© Shutterstock

Musa Sattar, London, UK, reporting from Guatemala.

It is a bright Friday morning at the Baitul Awal Mosque in Guatemala City. The call to prayer is still an hour away, and the library next to the prayer hall is quiet except for the low hum of the air coming from the windows and the muted rustle of pages. I am seated at a wooden table with my laptop, working on some routine work before the Friday sermon. Beside me sits my father, Imam Abdul Sattar Khan, who only recently returned from Costa Rica.

The door opens, and a woman steps inside with two young children. She wears a light brown coat over a modest dress and a soft headscarf. Her children drift towards the low shelves lined with Spanish and Arabic books. When she notices my father, her face lights up with unmistakable relief. ‘Imam,’ she says in Spanish-accented English, ‘Alhamdulillah (all praise belongs to Allah), you are well!’ They greet each other warmly. My father, smiling, introduces her to me as Fatima, once known as Veronica.

As we sit together in the library’s gentle quiet, she begins to tell me how she became an Ahmadi Muslim and why she respects my father so deeply. ‘He taught me,’ she says, ‘like a father teaches his child.’ Intrigued by her identity from Veronica to Fatima, I sat down to listen to her story.

‘I was outside my house in San Marcos,’ she recalls. ‘It was night. The moon was full. In my dream, everything was the same but different. It was also night time. It felt very chaotic; people were running everywhere. And I see them and I say, “Oh my God, it’s the end of the world.” At that time, the sky opened and a man came down. I looked at him and said, “If I have ever done anything wrong, give me a chance. Give me the opportunity to apologise to everyone.” He called me Fatima. He held out his hand. I said, “I’m not Fatima, I’m Veronica.” But he smiled and said, “No, you are Fatima. Come, I will show you the truth.”’

She paused for a moment with tears in her eyes. ‘This is why I am Fatima now,’ she continued.

San Marcos, her hometown, sits high in the western highlands of Guatemala, about five and a half hours from the capital, Guatemala City. The town’s winding streets lined with whitewashed churches and small plazas reveal its traditional face. Yet beneath this picturesque setting lies a history shaped by rebellion, drug trafficking, and an undying passion for football. Despite these turbulent undercurrents, Catholic processions still anchor the town’s calendar, weaving devotion into everyday life. Fatima grew up deeply woven into this fabric, and her family and friends saw her as devout and reliable.

In San Marcos, Islam was almost unheard of. Yet the dream unsettled her. She explains how, in that dream, she saw Makkah and Madinah, how she was given a book she could not read but somehow could recite. ‘Then I took his hand and suddenly we were on a bus. He pointed and said, “Look, this is Makkah.” I saw people, statues, and the place where Islam began. Then we flew to another place and he told me, “This is Madinah.” I witnessed an amazing story unfolding, how Islam was growing despite so many problems, and how people resisted it. In my dream, I had no idea what Islam was or why I was seeing all this, but it felt so real. After showing me Makkah and Madinah, he took me to a mountain. He gave me a book, opened it and said, “Recite.” I looked at the pages and said, “I don’t understand, I can’t read these lines.” But he reassured me, “You can do it,” and he taught me with such incredible calm and peace. Even now, when I remember that dream, I get goosebumps. I began to recite. My mind did not understand the words, but my heart and soul knew them. Alhamdulillah. And then I woke up.’

‘I felt peace everywhere,’ she says, her eyes closing briefly. ‘When I woke up, I was crying.’

When she told her ex-husband, an American, about the dream, he dismissed it sharply. He warned her that Islam was dangerous and despised. ‘My ex-husband looked at me and said, “Do you even know what Islam means?” I told him honestly, “No, I don’t. I’m only telling you my dream.” He shook his head and said, “Islam is the religion of Muslims. They’re not good people. They’re terrorists.” Hearing that broke my heart because what I had felt in my dream was only peace. He told me Muslims were terrorists, that women were under their feet,’ she says, her voice tightening. ‘He could not understand why I felt peace in that dream.’

Born and raised in a devout Catholic family, Fatima lived a disciplined religious life. She attended mass daily, joined extended prayer sessions at her parish and sought to embody the values of her church. ‘They have a special time for praying. They call this special time “special hour”, where people came and prayed for two hours and stayed there in the church. I was one of those people.’

Which is why her dream startled everyone she told. Her parents wondered if it had been Jesus Christ appearing to her. Her mother advised her to go to church and ask the priest why she had that dream.

