A lot of global political attention in recent years has been on China as it emerges as a heavyweight in the global economy. Mention is often made of its Muslim minorities in the West of China and their push for independence, but not many people know much about the background to Islam’s emergence in China.

This article provides an outline of how Islam entered China, how it has evolved, and the various ethnic Muslim groups in the country.

China is a huge nation of over one billion people in a country that spans most of Asia, over 3000 miles from West to East; in fact it is probably better to think of China as a continent in its own right. Being a Communist country, religion was actively discouraged for decades, and even now, is tolerated within limits. Islam, like Christianity, is a minority religion in the country. The main faiths are Confucianism, Daoism (or Taoism) and Buddhism. So how did Islam come to reach China and what are the conditions of the Muslims there now?

Chinese spirituality before Islam

The Chinese psyche is inclined towards commemoration of their ancestors and spirits. The traditional faiths of the Chinese included Buddhism, which had come via India, but also Chinese faiths such as Confucianism and Daoism. Chinese culture spans back many millennia and it can be daunting to make any sense out of their myths and legends, such as their fascination with dragons, but if you pierce through the mist of time, you will find that there are historical events and spiritual insights shrouded within these tales.

The Chinese started to absorb ‘formal religion’ at a time when prophets were active throughout the world. At a time when Socrates(as) was active in Athens, Krishna(as) in India, Zoroaster(as) in Persia, in China, Kung Fu-Tsu(as) (Confucius(as), 551-479 BCE) began to preach on the means of social harmony.

Confucius(as) left a legacy of moral teachings in his ‘I Ching’ on doctrine, duties of people to their family, neighbours, friends, rulers and government. He laid out a detailed set of guidance on marriage, music, wealth, learning and government. His message was that God had created order in the Universe, and man must understand his place and behave appropriately in order to progress. He discussed the concept of a ‘superior man’ in the following terms:

‘The superior man does not set his mind either for anything or against anything. What is right he will follow. The superior man is quiet and calm, waiting for the appointments of Heaven, while the mean man walks in dangerous paths, looking for lucky occurrences.’

Confucius(as) was followed by Lao Tzu(as) who laid the seeds of Daoism. So for many centuries, Buddhism, Confucianism and Daoism gained popularity across China. This began to change as China opened its doors to foreign cultures largely as a result of the opening of trade routes such as the Silk Route.

The Silk Route

Mere mention of the name ‘The Silk Route’ conjures up evocative images of camels, vast flat plains surrounded by mountains, colourful trading cities such as Samarqand and a flow of goods and ideas from East to West and back again.

China was well known for its innovation at the time that Islam was emerging out of Arabia and there is a well known quote attributed to the Holy Prophet Muhammad(saw):

‘Seek knowledge even if from China.’

Although there has always been robust debate about the authenticity of this quote, there is little doubt that the Holy Prophet(saw) would have been aware of China, as the Arabs had strong trading links with China via the Sri Lanka and Malaysia sea routes.

The Silk Route describes a number of overland routes that went from Turkey and the Middle East through Central Asia to China via Samarqand, Kashgar and Xi’an, and traders would journey for weeks and months on each epic trip. Often large caravans of camels were taken on these trips.

Spread of Islam into China

Many Muslims entered from the West of the country along the Silk Route. One such early pioneer was the companion Thaabit ibn Qays who died in 635 CE on his return from China and was buried in the Xingxing Valley east of Hami. His tomb is venerated by Chinese Muslims to this day.

Islam entered China through Arab and Central Asian traders. Actually, the first ‘official’ delegation went in 651 CE under the auspices of the 3rd Caliph, Hadhrat ‘Uthman(ra) who despatched Sa’d ibn abi Waqqas, the Prophet’s maternal Uncle.

He sent a message of peace to the Chinese Emperor encouraging him and his people to embrace Islam. The Emperor Yong Hui, in the second year of his reign, had no interest in adopting these foreign ideas and beliefs, but out of respect, responded by ordering the building of the Memorial Mosque in Canton City (Guangzhou), China’s first Mosque which still stands today. The Annals of the T’ang Dynasty make the first mention of the Muslim Arabs.

