The Review of Religions is pleased to present the first part in a two-part article on the fascinating art and history behind Islamic calligraphy. 2nd part is available here now

Calligraphy is a fundamental element and one of the most highly regarded forms of Islamic Art.

The word calligraphy comes from the Greek words kallos, meaning beauty, and graphein, meaning writing. In the modern sense, calligraphy relates to “the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious and skilful manner.”1 Islamic calligraphy is one of the most sophisticated in the world and is a visual expression of the deepest reverence to the spiritual world.

The Holy Qur’an mentions, with regard to the revelation of the Holy Qur’an “And we have arranged it in the best form.”2![]()

In this verse, the phrase “in the best form,” indicates the putting together of parts to form a strong, integral, consistent whole. Therefore, the Arabic word tartil is translated as a reflective, measured and rhythmic recitation.3 The Islamic scholar Hafiz Fazle-Rabbi has elaborated that this word, when used in the context of writing, can refer to calligraphy, as a means of beautifying the writing.4

It is narrated by Hazrat Amir Muawiyara that the Holy Prophet Muhammadsa said, regarding the correct style of Qur’anic writing: “O Muawiya, keep the correct consistency of your ink under the inkpot, make a slanting cut to your pen, write the ‘Ba’ of Bismillah prominently, also sharply write the corners of the letter ‘Seen’, do not make an incorrect eye of the letter ‘Meem’, write the word Allah with great elegance, elongate the shape of the letter ‘Noon’ of the word Rahmaan, and write Raheem beautifully, and keep the pen at the back of your right ear so you will remember that.”5

The act of calligraphy is intriguing in that it leaves a tangible trace of a physical act. But that written trace does not merely record an action. In some Muslim areas, calligraphy was actually considered to leave clues as to the calligrapher’s moral fibre. Indeed, the quality of the calligraphy was believed to hold clues as to the character of the calligrapher. The tools used in calligraphy: the paper on which it was written, the writing implements, the gold leaf used in illumination—all required a diverse set of skills.6

Calligraphy holds, perhaps, pride of place as the foremost and most characteristic of the modes of visual expression in Islam. After years of practice, calligraphy becomes second nature to a master calligrapher. However, the dots always allow for a quick assessment as to whether or not the proportions are correct.

It is mentioned in Kanzul-Ummaal, (Treasure of the Doers of Good Deeds) as narrated by Saeed ibn-e-Sakina, that Hazrat Alira saw a person writing Bismillah and then said, “you have to write it in a beautiful manner, because if you do this, then Allah will bless and forgive you.”7

The great Egyptian writer, Taha Hussein, once said: “Others read in order to study, while we have to study in order to read.”8 His complaint was more than justified. The intricacies of calligraphy can take years to master.

In Praise of Calligraphy

Islamic calligraphy was not only acclaimed by the Muslim world, it was also considered a great artistic mode of visual expression.

Pablo Picasso was so inspired by Islamic calligraphy that he said: “If I had known there was such a thing as Islamic calligraphy, I would never have started to paint. I have strived to reach the highest levels of artistic mastery, but I found that Islamic calligraphy was there ages before I was.”9

Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple, started his creative career inspired by geometry and the art of calligraphy. In his biography it was mentioned that calligraphy workshops influenced Apple’s graceful, minimalist aesthetic. These experiences, Jobs said later, shaped his creative vision.10 Indeed, in his Stanford commencement address in June 2005, Jobs said: “If I had never dropped in on that single calligraphy course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts.”11

Martin Lings, also known as Abu Bakr Siraj ud-Din, was an English writer and scholar who also penned a biography of the Holy Prophetsa. His teaching has guided and inspired the Thesaurus Islamicus Foundation in all its work with the sacred arts of the Holy Qur’an. Lings believed that the pinnacle of Islamic art was Arabic calligraphy, which transmits the verses of the Holy Qur’an into visual form.12

Indeed, the history of Arabic calligraphy is inextricably linked with the history of Islam. There is also a close relationship historically between each Arabic script and its common usage. According to the history of written language, Arabic is only second to the Roman alphabet in terms of widespread usage today.13

a thing as Islamic calligraphy, I would never have started to paint. I have strived to reach the highest levels of artistic mastery, but I found that Islamic calligraphy was there ages before I was.” Paolo Monti | Wikpedia Commons | Released under Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

Pre-Islamic Arabs relied heavily upon oral traditions for the retention of information and for communication. Later, calligraphy became an invaluable tool for communication.