‘I had always respected our priest. He guided the people of our church, so I trusted him. I went to him and said, “Father, I had this dream. It gave me such peace. Can you help me understand it?” He frowned and said, “This is very bad,” then used words so foul I can hardly repeat them. In my heart, I thought, “How can he speak like this about other people? All people are God’s creation.” I asked him, “Why do you say such things when my dream gave me peace? I truly want to understand. What is Islam?” He shook his head and said, “Islam is the worst. Muslims kill. They are cruel, maldito (damned).” Hearing that broke my heart and confused my mind even more.’

Fatima told me that weeks went by, but the dream would not leave her. It pressed on her heart and disturbed her sleep. ‘I needed to understand this. I needed to find its meaning,’ she remembered. ‘But nobody could give me a clear answer.’

At the time, she was working as a teacher in San Marcos. One day, she confided in the school principal about her dream. The principal listened and then suggested, ‘You know, my daughter is a Protestant minister. She is very good at interpreting dreams. You should go to her. She will give you the answer.’

Fatima agreed. ‘I said, “Okay, thank you,”’ she recalled, and soon visited the church where the daughter preached. The minister welcomed her kindly, listened to the dream in full and then said softly, ‘These people are not good. They are terrorists.’

‘She used polite words,’ Fatima said, ‘but the message was the same.’ As she left the church, she felt a rising confusion. ‘Why does my dream not match what they are saying?’ she wondered. ‘My dream gave me peace, not fear.’

RoR Photos

The Baitul Awal Mosque in Mixco, Guatemala, where Fatima continued her journey of learning moreabout Islam, and entered the fold of Ahmadiyyat.

Fatima told me that after exhausting her local contacts, she turned to her American mother-in-law for guidance. She recounted the dream and confessed her confusion.

‘I told her, “I don’t understand why everyone talks badly about Islam. My dream gave me peace,”’ Fatima recalled. Her mother-in-law looked at her seriously. ‘She told me, “It is true. Islam is not seen as good. Even in the States, if someone knows you follow the Islamic way, they will look at you with suspicion. But do not trust me. Go to Google. Read for yourself. Do not go to one site. Read many. You will find the truth.”’

Those words stayed with her. ‘So I did exactly what she said,’ she continued. ‘I went to Google. It opened many doors for me. Some were good, whilst others were negative. But then I found the good one. Alhamdulillah. I started reading and reading. I found my way. I found what I was searching for to complete my soul, my heart, my life.’

Her ex-husband, however, reacted angrily when he found her busy with her research. ‘He told me, “If you start following this religion, you are stupid. If you go to the States with this religion, they will not let you in. They will kick you out. The government hates Muslims. They are terrorists,”’ she said softly. ‘I looked at him and said, “Okay. This is what I want. I do not know why you think I want to go to the States. I do not need to go to the States. I am happy here. I am happy to learn and I will do it more.”’

Her relentless devotion to seeking the truth about Islam came at a painful cost. Unable to accept her journey, her husband walked away, leaving her alone to raise their children.

As she recounted this part of her story, her eyes filled with determination. The disapproval she faced only strengthened her resolve to search for the truth herself.