Part of the Annals of Kwangtung as recorded by Arnold read:

‘At the beginning of the T’ang dynasty there came to Canton a large number of strangers from the kingdoms of Annam, Cambodia, Medina and several other countries. These strangers worshipped heaven and had neither statue, idol nor image in their temples. The kingdom of Medina is close to that of India, and it is in this kingdom that the religion of these strangers, which is different to that of Buddha, originated. They do not eat pork or drink wine, they regard as unclean the flesh of any animal not killed by themselves. They are nowadays called Hui Hui …”

Canton (Guangzhou) became one of the first Muslim settlements in China as successive delegations visited through this city and were well received. The interest of the Chinese was more to do with trade opportunities than spirituality, and many of the early Muslims settled and married local women which helped to foster closer ties. As thousands of Arab traders settled in South China, these exchanges became more and more regular. An account from Abu Zeid Hassan in the 9th century describes boats laden with cargo from Oman heading for China from Basra and Siraf. The boats would take a route via India and Sri Lanka, then through the Malay Peninsula eventually to Canton and beyond.

Often the Muslims adopted the names of their Han wives or the nearest Chinese name or letter to their original Arabic names; for example settlers with the name Muhammad or Mustafa would often adopt the name Mu or Mo, those named Hasan would become Ha, Said would become Sai and so gradually, the names became integrated into Chinese culture.

A century later, the Annals again record that an ambassador called Sulaiman was sent by the Muslim Caliph Hisham in 726 CE to the Chinese Emperor Hsuan Tsung. Many years later in 756 CE, his son Su Tsung called upon the Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur to help him recover his capital cities. The Arab troops that assisted him remained in China, married local women and settled.

On the South Coast of China, apart from Guangzhou, Muslim traders also settled in Quangzhou, Yangzhou and Hangzhou over 1000 years ago and built their own mosques and facilities. Some also followed the Jinghang Canal northwards. Tens of thousands of Arabs lived in these cities at that time.

Often, Chinese rulers encouraged Muslim immigration for their own needs, so for example, in 1070, the Song Emperor Shenzong asked over 5,000 Muslims from Bukhara in modern Uzbekistan to settle in north-east China to act as a buffer between the Song and their enemies the Liao. These men were led by Prince Amir Sayyid.

Consolidation of Islam in China

Up to now, the Muslims were tolerated as foreign guests, but in the 13th century, having already taken control of the Muslim Middle East, the Mongol hoards devastated China. At this time, many Muslims from Central Asia were forced by the Mongols to migrate to Western China to assist with the administration of their empire. When Kublai Khan became the Emperor in 1259 CE in Khanbaliq (Beijing), he appointed ‘Umar Shams al-Din (commonly known as Syed Ajall) from Bukhara as his treasurer, and eventually as Governor of Yunnan, the region in the South-West towards Vietnam.

Before his death in 1270 CE, ‘Umar Shams al-Din had a great reputation as an honest leader who built Confucian Temples as well as Mosques in Yunnan. His family went on to strengthen Islam and his grandson obtained recognition for Islam as a ‘True and Pure Religion’ from the Emperor in 1335 CE. Other descendants went on to build Mosques in the city of Nanking.

The Muslims continued to consolidate their position on the coastal cities beyond Canton to the extent that when the traveller, Ibn Battutah of Morocco, visited China (probably after 1342), he reported that:

‘in every town there is a special quarter for the Muslims, inhabited solely by them, where they have their Mosques; they are honoured and respected by the Chinese.’

With the establishment of the new Ming Dynasty, it was the Muslim general Lan Yu who in 1388 led the Ming army to a decisive victory over the Mongols in their heartland beyond the Great Wall.

There had been a period of instability when the Mongols were removed from China as the Muslims were seen as their administrators. Ming Emperor Hung-Wu offered the Muslims many privileges and as their conditions improved, they were provided with new facilities and many new Mosques were built. These conditions continued to flourish throughout the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644 CE).

The Muslims learned to survive in a way that did not bother the local population. They dressed as Chinese, worked diligently and praised Confucius(as). The only outward differences were in the ceremonies of marriages and deaths, and the fact that the Muslims did not drink alcohol, gamble or eat pork. Also, Muslims were known for their focus on cleanliness. In that sense, it is surprising that they did not translate the Qur’an into Chinese, but continued to read in Arabic, something that drew attention to the community, particularly when times grew hard. Muslims retained a link to the rest of the Muslim world as every year, a small number would make the pilgrimage to Makkah by sea. They did not preach Islam outside of Mosque compounds, so this again reduced any potential friction with the authorities.