The Alphabet Family Tree

It is very hard to trace the origins of Arabic script, but there is evidence that it was very well-known to the Arabs in Arabia although they did not widely use the script and actually depended instead on verbal and oral traditions. It is believed that the recent Arabic Script was most likely developed from the Nabataean script, which was itself derived from the Aramaic script. It should be noted that all of these Semitic languages (Phoenician, Canaanic, Aramaic, Nabataean, etc.) were not more than slang versions of Arabic which had become separate languages with the passage of time due to limited communication with central Arabia. But Arabia preserved pure Arabic, especially in remote areas. The most interesting and mysterious phenomenon was that Arabic was an incredibly rich language, in stark contrast to the primitive Arabs who used it, indicating that they themselves did not create the Arabic language. This phenomenon supported the theory that the language was not man-made but actually a result of divine revelation. Arabia provided the perfect environment to preserve it because it was less influenced by external factors, unlike other parts of the world. While the Arabic language is very ancient, it was not known to be a written language until perhaps the third or fourth century C.E. Some studies claim that the written scripts of Arabic were known much earlier, around 2500 B.C., but on a smaller scale, as the Arabic language at that time was exactly the same Arabic at the advent of Islam.

Bearing in mind that all of the Semitic civilisations in Levant and ancient Iraq were Arab civilisations, and had been inhibited by Arabs since time immemorial, it is hard to identify exactly when and where the Arabic alphabet originated.

History, then, suggests that it was not Muslims who created the alphabet at the time of the advent of Islam due to the needs of the time. The very fact that the Holy Qur’an was recorded and successfully disseminated in Levant and Iraq without any language barriers posing problems, at the time of the Holy Prophetsa and then the Caliphs after his demise, proves that the Arabic language and alphabet predated them.

However, while there is solid evidence that the Arabic language and script are quite ancient, the accuracy of tracing the history of this rich language is very difficult; especially due to the biased studies and research of many orientalists and scholars who vehemently tried to deny the existence of the Arabs as a nation due to their distinct enmity towards Islam.

The Early Development of Arabic Scripts

If we look into the history of the Arabian Peninsula and the origin of the Arabic language, archaeologists have found inscriptions that show a close relationship between Arabic scripts and some earlier scripts such as the Canaanite, Aramaic and Nabataean alphabet, that were found in the north of the Arabian Peninsula. These inscriptions were dated as far back as the 14th century B.C.E.

Arabic Musnad

The first Arabic script, Arabic Musnad, which probably developed from the above-mentioned languages, does not possess the cursive aesthetic that most people associate with modern Arabic scripts. Discovered in the south of the Arabian peninsula in Yemen, this script reached its final form around 500 B.C.E. and was used until the 6th century. It did not look like modern Arabic, as its shapes were very basic and resembled the Nabataean and Canaanite alphabets more than the Arabic shapes.14

During the sixth and seventh centuries, the revelation of Islam had a major impact on the development of Arabic calligraphy. The Arabic alphabet is written from right to left like Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, and other scripts from the same linguistic family.

Early Calligraphic Script: Al-Jazm

The first form of an Arabic-like alphabet is known as the Al-Jazm script, which was used by northern tribes in the Arabian Peninsula. Many researchers think the roots of this script originate from the Nabatean script, and yet the early Arabic scripts also seem to have been affected by other scripts in the area, such as the Syriac script.

User Jastrow | en.wikipedia.org | Public domain work

Wikimedia Commons | Released under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0

The Al-Jazm script continued to develop until the early Islamic era in Makkah and Madinah in the west of the Arabian Peninsula.

In the first Islamic century, the art of calligraphy was born. The first formal scripts that emerged were from the Hijaz region of the Arabian Peninsula, most possibly from the city of Madinah. Those are early “Kufic” Qur’anic scripts and with a stately verticality and regularity in them called ma’il.

