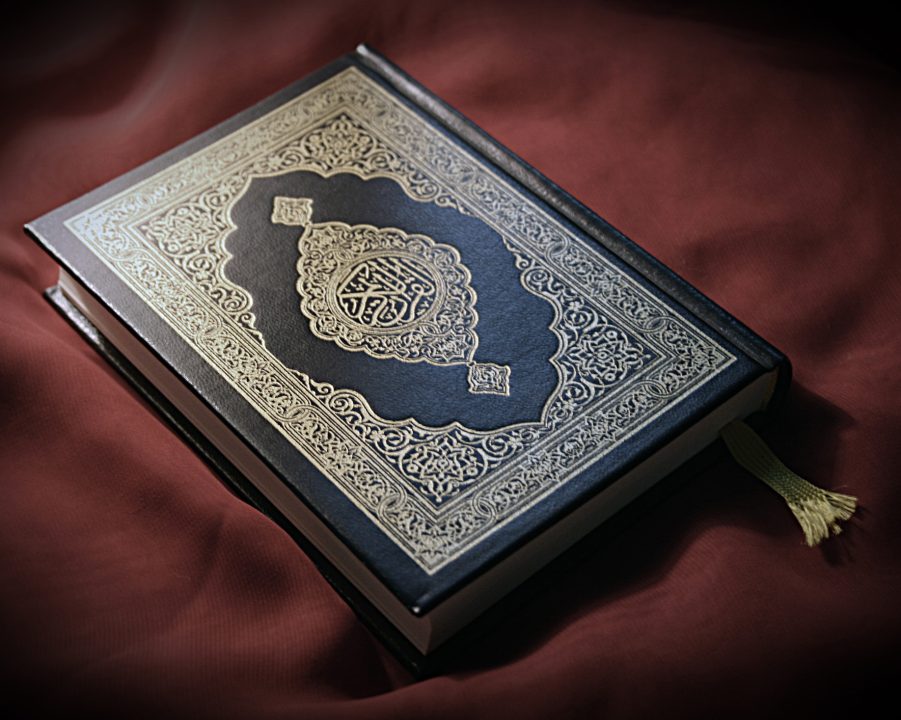

Carla Power’s exploration of Islam, entitled If the Oceans were Ink, references verse 110 from chapter 18 of the Holy Qur’an: ‘And if all the trees that are in the earth were pens, and the ocean were ink, with seven oceans swelling it thereafter, the words of Allah would not be exhausted. Surely, Allah is Mighty, Wise.’

If the Oceans were Ink was written as Power attempts to really understand those words of Allah which have been preserved in the Holy Qur’an. Having grown up with itinerant parents who would spend semesters teaching in predominately Muslim countries such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran and Egypt, Power grew up comfortable in and familiar with Muslims in general. And in her career as a journalist, she found herself reporting on ‘mosque design and yuppie Muslims, headscarves and punk bands, Islamic hedge funds and halal energy drinks,’ along with the required foray into bin Laden and the Taliban, extremism and atrocities.

And yet: ‘Never, in my seventeen years of writing magazine stories on the Islamic world, had an editor asked me to write about, or even cite, the Quran, and how Muslims understand it.’

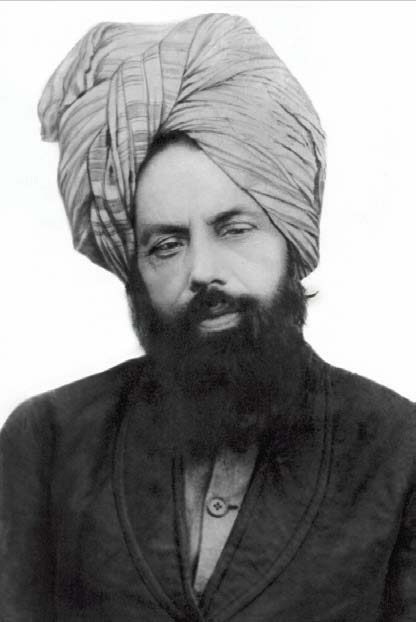

In order to remedy this lack of knowledge, Power reaches out to an old friend – Sheikh Mohammad Akram Nadwi, a graduate from a well-known madrasa in Lucknow, India, by the name of Nadwat al-Ulama. The two met in the early 90s at the Oxford’s Centre for Islamic Studies, where they worked on a research project which mapped out how Islam had spread throughout Southwest Asia.