Chinese Mosque education (equivalent to sunday schools) called Jingtang jiaoyu was established in the 16th century through the perseverence of Hu Dengzhou (1522- 1597).

In the late 17th century, the great Chinese Muslim scholars Wang Daiyu, Ma Zhu and Liu Jielien wrote many books in Chinese on Islam and the Holy Prophet(saw). These books helped to increase the knowledge of the Chinese Muslims, although the wider population were still largely ignorant about Islam as the Muslims did not preach publicly.

Muslim Massacre

The downturn for Muslims began with the rise of the Qing Dynasty in 1644. Qing Emperors made life very hard for Muslims. First they prohibited the Halal slaughter of animals, then they banned the construction of new Mosques and the pilgrimage for Hajj.

Conditions grew bleak for Islam in the second half of the 19th Century when rebellion led to the slaughter of possibly millions of Chinese Muslims.

There was an uprising of Hui and other ethnic Muslim groups against the Qing Dynasty from 1862 to 1877 in the provinces of Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia and Xinjiang. There were many grievances and to some extent, the coming together of the different sects and ethnic groups was out of convenience, but it is claimed that they wanted to create an independent Muslim country west of the Yellow River.

Whatever their motivation, the rebellion was crushed, and estimates of the number of Muslims killed vary from 1-8 million. Many Hui and other ethnic Muslims migrated from Western China to neighbouring Russia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan from 1878 and their descendents still live there whilst maintaining their Chinese roots.

Things stabilised again after the fall of the Qing Dynasty when Sun Yat Sen established the Republic of China and told the people that the country belonged equally to all citizens, including the Han, Hui Muslims, Tibetans and the Mongols.

Modern Islam in China

As mentioned previously, China is a Communist state, and as such, faith was not encouraged and went underground for many years. The China Islamic Association was formed in 1952 but was forced to go underground in 1958. It was the reform years from 1978 that brought religion back to the surface. Five religions were officially recognised in China: Buddhism, Catholicism, Taoism, Protestantism and Islam.

The religions and their Mosques, Churches and Temples were revived, and many new converts were attracted to them. By 2000 CE, official estimates claimed that there were now 200 million religious believers in the country, 11% of those being Muslims. The largest community is the 9.8 million Hui Muslims, followed by the 8.4 million Muslims of the Uyghur in the West of the country.

Across the country, there are ten main Muslim groups: Hui, Uyghur, Kazakh, Kirghiz, Uzbek, Tatar, Tadjik, Dongxiang, Salar and Bao’an. In many parts of the country, they live separately and have limited interactions with each other in the same way that religious sects co-exist, but in the major cities where the Muslims are a minority, they often come together in unity realising that they have more in common than their theological differences.

In cities such as Beijing or Shanghai, the Muslims cannot be distinguished from ordinary Chinese as beards are not exclusive to Muslims, nor is modest dress exclusive to Muslim women. Perceptions of Muslims from the mainstream population are that they eat lamb kebabs and do not eat pork, and observe strict cleanliness. In Beijing, the Muslims of the city live in several pockets and are often involved in the butchery trade where they provide Qing Zhen (Halal) meat for their own communities and also ‘clean’ meat for the wider population who respect Qing Zhen.

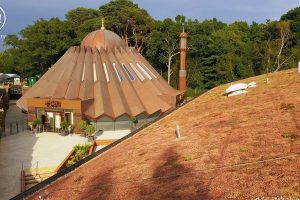

China has over 45,000 Mosques, most with a hybrid style of Arabic and Chinese. A typical example is the Niujie Mosque in the Hui district of Beijing which looks like a Chinese Temple from the outside, and on the inside has decorated pillars, walls and ceilings with red and other traditional colours, and gold Qur’anic lettering. The mosque dates from the 10th century and indeed the graves of two Arab missionaries are within the compound.

The main features of a mosque are there: a mihrab (niche), prayer mats facing Makkah, an ablutions hall, and a nearby Qur’anic School. The style is definitely Chinese and the minarets are built as pagodas and not that tall. One account describes that the Muslims did not build tall minarets so as not to offend the superstitious locals.

The mosque stands on a major crossroads in a Muslim area of Beijing not far from the Temple of Heaven, and across the road, there are Muslim shops and boutiques selling Halal meat, books and Islamic clothing (hijabs, hats etc).