Other scripts, such as the Mukawwar, Mubsoott, and Mashq scripts, did not survive the progression of Islam, even though they had been used both before and during the early days of Islam.15

Other Known Early Islamic Scripts

Over the course of their development, different Arabic scripts were created in different periods and locations.

For example, before the invention of the Kufi script the Arabs had several other scripts, the names of which were derived from their places of origin, such as Makki from Makkah, Hiri from Hira and Madani in Madinah.

It has been narrated by Abu Hakima Abdi, that he used to write various books in Kufi. Once, Hazrat Alira should say after, fourth successor to the Holy Prophetsa saw him while he was writing, and said: “Try to write boldly and in a prominent manner, also try to make your pen beautiful,” so Abu Hakima cut his pen and started writing again. Hazrat Alira continued to stand beside him and then said “use the best ink with the writing pen and make the writing beautiful just as Allah has revealed his beautiful message.”16

Tumari was another script, which was formulated by the direct order of Muawiya, and became the royal script of the Ummayad dynasty.

Kufi Script

Kufi was invented in the city of Kufa (currently in Iraq) in the second decade of the Islamic reign, taking its name from its city of origin and, as mentioned earlier, was derived from an earlier script call Ma’il.

As a calligraphic historian, the problem remains of identifying calligraphy without dated, signed specimens. While we have the names of scripts such as Mukawwar, Mubsoott, Mashq, Jalil, Ma’il, etc., there is no way to definitively link them to known examples.

In the early stages of its development, the Kufic script did not include the dots that we know from modern Arabic scripts. If we examine Kufic script inscriptions, we notice particular characteristics such as angular shapes and long vertical lines. In addition, the script letters were wider originally, which made writing long content more difficult. Still, the script was used for the architectural decoration of buildings, such as mosques, palaces and schools.17

The grand impression in the Dome of the Rock is one example of early Arabic script—this monument, with the earliest examples of Qur’anic script and which was created only seven decades after the Hijra, was inspirational.

The Kufic script continued its development through different dynasties, including the Umayyad (661 – 750 C.E.) and Abbasid (750 – 1258 C.E.) dynasties. On this page, are some examples of Kufic scripts and their different developmental stages:

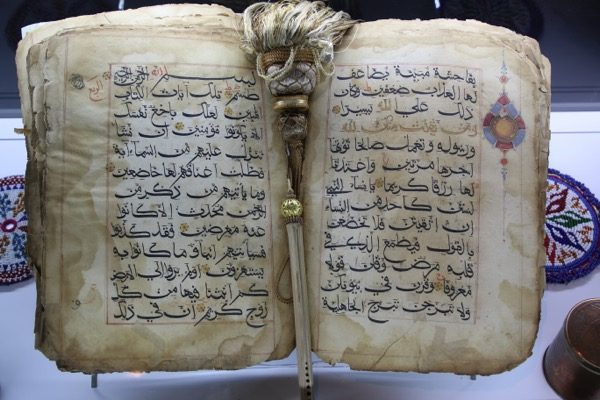

During the third century, the whole structure of calligraphy in the Islamic domains changed dramatically. Qur’ans were copied in huge numbers with various degrees of artistic skill. The thick, straight, flat Qur’anic scripts were introduced. Once paper was introduced, the use of parchment and vellum died out, along with their characteristic scripts.

Hussein Alazaat | Flickr.com | Released under Creative Commons BY 2.0

When the Dome of the Rock was restored by the order of the Caliph Al-Ma’mun (reigned 813-833 C.E.), a barely visible narrow belt of inscription was added in Thuluth script. This was eventually to become the most important script in calligraphy.

The Baghdad Period

For the historian, facts were better documented at the beginning of the 10th century C.E. Baghdad became the greatest city in terms of art, knowledge and sciences related to Islamic calligraphy. In the over 500-year-history of the Abbasid Caliphate, this city saw the emergence of the art of calligraphy as a fine art and the rise of the great founding teachers, admirers and their followers.

