Unmasking the quiet terror of nuclear physics, where invisible forces shape irreversible outcomes

Musa Sattar, UK

A recent military strike damaged an above‑ground section of Iran’s Natanz fuel‑enrichment plant. International Atomic Energy Agency Director‑General Rafael Grossi told the U.N. Security Council that the attack left ‘radiological and chemical contamination’ within the facility. Fortunately, monitoring shows no external release posing no immediate public danger thus far. Nonetheless, even a minor breach highlights the serious potential for harm to both people and the environment extending beyond the targeted State’s borders. Meanwhile, the threat of nuclear war over Ukraine looms larger with each passing week, casting a long shadow over international diplomacy.

This fragile geopolitical landscape reminds of many warnings voiced by His Holiness Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad (aba), Fifth Caliph and Worldwide Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. For instance, in 2019, during his landmark address in Berlin titled ‘Islam and Europe: A Clash of Civilisations?’, he cautioned:

‘Reminiscent of the dark days of the past, opposing blocs and alliances are forming and it seems as though the world is hell-bent on inviting its destruction…All it takes is one miscalculation or misstep for hostilities to trigger the unthinkable. The consequences of such a war are incomprehensible but it is safe to say that the world will never be the same again.’

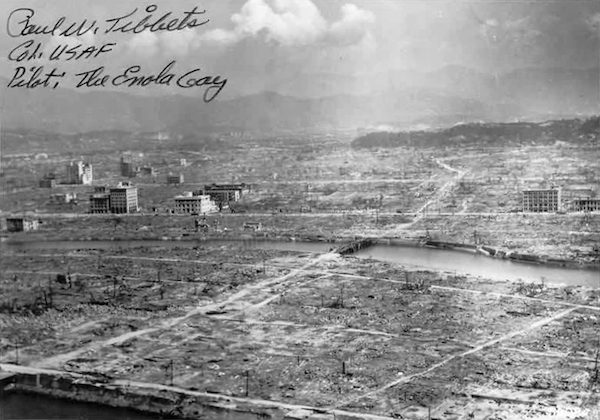

In 1946, American journalist, John Hersey travelled to Hiroshima for The New Yorker unveiling Hiroshima’s aftermath and forced the world to confront a new kind of horror, one that burned through the skin and settled deep in memory. Capturing a pain too deep for words, he described survivors whose faces were wholly burned, their eyesockets were hollow, the fluid from their melted eyes had run down their cheeks. It was a vision so haunting that Hersey admitted, ‘It would be impossible to say what horrors were embedded in the minds of the children who lived through the day of the bombing in Hiroshima.’

Mitsugi Moriguchi, a hibakusha (Japanese term for the surviving victims of the atomic bombs which fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki) who was just nine years old when the bomb fell on Nagasaki, gave voice to this enduring anguish in a 2019 interview titled Voices from Japan. His words are heartbreaking: ‘The effect of the atomic bomb, you know, still is lasting even today. The atomic bomb itself is an inhumane weapon.… But I wonder if it is allowed to use any type or any kind of bomb just to stop the war. Even babies, children, dogs and cats, and old people all died. I think that we cannot allow, we are not allowed, to make more such weapons.’

Whether or not humanity can steer away from this abyss may well be the greatest test of our collective wisdom. But the signs, frankly, aren’t reassuring.

This is the realm of nuclear detonation physics where a complex and terrifying energy unleashed in mere seconds. While history remembers the mushroom clouds, the ruined cities, and the scarred survivors, the forces that make it all happen remain hidden in plain sight. To understand these forces is to understand the stakes of the modern age.

Let us explore the very core of this explosion and map the invisible world that emerges when humans split the atom.

The Unfolding of a Detonation

When a nuclear bomb detonates, the energy released does not simply explode outward in all directions, it divides. Roughly 50 to 60 percent becomes a blast wave, a thunderous compression of air that levels buildings and sends debris careening through the sky. Another 35 to 45 percent transforms into thermal radiation; searing heat that can ignite clothing and trees, and char human skin miles away. The remaining 5 percent is prompt ionising radiation: gamma rays and neutrons that streak out like invisible needles, poisoning cells before a person even knows they’ve been touched.

But this isn’t the whole picture. There is a final, sinister act: radioactive fallout. While the blast and fire pass in seconds, fallout lingers, drifting silently with the wind, infiltrating soil, crops, and lungs. This is the ghost of the bomb, the aftermath that can shadow a landscape for generations.

The Physics of Blast Waves

At its core, a blast wave is air displaced with such violence that it acts like a wall of force. The physics behind it is deceptively simple: as energy from the detonation forces its way outward, it compresses the air ahead of it, creating a high-pressure front that radiates outward at supersonic speeds.

