© Shutterstock

Unveiling the secret world beneath our feet, where fungi work their silent wonders.

Musa Sattar, London, UK – Deputy Science Editor

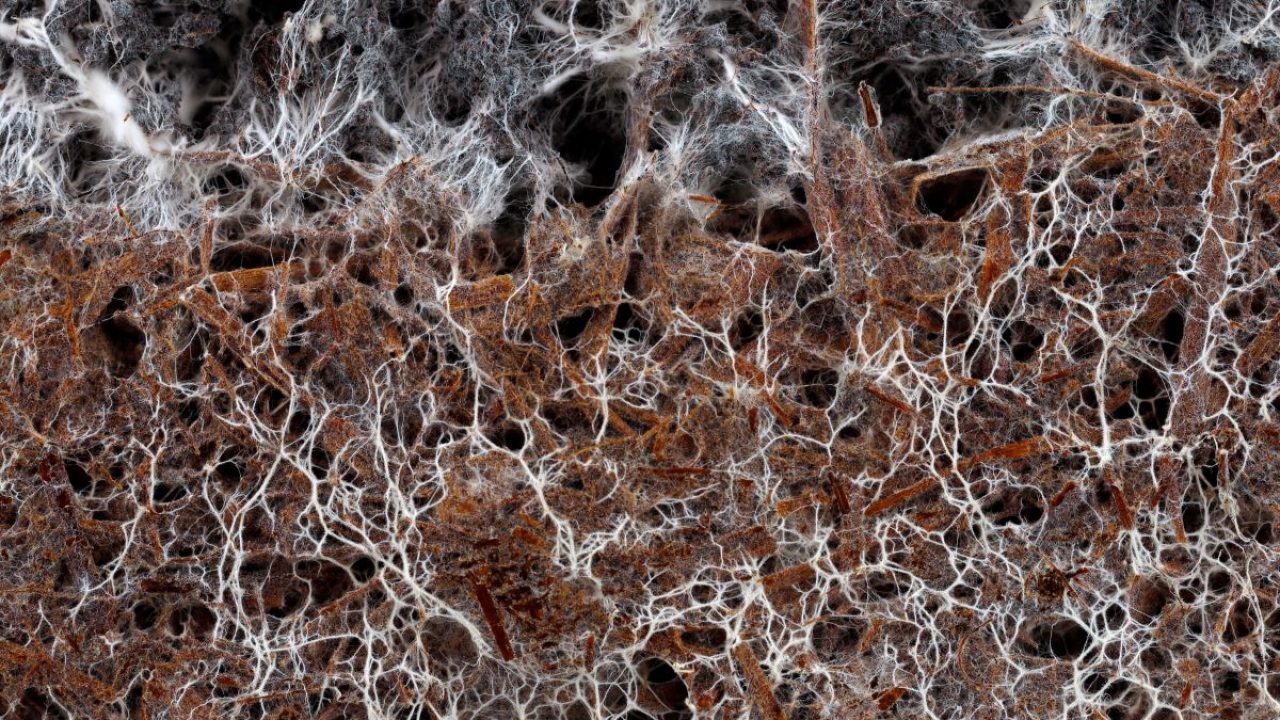

Imagine a bustling forest, where trees stand tall and proud, their roots delving deep into the earth. Yet, beneath the surface, a remarkable story unfolds. There’s a hidden network, almost like a secret internet, connecting everything in the forest. This invisible web isn’t made of wires or signals, but of tiny threads of fungal filaments called hyphae and their network is known as mycelium.

Mycelium creates sophisticated structures invisible to the human eye. This complex network, often overlooked in its significance, acts as nature’s silent conductor, weaving connections and nurturing ecosystems in ways that mesmerise even the sharpest scientific minds. Renowned mycologist Paul Stamets coined it the ‘Earth’s natural internet,’ highlighting the nature of its interconnectedness.

These fungi act as nature’s ultimate connectors, linking the roots of different trees and plants. Hyphae are found deep down in the soil, some wrapping around the roots of trees and other vegetation to form a mycorrhizal network. Interestingly, mycorrhizal networks can be so big that a kilogram of soil might contain 200 kilometres of hyphae.