Ma’mun’s vizier Umar ibn Musida stated, in praise of Arabic calligraphy: “The scripts are like a garden of the sciences. They are a picture whose spirit is elucidation. The body is swiftness. The feet are regularity. Its limbs are skill in the details of knowledge. Its composition is like the composition of musical notes and melodies.”18

Pioneers of Islamic Calligraphy and Writing

Writing was very important during the early years of the evolution of Islam.

Some of the captives of the Battle of Badr could not afford to pay ransom to be freed but they could read and write. The Prophetsa told them that they would be freed if they each taught ten Muslim children to read and write. This was beneficial for both the captives and the Muslims. As a result, the captives taught the Companions to read and write in a very short time. By virtue of this initiative, the number of those who were literate in Madinah increased tremendously.19 Among them was Zayd bin Thabitra, who became one of the primary scribes to write down revelations to the Holy Prophetsa and worked on compiling the pages of the Qur’an. Although only a child at the time, the Messengersa of Allah appointed him to write down revealed verses, which allowed him to later fulfil the duty of the compilation of the Qur’an, enabling the Qur’an to be formatted in the book we see today. 20

Now in a very brief introduction, I will consider three major calligraphers’ work and their contribution to Islamic calligraphy.

Ibn Muqlah

Abu ‘ali Muhammad Ibn ‘ali Ibn Muqlah Shirazi hailed from Iran and was a statesman, poet, and calligrapher living in the late 9th century. In addition, he served as the vizier, or prime minister, several times under the reign of the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad.

Jessica Bordeau | Smashing Magazine | Released under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0.

One of his most important contributions to calligraphy was recognising that a system of proportion was needed that would allow people to easily copy and replicate scripts, while also making them easier to read and more elegant. His first script, therefore, obeyed strict proportional rules. In his system, the dot that we know today was used for measuring the proportions of the lines, and a circle with a diameter equal to the alif’s height as a measuring unit for letter proportions.

Ibn Muqlah’s system was incredibly important in the standardising of the cursive scripts. Moreover, his system made prominent cursive styles of writing, making them acceptable—and even worthy—for use in the writing of the Holy Qur’an.

Jessica Bordeau | Smashing Magazine | Released under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0.

Three elements together form the basis for proportion in Arabic calligraphy. The first is the height of the alif, which is a vertical, straight stroke that can comprise of between three to twelve dots. The second element pertains to the width of the alif, which is formed when the calligrapher presses the tip of their pen to the paper. The square impression left on the paper determines the width of the alif. The final element consists of the hypothetical circle that could be drawn around the alif, with the alif as its diameter. All Arabic letters should fit within this circle.

Ibn Al-Bawwab

Ibn al-Bawwab was an Arabic calligrapher and illuminator of the 11th century, and lived in Baghdad. He came from a common lineage and was a craftsman in his youth. In time, he also became an important religious figure. It is possible that that he was the first really significant artist in Islam. A skilled painter, he also pursued his artistic talents by both writing the scripts and illuminating his own works, which was rarely done by calligraphers of the era. Not only did he refine the methods of Ibn Muqlah, he also taught many students and is believed to have produced at least 64 written and calligraphied copies of the Qur’an.

In addition, Ibn al-Bawwab also was credited with the invention of both the Muhaqqaq and Rayhani scripts. Because of the consistency and beauty of the scripts, those penned by Ibn al-Bawwab were considered quite valuable and were sold for high prices even while he was alive. Working in all six styles, he is considered to have improved all of them, especially the Naskh and Muhaqqaq scripts.

Ibn al-Bawwab brought an elegance to Ibn Muqlah’s system and, while retaining the mathematical accuracy and precision of Ibn Muqlah, added artistic flourish and flair to the system. In this way, he was in part responsible for promulgating the contemporary method, in which the script maintains internal proportion by using the dot—made by the proper pen for the script—as the unit of measurement. Although Ibn al-Bawwab is said to have penned a large number of secular works in addition to the copies of the Qur’an he produced, only fragments of his secular work remain. As far as his Qur’ans, only one—written in the Reyhan script—has survived, which is in the Chester Beatty Collection in Dublin, Ireland.