However, the State is still wary of religion as a catalyst in breaking up the country (memories of the rebellion of the 19th century remain strong), and so maintains tight control over all clergy and religious instruction. Imams in China are educated at one of ten Qur’anic Schools where they are also educated in state law and religious policy. Imams attend regular meetings at the China Islamic Association and are also encouraged to attend inter-faith meetings to promote understanding and goodwill. Indeed many of the Imams are aged 20-40 unlike in the Middle East where they are often from the elders of the community.

China has also had some innovations such as women Imams who lead congregations of women in Mosques, but in general, the Muslims follow the same basic worship as Muslims elsewhere, and 10,000 attend the Hajj pilgrimage to Makkah every year.

There are many cities and regions in China that have maintained a significant Islamic heritage and a strong Muslim population to this day including Xi’an and the Xinjiang autonomous region.

Influential Chinese Muslims

Through the last thousand years, many of the Chinese Muslims played a significant role and are worthy of mention.

Zheng He

Zheng He (1371-1433) was a famous Hui Muslim explorer who led a fleet to explore the West from 1405 to 1433. Born in Yunnan in 1371, he was descended from Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din ‘Umar of Uzbekistan. His Arabic name is Hajji Mahmud Shams.

Between 1405 and 1433, Ming Emperor Yongle sponsored seven expeditions by sea to gain control of trade in the Indian Ocean. The expeditions consisted of hundreds of boats and possibly a crew of 28,000. The expeditions went to Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Persia, Arabia and East Africa. Historian Menzies suggests that Zheng He’s fleet even visited Australasia and the Americas although this is hard to substantiate.

There is little doubt that the establishment and development of Islam in Malaysia and Indonesia was influenced by the travels of Zheng He who established some infrastructure in Malacca, Palembang, Java, Kalimantan and the Philippines. He left many of his crew there who went on to establish Muslim communities propagating Hanafi Islam in Chinese.

Zheng He died at sea and was buried there, though a tomb and museum in his name exist in Nanjing. Even today, July 11th is celebrated in China as Maritime Day in honour of Zheng He.

Yusuf Ma Dexin

Yusuf Ma Dexin (1794-1874) was a Hui scholar from Yunnan who was fluent in Arabic and Persian.

In 1841 at the age of 47, he left with a small group for Makkah to perform Hajj. Unlike modern travel which is fast and easy, travel at that time was arduous; he had to travel overland to Burma and then took a steamship to Makkah. After performing Hajj, he remained in the Middle East for many years, studying at the Al-Azhar University in Cairo and then spent time in Jerusalem and Istanbul.

He returned to China where he became the first translator of the Qur’an into Chinese. He also wrote over 30 books on Islam in Arabic and Persian. He also compared Islam and Confucianism in an effort to build bridges. However, he also wrote strongly against the adoption of Buddhist and Daoist practices amongst Chinese Muslims.

Unfortunately he was also drawn into the Muslim Rebellion in 1856, and despite trying to reconcile the Muslims with the Qing leadership, he was considered a traitor and was executed in 1874.

Osman Chou

Muhammad Osman Chou, also known affectionately as Chini Sahib, comes from a line of Chinese Muslims in Shanghai.

In an attempt to gain a deeper education in Islam, he met Chaudhry Muhammad Zafrulla Khan in the Pakistan Embassy in China and, through his sponsorship, went with 5 other Chinese Muslims to Rabwah in Pakistan for formal training at the Jami’ah (Missionary Training Institute).

Since then he has written and translated several books on Islam for the Chinese people, including the Holy Qur’an. He has served with distinction as one of the most respected Ahmadi Muslim missionaries in Pakistan, South East Asia and the UK.

Chinese Muslim Cities

There are many cities in China with a strong Islamic heritage and an active population of Muslims, some of which are described in more detail here.

Xi’an

As tourism flourishes in China, Xi’an is a popular destination because of the nearby Terracotta Army. Actually Xi’an itself has a lot to offer in its own right. At the time that Arab traders were first venturing east to China, Xi’an was becoming a booming trade city with a population of over 1 million, and was at that time the capital of China.

Trade brought with it new people and new faiths, and at the time, the city had thriving minorities of Muslims, Zoroastrians (Mazdeans), Manicheans, Jews and Nestorians. However, its status was not to last, and by the start of the 10th century, the capital moved from Xi’an.