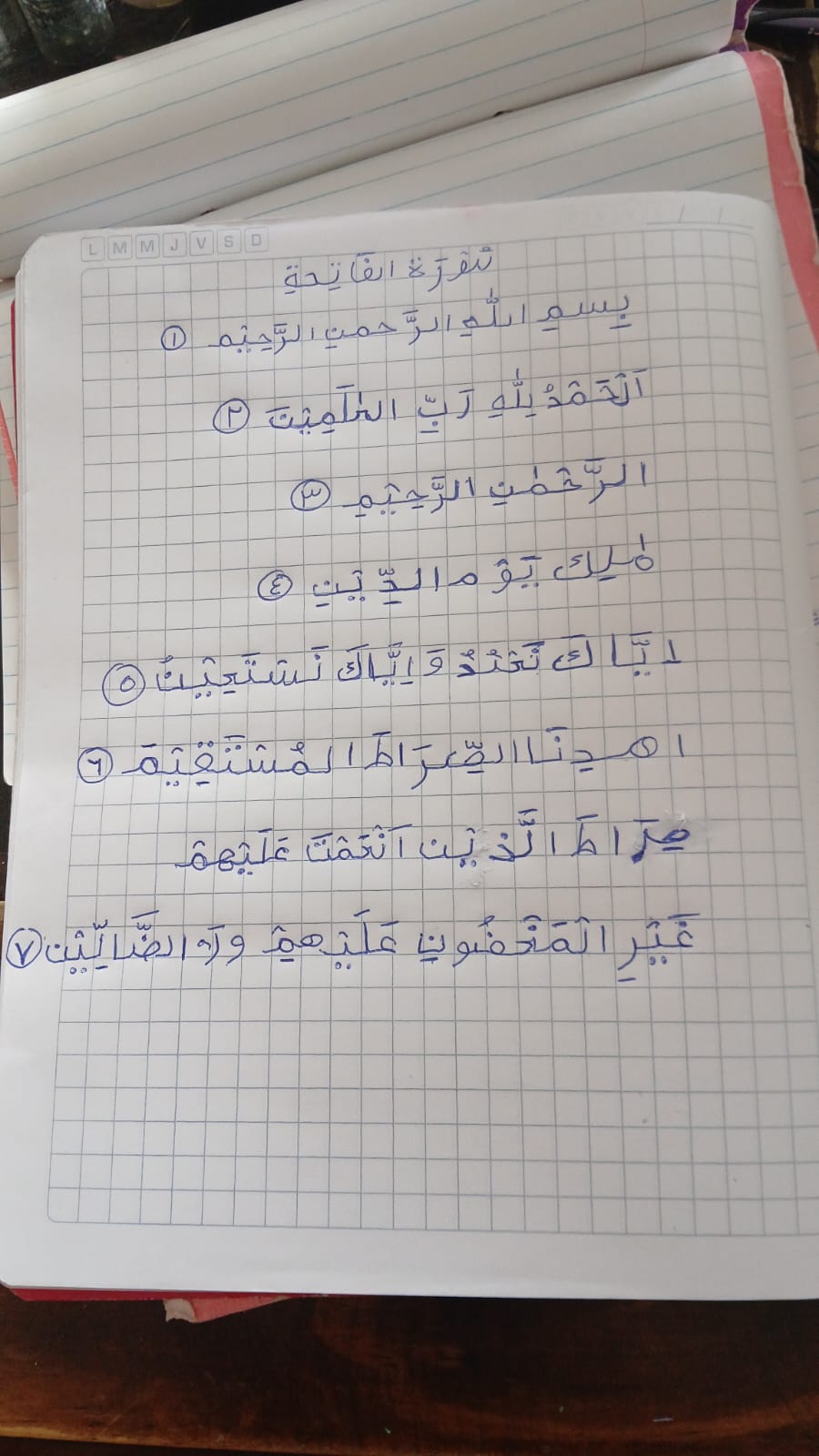

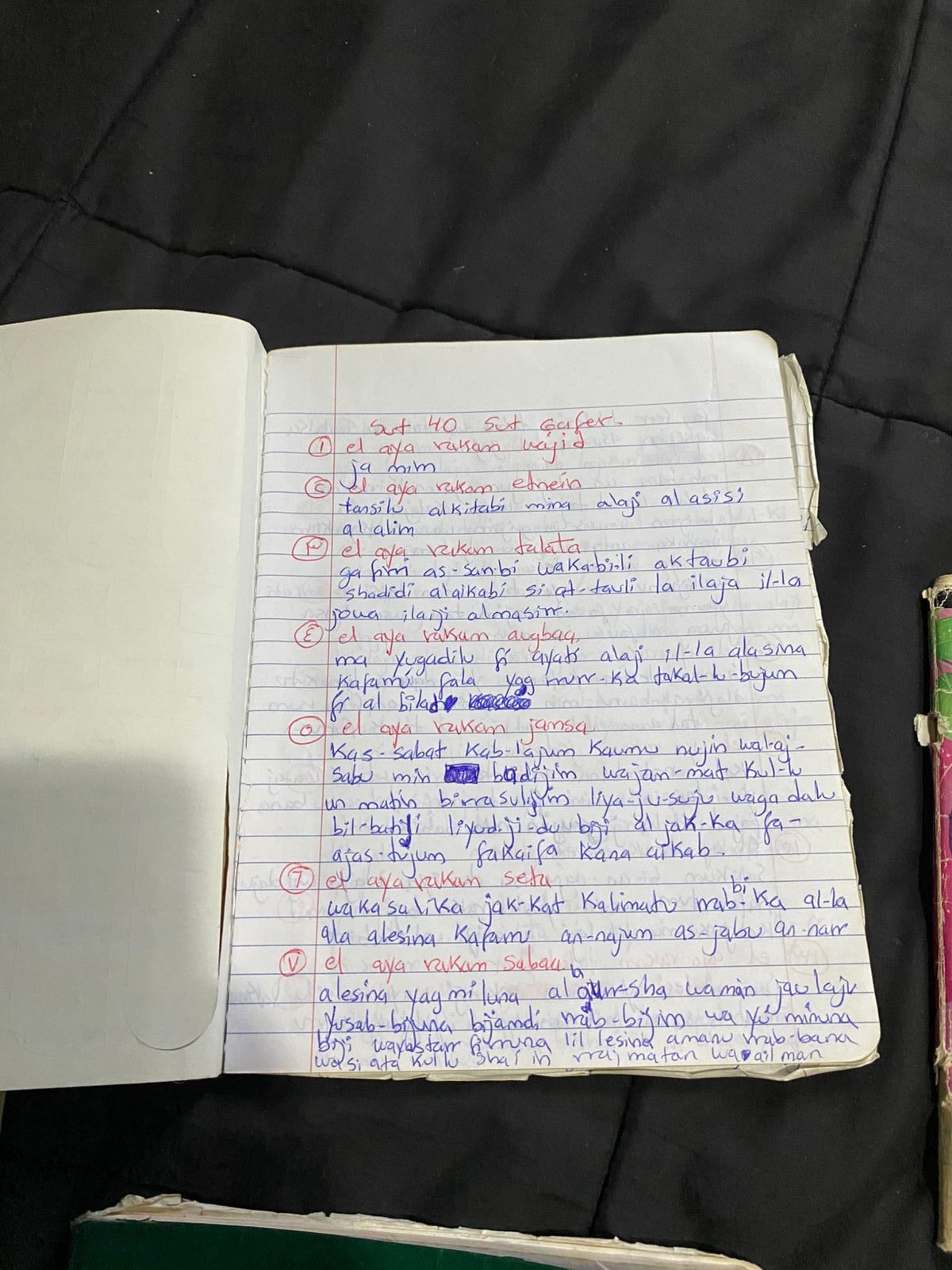

Fatima said the months after that conversation with her mother-in-law became a period of deep study and private devotion. Late at night, after her children had gone to bed, she sat at the kitchen table with her computer and notebooks. ‘I downloaded Qur’anic recitations,’ she explained. ‘I played a surah (chapter), stopped it, wrote it down, played again, listened, stopped and copied it again. That is how I wrote the complete Qur’an by hand in Arabic. Every single line.’ She smiled at the memory. ‘It took me months. When I finally finished, I cried with happiness. Alhamdulillah.’

With no teacher and no Muslim friends, she taught herself Arabic like a child starting school. ‘I learned the alphabet slowly. I practised reading like a second-grader,’ she said, laughing softly. ‘But it was beautiful. It felt like my heart was learning as much as my mind. In my heart, I had already accepted Islam.’

Eventually, she began to wonder whether there was a mosque anywhere in Guatemala. ‘I thought, there must be at least one,’ she told me. Searching online, she discovered the Baitul Awal Mosque of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in Guatemala City. She phoned repeatedly and was welcomed by the imam, but unfortunately, by then the COVID-19 pandemic had shut down public transport. ‘For a whole year I waited. I wanted so badly to go, but the buses were not running,’ she recalled.

When the restrictions were lifted, Fatima finally made the almost six-hour journey from San Marcos to Mixco, Guatemala City. ‘When I arrived at the mosque, I was shaking,’ she said. ‘I knew how to read, but I needed guidance. Imam Abdul Sattar helped me. He took time with me, taught me patiently, like a father teaches a child.’ She explained how he showed her how to improve her recitation and guided her through the fundamentals of Islamic practice.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Fatima wrote down the entire Qur’an in her notebooks, both in Arabic and in Spanish.

