Shazian Baig, UK

Introduction

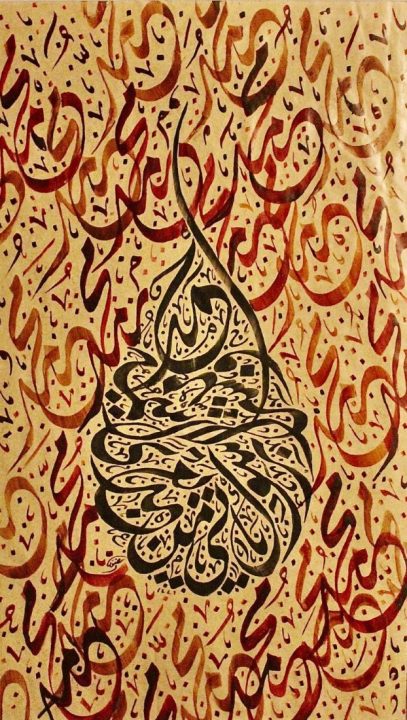

There is an art in the world which is unlike any other. An art form which combines aesthetics and esoteric expression. An art form which unites the pen and mind and soul. The name of this blessed art is Islamic Calligraphy.

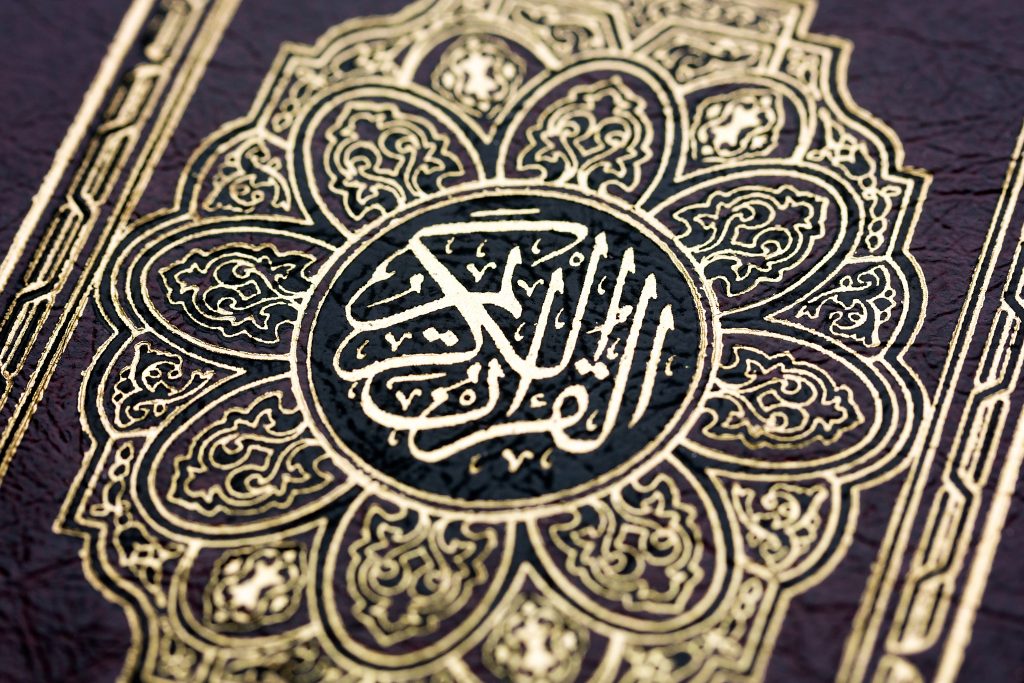

Almost everyone has observed and savoured Islamic Calligraphy at some point. Some have seen it adorned on the walls of mosques, some through calligraphic pieces displayed in their homes and others through observing the script in which the Qur’an is inscribed. Yet very few of us have been able to understand the intricacies encased within Islamic Calligraphy. Very few of us have been able to delve into the ocean of its knowledge and aesthetic.

Many individuals have defined Islamic Calligraphy in different ways according to their understanding and intrinsic experience. The word ‘Calligraphy’ is composed of the Greek words: ‘Kallos’ (beautiful) and ‘Graphe (writing).’ Therefore, Calligraphy can be understood as the beautification of the written form.

In Arabic, Islamic Calligraphy is described as ‘الخط’ which can be defined in a variety of ways. According to Edward Lane’s Arabic Lexicon, it can mean line, writing, streak, mark and a path. From these definitions, we can understand Islamic Calligraphy to be the beautification of writing in a proportioned way often leaving a mark and an impression on the scribe and the admirer.1

Islamic Calligraphy – Different Scripts

Visually, many different styles of calligraphy have been used for a variety of different reasons. Some have been to cater for a different geographical location whereas some have been through visions experienced from calligraphers themselves. These styles can be called the Scripts (Khat) of Islamic Calligraphy. These Scripts were then classified by the great pioneer, Ibn Muqlah, into the Al-Aqlam Al-Sitta (The Six Scripts).2 These scripts were: Thuluth, Naskh, Muhaqqaq, Rayhani, Tawqi, Riqa.

But in the modern day, the following scripts are considered significant:

Kufic

Kufic is regarded as the earliest form of calligraphy and had played a major role in the scribal tradition of manuscripts in the early centuries of Islam. It is named the Kufic Script due to being named after the city of Kufa in Iraq. The script was extensively used in the scribing of the copies of The Qur’an and reached excellence in the Umayyad and the Abbasid periods of Islamic Civilisation. The long, linear strokes in bold yet fluidic calligraphy was a major achievement and was achieved by cutting the Qalam (Pen) with a weakly-inclined oblique cut. Nearly all of the early manuscripts of the Qur’an were written on parchment and vellum and written in bifolios. All of these early manuscripts used the Kufic script and derivatives of the script itself.