Yaqut al-Mustasimi

The third great calligrapher was Yaqut al-Mustasimi, from the thirteenth century, also from Baghdad, who was a slave in the house of the last Abbasid caliph, al-Mustasim Billah.

The caliph was so inspired by his work that he gave his surname to him so that when, in the future, people praised his work, they would also remember him.

It is said that he wrote 364 written copies of the Qur’an. He transformed calligraphy yet again, bringing even more elegance to Ibn al-Bawwab’s method. Moreover, his “seven students”—the most famous seven of the many that he taught—are said to have disseminated his style (and their own versions of his style) far and wide, thereby making it the new standard. Unlike with Ibn al-Bawwab, he has left a multitude of authenticated works to study.

Committed to his work during the Mongol sack of Baghdad in 1258, he took refuge in the minaret of a mosque so he could finish his calligraphy practice. Several copies of his work still exist and are highly prized by collectors.

Other New Scripts

Around 1500 C.E, nearly two hundred years after Mustasimi, Turkish calligraphers invented a style called Diwani which was rather difficult to read. In order to set governmental or ministerial documents apart from ordinary documents, they made this script the official script of the Ottoman sultans. The other invention of Turkish calligraphers was a beautiful and decorative shape of twisted letters called Tughra, which was used to form the name of the Ottoman emperor, and was employed to authenticate the Sultan’s orders. It was used essentially as a seal or signature.

After the invention of Kufi script in Kufa and the spread of it throughout the Muslim world, the western part of the Islamic world did not experience any equivalent developments on par with the eastern area.

The western region in the Islamic world, including the whole of North Africa, used to be called the Maghreb, consisting of modern Libya, Sudan, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and even Spain.

It appears that a cultural separation occurred between Maghreb (west) and Mashregh (east) in the Islamic world. This separation is quite visible in terms of calligraphic development. So we have a beautiful Kufi script called Maghrebi Kufi and others, called Kairouani, Sudani and Fasi.

Six Major Scripts

Kufi (Place of development)

Thuluth (Width of the pen)

Naskh (Usage for Qur’an)

Deewani (Writing of the Court)

Riqa (Daily simple use)

Ta’liq (Hanging style script)

Kufic Script

The Kufic script is derived from the Hijazi Script, whose origin may be traced to Hirian, Nabatean and Ma’il, and as mentioned above, derives its name from the city of Kufa in Iraq.

Kufic is noted for its proportional measurements, angularity, and squareness. Kufic is one of the earliest styles to be used to record the word of God in the Qur’an. One of the early Kufic inscriptions can be seen inside the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.

under Creative Commons BY 2.0

During the first three centuries of the Islamic period (7th-9th century C.E.), the Holy Qur’an was written and recorded in Kufic script.

Library of Congress, African and Middle Eastern Division.

Thuluth Script

The name “Thuluth” (meaning “a third” in Arabic) refers to this style because one-third of each letter slopes and because it refers to the width of the pen used to write the script.

This script is called the king of calligraphy; it was first formulated in the 7th century C.E. and fully developed in the 9th century. Thuluth is a more imposing and impressive style. Not often used for long texts or the body of a work, it most suited titles or epigrams. As it evolved over the centuries, examples of its many forms can be found on architectural monuments of all sorts.

Naskh Script

Naskh means “copy” in Arabic. It is one of the earliest scripts, redesigned by Ibn Muqlah in the 10th century C.E., using the comprehensive system of proportion mentioned above. It is noted for its clarity in reading and writing, and was used to copy the Qur’an. In contrast to the Thuluth script, Naskh script would be used in longer body text.

Naskh means “copy” in Arabic. It is one of the earliest scripts, redesigned by Ibn Muqlah in the 10th century C.E., using the comprehensive system of proportion mentioned above. It is noted for its clarity in reading and writing, and was used to copy the Qur’an. In contrast to the Thuluth script, Naskh script would be used in longer body text.

Diwani Script

The name of this script derives from “Diwan,” the name of the Ottoman royal chancery. Created by Housam Roumi, this script was used in the courts to write official documents (as mentioned above) and reached the height of its popularity under Suleyman I the Magnificent in the sixteenth century.