He also introduced her to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community and explained the different sects within Islam. ‘I had so many questions,’ she admitted. ‘Alhamdulillah, I found the answers here.’ Her eyes softened when she spoke about that time. ‘I respect him a lot. I did my bai’at (pledge of allegiance). He was part of my journey to Islam Ahmadiyyat.’ She paused, her eyes glistening as she turned toward my father, a look of deep respect and quiet love softening her face while tears gathered at the corners of her eyes.

Fatima’s commitment deepened. She started visiting the mosque whenever she could, sometimes bringing her children. Yet the long journey was exhausting. ‘I realised,’ she said, ‘that I wanted to be close to the mosque, to learn more, to live this life fully.’

So she moved her family to Antigua, a colonial city framed by three volcanoes and famous for its cobblestone streets. In a small rented home just about an hour away from the mosque, she began a new routine. ‘Now my children’s school books are next to my Arabic workbooks,’ she said with a small smile. ‘I rise before dawn to pray. I go to the mosque regularly. This is my life now, Alhamdulillah. Alhamdulillah, I know the path I am walking is real. It is no longer a dream. It is my life.’ she repeats. ‘Allah guided me.’

Her story is more than conversion. It is an act of intellectual courage and devotion. She crossed religious and cultural boundaries, challenged stereotypes in her community and built her own bridge to knowledge, writing out the Qur’an word by word.

As our conversation in the library ends, the call to prayer echoes from the mosque. Her children gather their books. Fatima rises, smiling. ‘I still dream sometimes of Makkah and Madinah,’ she says softly. ‘But now I know this path is real. It is my life.’

Add Comment