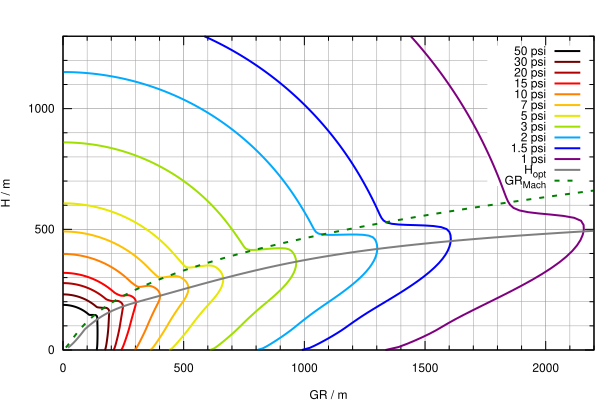

A higher detonation altitude maximises blast and thermal coverage but reduces fallout. A lower altitude or surface detonation concentrates radiation and fallout but limits blast range.

In 1946, Operation Crossroads Able demonstrated this power when a 23-kiloton airburst missed its target by over 600 metres but still caused significant damage due to the nature of hemispherical blast propagation.

Then there was the Tsar Bomba, the Soviet Union’s 50-megaton behemoth. Its explosion in 1961 created a 500-mile-wide zone of destruction; an unearthly testament to the nonlinear scaling of blast energy. The blast sent a mushroom cloud soaring 45 miles high, brushing space and stretching 60 miles wide.

Eyewitnesses to the nuclear blast described it with haunting clarity, ‘like a funnel, the whole earth seemed to be drawn in’ and ‘as if the Earth was killed.’ As documented in the National WWII Museum in New Orleans, the explosion didn’t just rupture the sky; it shook the very soul of those who watched.

Thermal Radiation and Burn Radius

Thermal radiation, often underestimated, is the fire-starter of the nuclear event. It ignites wood, melts asphalt, and burns skin in an instant. This radiant heat obeys an inverse square scaling law: a hundredfold increase in yield only stretches the burn radius by about six times.

In Hiroshima and Nagasaki, this phenomenon painted a cruel mural of evidence; clothing patterns burned into skin, shadows etched into stone, fires erupting miles across the cityscape. The firestorm in Hiroshima reduced 8 square miles (an area larger than Central London) to scorched ruins. In Nagasaki, the inferno swallowed 4.2 square miles, leaving behind a shattered, smoldering wasteland.

The temperature at the epicenter soared to over one million degrees centigrade. Urban terrain, with its glass, concrete, and tar, exacerbates thermal effects, turning streets into furnaces and buildings into kindling.

The Aftermath in the Wind

Prompt ionising radiation, gamma rays and neutrons, moves invisibly but lethally through the air in the first few seconds of detonation. A nuclear explosion causes extreme heat, powerful shockwaves, and radioactive fallout. This fallout spreads particles that contaminate the ground, water, and air with lasting effects for decades. Ground zero (the area near the blast) becomes a ghost zone, scorched by radiation and stripped of life, its scars etched deep into the planet’s skin.

Fallout is not a force that strikes and leaves. It is the nuclear detonation’s echo, composed of radioactive particles that form in the cooling fireball and are lofted high into the atmosphere. There, they hitch rides on wind currents, raining down in patterns dictated by the whims of the weather, the terrain below, and the height of the burst.

Ground bursts, detonations near or at the surface, suck up earth, building material, and anything else nearby, which then condense into radioactive dust. Airbursts, by contrast, tend to create less fallout but more immediate devastation.

At Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, researchers are moving beyond empirical models of fallout to microphysical simulations. Helping us map not only where fallout will go, but how dangerous it will be when it gets there.

NUKEMAP an interactive simulation tool allows users to model a detonation over any city. It offers a visceral view of damage zones: 20 psi overpressure rings that flatten concrete structures, thermal zones where third-degree burns are likely, and radioactive plumes trailing across maps like invisible scars. With it, the unimaginable becomes graspable. It shows us while atoms split in moments, the scars they leave on bodies, landscapes, and societies, linger for generations.

Forces that Can Rewrite History in Seconds

In the silence after a nuclear blast, if there is anyone left to hear, it is not just buildings that have vanished.

It is the illusion of control.

In a reflection captured by the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History, Dr. Michihiko Hachiya, a medical doctor who survived the bombing, recalled: ‘Nothing remained except a few buildings of reinforced concrete… For acres and acres the city was like a desert except for scattered piles of brick and roof tile.’ He struggled to convey what lay before him: ‘I had to revise my meaning of the word destruction or choose some other word to describe what I saw. Devastation may be a better word, but really, I know of no word or words to describe the view.’ His account is a haunting reminder that the physics of nuclear detonation doesn’t just level structures; it defies language itself.

Some survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki incident disoriented by the scale and nature of the destruction, believed they had not survived at all. With no point of reference for the bomb’s absolute devastation, many thought they had crossed into a netherworld where the boundaries between life and death had dissolved.

According to records from the Atomic Heritage Foundation, the sensation was so surreal that it felt spiritual or apocalyptic. A Protestant minister later recalled, ‘The feeling I had was that everyone was dead. The whole city was destroyed… I thought this was the end of Hiroshima – of Japan – of humankind… This was God’s judgment on man.’