Surprisingly, over 90 percent of land plants rely on a symbiotic partnership with mycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhizal symbiosis plays an important role in ecosystems because mycorrhizae affect plant productivity and plant diversity.

They act as nature’s delivery service, transporting nutrients and information from one plant to another. It means the plant can better absorb water and essential minerals such as phosphorus, zinc, manganese and copper. Moreover, the network helps the plants take up nitrogen from the soil.

It’s as if they’re whispering secrets and trading goods between the trees, ensuring that each one has what it needs to thrive. What’s fascinating is that a lone fungal network can link numerous trees, sparking curiosity about how it effectively distributes nutrients among them.

Even more remarkably, as Professor Suzanne Simard of the University of British Columbia has discovered, the mycorrhizal network also enables neighbouring plants to communicate with each other.

Most fungi grow as a network of thin tubes called hyphae that have a diameter typically ranging from 1 to 10 micrometers, with a few exceptions. When a spore lands on a good spot, it breaks open, and the first hyphae come out, stretching like long fingers into the spot. These hyphal tips release enzymes that break down the spot into tiny bits that the hyphae can soak up. These bits help the hyphae grow more and branch out, forming a dense mycelium. The hyphae on the edge of this mycelium move into new spots, looking for food. Meanwhile, the ones inside branch out a lot to feed on the food found.

Interestingly, mycelia (the branching structures of certain fungi), when they encounter obstacles in the soil, divide and explore to efficiently navigate around these barriers showing remarkable problem-solving abilities.

In fact, in just the top 10cm of soil, the fungal mycelium spans a mind-boggling 450 quadrillion kilometres. That’s roughly half the width of our galaxy. This is why it is commonly known as the ‘Wood Wide Web’. Studies suggest that while oceans store most of the planet’s carbon, a staggering three-quarters of terrestrial carbon is found in soil – three times the amount present in all living plants and animals combined. Thus, the fungal network in the soil thus helps regulate carbon cycles.

But the work of these fungal networks doesn’t stop there. When leaves fall and decay, these fungi come to the rescue, breaking them down into vital nutrients that nourish the soil. They’re the forest’s very own recyclers, making sure that nothing goes to waste.

Here’s the cool part: using a smart technique called allelopathy, trees send messages through these fungal networks to warn their neighbours about trouble or even stop invasive plants from taking over. And guess what? The neighbouring trees respond by releasing special chemicals or hormones to protect themselves, like a forest’s own defence squad! They even pass stress signals to nearby trees after big disturbances, like deforestation. They pick up the signs of ill health in their neighbour and send more nutrients its way.

This cycle of life, death, and rebirth keeps the forest thriving, with the fungi playing a vital role in every step. Although these fungal networks underpin life on Earth, they are largely unexplored. As Mark Tercek, former CEO of the Nature Conservancy, and a member of the governing body for the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN) describes, ‘If trees are the “lungs” of the planet, fungal networks are the “circulatory systems”.

Beyond the trees, the fungal network spreads its influence far and wide, creating a harmonious ecosystem where every piece has a role to play. It’s a testament that even the smallest organisms are part of something greater, working together to keep the forest alive and thriving. Merlin Sheldrake, a biologist and author of Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures, describes fungal networks as often hidden and overlooked but vital contributors to life on our planet.

Now, pause and reflect on the extraordinary phenomena of nature. Is it possible that such vast and intricate networks came into existence haphazardly? Or is there a guiding hand behind this invisible magic? Could it be that there exists a guiding force, an unseen maestro directing this flawless performance? A force that paints the forest floor with the brushstrokes of unity, ensuring that no element, no life form, is ever truly alone? As we delve deeper into the complex world beneath our feet, we can’t help but ponder the enigmatic Creator behind this masterful composition.

So, as we walk through the woods, let’s remember the incredible work happening beneath us, the silent magic that keeps the forest in balance. Let’s marvel at the wonder of nature’s hidden connections and contemplate the mysteries of the forest floor, where fungi reign supreme in their quiet, yet essential, role.

Further Reading:

https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0033-2017

Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World (Ten Speed Press, 2011).

Merlin Sheldrake, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures (Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2021).

Add Comment