Developed during the 16th century, it reached its final shape in the 19th century.

User cactusbones | Flickr.com | Released under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Ta’liq Script

Ta’liq means “hanging” and refers to the shape of the letters. It is a cursive script developed by the Persians in the early part of the 9th century. It is also known as Farsi (Persian).

The letters are rounded and have a lot of curves. While this makes it less legible, the script is often written with a large distance between lines to give more space for the eye to identify letters and words.

Nasta’liq Script

The Nasta’liq is a refined version of the Ta’liq script. Nasta’liq is the most popular contemporary style among classical Persian calligraphy scripts. Indeed, it is known as “bride of the calligraphy scripts.”

Shekasteh script

In the 17th century a more cursive form of Nasta’liq was produced called Shekasteh.

Riqa Script

The word Riqa means “a small sheet,” which could be an indication of the medium on which it was originally created. The Riqa style of handwriting is the most common type of handwriting. It is known for its clipped letters composed of short, straight lines and simple curves.

Riqa is a style that has evolved from Naskh and Thuluth.

Other Calligraphic Styles

Tughra was used by the Ottoman sultans as their signature. It was supposed to be impossible to imitate. For this reason, then, the tughra was often used as a stamp of authority and the royal emblem of the sultan. The genius of the tughra was that it was difficult to forge, and that meant that it could be used to authorise and legitimise anything from royal decrees to official coins of the realm. The official emblem would often include the name of both the sultan himself, and that of his father, along with the phrase “eternally victorious.”

These calligraphic symbols were so difficult to make that they required a special artist, employed by the court, to design and execute the tughra. An illuminator would then add colour, scroll designs and gold leaf, essentially “decorating” the tughra.

From the use of the first tughra in 1324, these forms became increasingly ornate and elaborate. The tughra shown above belonged to the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-566). It contains three vertical shafts and a number of concentric loops in complex, graceful, flowing lines.

Be sure to read the second part of this series next month in our July edition.

Endnotes

1.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calligraphy

2.Holy Qur’an, Surah Al-Furqan, Verse 33.

3.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tarteel

4.A Beginner’s Guide To Andalusi Calligraphy: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=Gc_fn-7M0S4.

5.Allama Ala wud Din Ali Bin Husam ud Deen, Kanzul-Ummaal, (Treasure of the Doers of Good Deeds), p486 and ref. no. 29566.

6.https://asiasociety.org/new-york/exhibitions/traces-calligrapher-islamic-calligraphy-practice-and-writing-word-god-calligrap. Accessed June 2016.

7.Allam Ala wud Din Ali Bin Husam ud Deen, Kanzul-Ummaal, p486 and ref no. 69558.

8.https://www.interlinkbooks.com/interlink_schami.pdf

9.Jurgen Wasim Fremgen, The Aura of Aliph: The Art of Writing in Islam, (New York: Prestel, 2010).

10.Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011).

11.https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2011/oct/09/steve-jobs-stanford-commencement-address

12.https://www.spiritilluminated.org/SacredArt.htm

13. Yasin Hamid Safadi, Islamic Calligraphy, Thames and Hudson, London, 1979

14.https://darwinpapasin.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/taking-closer-look-at-arabic-calligraphy.html

15.https://people.umass.edu/mja/history.html. Accessed June 2016.

16.Allama Ala wud Din Ali Bin Husam ud Deen, Kanzul-Ummaal, p.486 and ref no. 29559.

17.https://darwinpapasin.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/taking-closer-look-at-arabic-calligraphy.html

18.https://mohamedzakariya.com/essays/criticism-in-islamic-art/

19.https://darwinpapasin.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/taking-closer-look-at-arabic-calligraphy.html

[…] Mirza Masroor Ahmad, Worldwide Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community presides over the innovative calligraphy project led by Razwan Baig Sahib, in the Mubarak Mosque in Islamabad, […]

[…] Mirza Masroor Ahmad, Worldwide Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community presides over the innovative calligraphy project led by Razwan Baig Sahib, in the Mubarak Mosque in Islamabad, […]

[…] in a two-part article on the fascinating art and history behind Islamic calligraphy. first part is available here or see June 2016 […]