Among the many harrowing eyewitness accounts of Nagasaki, Tatsuichiro Akizuki, a physician and survivor, described a scene so surreal it seemed torn from the fabric of nightmares. ‘It seemed as if the earth itself emitted fire and smoke,’ he recalled, ‘flames that writhed up and erupted from underground. The sky was dark, the ground was scarlet, and in between hung clouds of yellowish smoke. Three kinds of color -black, yellow, and scarlet – loomed ominously over the people, who ran about like so many ants seeking to escape… It seemed like the end of the world.’ His words paint the kind of sensory horror no physics equation can quantify, a landscape disfigured beyond recognition, suspended between combustion and silence.

By revealing the laws behind the chaos, by turning fireballs into formulas, and ash into datasets, physics doesn’t strip away the horror. It translates it.

We are no longer living in an age of ignorance. Today the mushroom cloud is not mystery but quantifiable data of equations, wind charts and casualty model s offering us insight into the grave consequences.

The Overlooked Solution

The world today stands precariously on the edge of disaster. With growing tensions between nuclear powers, the potential for conflict casts a long, chilling shadow. The science of nuclear detonation shows us the immediate horror; the blast, the fire, the radiation but it also warns of something slower, more insidious: the prolonged, paralysing aftermath that war would leave behind. Even if humanity somehow limps through a nuclear war, what kind of life would remain? A fractured world, biologically and morally scarred, where generations would pay the price for a moment’s miscalculation.

So, what then is the path forward? How can we shield the world, not only from nuclear fire, but from the slow moral decay that follows in its wake?

His Holiness, Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad (aba) has offered a profound yet overlooked solution. Again and again, he has urged mankind toward a different course, one not built on arsenals or alliances, but on humility and justice.

He reminded,

‘there is only one solution to help the situation of the world return to normal and that is for mankind to turn to Allah the Exalted and to fulfil His rights and the rights of His creation.’

On another occasion he said,

‘At this critical moment in history, I believe with all my heart that there is only one way to bring an end to the great challenges of our time. There is only one path that can lead us to salvation and deliver us from this world of war and conflict and that is the path of God Almighty. Peace does not lie in power or wealth, rather peace lies in the cradle of God Almighty.’

The choice, ultimately, rests with us, especially with world leaders. Will they heed this call to conscience and choose the path of peace? Or will they continue to gamble with a fire no one can control? The clock ticks on, but the answer has always been in our hands.

About the Author: Musa Sattar has an MSc in Pharmaceutical Analysis from Kingston University and is also serving as the Assistant Manager of The Review of Religions and the Deputy Editor of the Science & Religion section.

Further Reading:

P. Andrew Karam, Radiological and Nuclear Terrorism: Their Science, Effects, Prevention, and Recovery, (Springer; 2021).

Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, (Simon & Schuster; 2012).

Committee on the Effects of Nuclear Earth-Penetrator and Other Weapons, Effects of Nuclear Earth-Penetrator and Other Weapons, (National Academies Press; 2005).

Comment Title: Mapping Moral Fallout Alongside Physical Forces

The above article was a great informative read. It not only clarified the physics behind nuclear detonation and fallout, but also prompted deeper reflection on the moral and spiritual consequences of such forces. This article compellingly reveals the invisible physics behind nuclear detonation and fallout—but there’s another layer of unseen force: the moral and spiritual consequences of humanity’s choices.

As the SIPRI Yearbook 2025 warns, “Nearly all of the nine nuclear-armed states… continued intensive nuclear modernization programmes in 2024… Around 2100 of the deployed warheads were kept in a state of high operational alert on ballistic missiles” (SIPRI.org). These figures are not just technical—they represent decisions that shape generations.

Recent conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza, Kashmir, and Iran remind us how fragile peace remains. While leaders negotiate behind closed doors, ordinary people are left with one enduring power: prayer.

“O our Lord, pour forth steadfastness upon us, and make our steps firm, and help us against the disbelieving people” (Al-Baqarah, 2:251).

Khalifatul Masih V (aba) reminded us in 2018:

“It is only the Grace of Allah the Almighty that can save the world from destruction… Simply believing in the Promised Messiah (‘Alaih-is-Salām) is not enough… it places an even greater responsibility to fashion our lives according to the pleasure of God Almighty” (alislam.org).

And in 2012, Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad (aba) warned:

“When God Almighty is forced to take action, then His Wrath seizes mankind in a truly severe and terrifying manner… The weapons available today… could lead to generation after generation of children being born with severe genetic or physical defects” (Ahmad, 2012).

The fallout may be invisible, but its moral weight is undeniable. We must act—spiritually and civically—to urge our leaders toward peace, not escalation, and justice, not destruction.

“The decree of Allah is coming, so seek ye not to hasten it. Holy is He, and exalted above all that which they associate with Him” (An-Nahl, 16:2).