The population were intrigued by the foreign settlers, but those communities coexisted rather than fully integrating with the local Han Chinese, and their religious ideas were not really propagated. The explorer Marco Polo visited the city in 1278 CE and noted:

“The people are idolators and subject to the Great Khan …. There are two churches here of Nestorian Christians.”

There is still a thriving Muslim community in the city today, and the heart of the city hosts the Great Mosque dating from 742 CE, one of the oldest Mosques in the world.

Kashgar

Kashgar is a thriving town on the westernmost part of China in Xinjiang Province. Also known as Kashi, it had a strategic location on the Silk Route at the crossroads of the northern and southern Taklamakan routes. Once again, the Italian explorer Marco Polo visited here in 1275 CE and commented on the hard lifestyle of the people. The population of 250,000 are largely Uyghur.

The Id Gah Mosque holds 6,000 worshippers and is prominent in this Muslim city as the largest Mosque in all of China. It dates from 1442, and on Eid, anything up to 50,000 worshippers can be found praying largely on the floors outside this great old Mosque. The old Sunday Market reminds people of the role the city has as a centuries old trade hub sitting between the Uzbeks, Tajiks and Kazaks to the West, Pakistanis, Afghans and Indians to the South, and Chinese to the East. The city was also once home to Mahmud al Kashgarli (1008 – 1105 CE) one of the most respected Muslim scholars of his time.

Nanjing

The city of Nanjing is the capital of Jiangsu Province in eastern China. It became the capital of China in 1368 and probably the largest city in the world at the turn of the 15th century.

This was also the golden age of Islam in China, and Nanjing became a centre for Islamic study. In particular, there was a lot of interest in comparative studies between Islam and Confucianism. Muslim scholars brought an understanding from the rest of the Muslim world of science, mathematics, astronomy, architecture and medicine. The scholars of Nanjing were in a unique position to not just translate this knowledge, but to help the broader Chinese population to assimilate the knowledge.

Some of the early Mosques such as the Liuhe and Jingjue Mosques are still standing in the city. The Jingjue Mosque stands on Sanshan Street and was built in the 14th century. In fact its name was given by the Ming Emperor Zhu Yuen Zhang. Under the guidance of Zheng He, it was rebuilt, and then extended in 1492 just as Islamic Spain was taking its last breath in Europe.

Conclusion

The much-maligned Chinese are a very thoughtful, respectful and spiritual people. Although the political engine of China is facing criticism, the Chinese themselves are very disciplined and considerate and embrace spiritual concepts very easily.

It is interesting that despite being forced to go underground for decades under Communist rule (as did the Muslims of Central Asia under Soviet rule), since restrictions were lifted, the Muslims are back in strong numbers and with their culture and understanding of Islam intact.

Regular contact with the Middle East and South Asia has also ensured a continuous flow of information and active experience back into the Chinese Muslim community and a revival of religious zeal, though there is a difference amongst the Western Chinese who seek political leverage and the Eastern Chinese Muslims who seek to assimilate into main-stream society and practise their faith quietly.

References

1. Nicolle. D., Historical Atlas of the Islamic World, 2004, Mercury Books, London, UK.

2. Wilson. P., The Silk Roads – a route & planning guide, 2007, Trailblazer Publications, Hindhead, UK.

3. Guanglin. Z., Islam in China, 2004, China Intercontinental Press, Beijing, China.

4. Arnold, T. W., The Preaching of Islam – a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith, 1998, Aryan Books International, New Delhi, India.

5. Al-Djazairi, S.E., A Short History of Islam, 2006, The Institute of Islamic History, Manchester, UK.

6. Mackintosh-Smith, T., The Hall of a Thousand Columns – Hindustan to Malabar with Ibn Battutah, 2005, John Murray Publishers, London, UK.

7. Menzies, G., 1421 – The Year China Discovered the World, 2003, Bantam Books, London, UK.

8. Brash, G., The Sayings of Confucius, 1992, Graham Brashe (Pte), Singapore.

Mashallah!

very good article!!

please keep on writing!

Hmm it seems like your blog ate my first comment (it was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I had written and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I as well am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to the whole thing. Do you have any helpful hints for novice blog writers? I’d definitely appreciate it.