Power explains how essential it is that the Qur’an be understood by both Muslims and non-Muslims:

‘Since Muslims consider it the word of God, a Quran not only offers comfort and inspiration as a text, but commands reverence as an object. This power has also led to the text’s politicization. Waved before a crowd, it can inspire revolutions and wars. Burned or besmirched, it triggers diplomatic incidents and deaths. Quoted or misquoted, it’s been used to justify mercy, and mass murder’.

In the year that follows, Power attends weekly sessions with Nadwi, discussing all of the topics that those in the West might struggle with – veiling, jihad, polygamy, and homosexuality – while also going deeper into issues such as prayer, Hajj and Umra (a pilgrimage to Makkah, similar to Hajj, but which is optional and can be undertaken at any time of the year).

But Power doesn’t just discuss these issues with Nadwi himself. Rather, the book is full of fascinating conversations she has with his daughters – bred in the UK, intelligent and accomplished in their own right – about wearing the niqab (the Islamic face veil which only allows a slit for the eyes to show) and women’s education. She interviews two of the advanced female students from his classes, who challenge the Sheikh – successfully – on the Islamic stance on child marriage. And she makes the long journey to India, to Jamdahan, the village where the Sheikh grew up, to experience first-hand the complicated interplay between Islam and local cultures.

And as Power delves deep into Qur’anic scripture, she learns that Islam defies neat attempts of characterisation, that one can be both deeply religious and fully progressive, with a progressivism arising from a strict fundamentalism.

Take the first example: Nadwi, having studied the Qur’an over and over again, realizes that his aunts have been cheated out of their inheritance, because the village custom was to not allow women to inherit land from their fathers. He goes back to his father and uncle, explains the Islamic teaching on inheritance, and restores to the women their birthright. This comes about not from a new progressivism, but an approach that reflects the fundamentals.

Similarly, Nadwi, closely reading the Hadith (oral traditions of the Holy Prophetsa), realises that many have been transmitted by women. Researching further, he finds not just 20-30 female Islamic scholars, but over 8000, upending narratives from both within Islam and without about women’s place in Islamic scholarship, and leading him to pen a 40-volume – and as yet unpublished – magnum opus on these overlooked yet important women.

In addition, Sheikh Akram Nadwi emphasises to Power over and over again the central importance of taqwa (translated by Power as love and awe of God). Power writes, quoting the Sheikh, ‘When people come far away from the purity of the religion, the outer aspects of the religion become identity’ and again and again, she comes back to the spiritual aspects of the religion.

Indeed, several chapters deal with the relationship between Islam and political power. Indeed, Power’s study of the Holy Qur’an was partly motivated by trying to understand (mis)interpretations of jihad. She quotes the Sheikh: ‘People think they can use Islam to fight for land or honour or respect or money. But these are not religious people.’ And they discuss the current quest for an Islamic state; as the Sheikh points out, secular governments allow Muslims to practice and worship as they please, so why do they yearn for a politically Islamic state?

This moderation can also be seen when they discuss the issue of the insults levied against the Holy Prophetsa. The Sheikh believes that Muslims should not issue fatwas or burn books in protest against those who defame the character of the Holy Prophetsa . Instead they should pray and invite them to the true teachings of Islam.

With Nadwi as her guide, Power takes the reader on an expansive journey. Her own open-mindedness, curiosity and flexibility of mind and her willingness to question not only the Sheikh’s worldview but her own, engages the reader and brings fresh insights to both Muslim and non-Muslim readers alike.

Add Comment