The disadvantage of the Kufic script was the lack of diacritical marks (تشكيل) and dots (نقاط). This made for the Qur’an hard to read for large number of non-Arabs accepting Islam. They required a script that would allow for easy reading of the Qur’an.

Naskh

The Naskh Script, also known as the Nesih Script, is a revolutionary script that has changed the way we are able to read the Qur’an. It was redesigned and reformed by the pioneer of Islamic Calligraphy, Ibn Muqlah. The word ‘Naskh’ can be translated as ‘to copy’ and ‘replacement.’ These define the script perfectly: the script is used for the widespread copying of the Qur’an and it acted as a replacement for the Kufic script for the mainstream scribal tradition. The Naskh script was slowly refined in the hands of the pioneers Ibn Muqlah, Ibn Bawwab and Yaqut al Mustasimi. The Naskh script reached it’s loftiest heights in the hands of Ottoman Calligraphers. They were able to execute the fine features of the Naskh script in extremely minuscule letterforms. The master of the Naskh Script was Mehmed Şevki Efendi in the 19th Century. Calligraphers in the modern day use his calligraphy as a codex to understand the intricacies of the script.

Thuluth

The Thuluth Script is one of the most beautiful and majestic forms of Islamic Calligraphy and is often called the King of Calligraphy. The word Thuluth means ‘one-third’ as one-third of each letter slopes. The Thuluth script was often used for majestic inscriptions in manuscripts and ornaments as well as centrepieces in major monuments across the Islamic World. These includes Masjid al-Haram Makkah, Masjid an-Nabawi, The Dome of the Rock and the Taj Mahal to name but a few. The Thuluth script is often paired with the Naskh script when written in calligraphic pieces and manuscripts.

Thuluth, in the eyes of a calligrapher, has qualities unparalleled with any other script and is a royal script par excellence. It has a sweetness in the flowing strokes yet majesty in the vertical lines. Due to the intricacy and finesse required to master and execute this script, an extremely minuscule number of complete manuscripts were written using this script but colophons and titles were almost always written in Thuluth. Due to the grandeur of the letterforms, it was used as a go-to script when it came to application on architectural edifices.

Muhaqqaq

The word ‘Muhaqqaq’ is defined as ‘complete,’ ‘fulfilled’ and ‘correct.’3 The Muhaqqaq script is one of the greatly refined and majestic scripts of the Islamic Calligraphy tradition. The Muhaqqaq script is one of the earliest scripts to have come after the Kufic script. It was greatly used in manuscripts and reached its highest peaks during the Mamluk Sultanate. Several of the Mamluk period manuscripts have used the Muhaqqaq script in a majestic way often written using a bigger pen and using extensive gold illumination.

The Muhaqqaq Script was also extensively used in the Timurid period in which one of the most magnificent manuscripts, the Baysunghur Qur’an, was written. It is said that the Qur’an was written under the patronage of Emperor Timur (Tamerlane) and it is had a length of two metres and a width of a metre. It is one of the largest Qur’ans written and leaves of it can be found scattered amongst Iran and the western world.

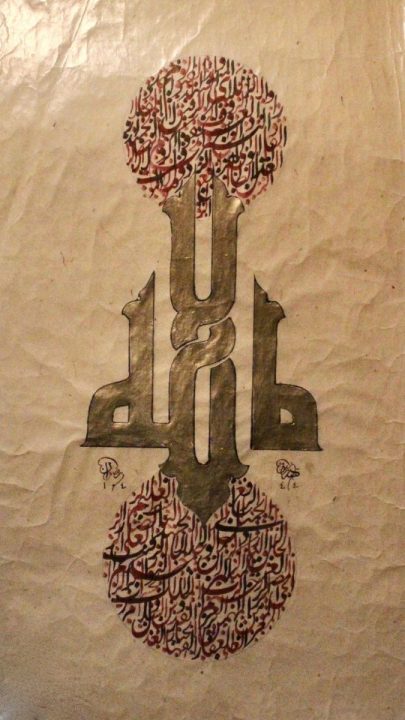

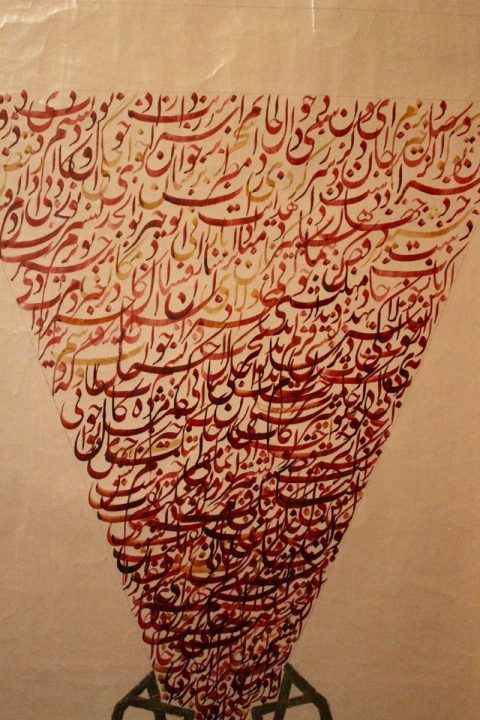

Nastaliq

The Nastaliq is one of the most romantic and poetic forms of calligraphy in existence. Its invention is attributed to the master, Mir Ali Tabrizi in the 14th Century. It is said he had wished to create a new script but was unable to do so after several failed attempts. Yet, one night, he had a dream in which Sayyiduna Ali, the Caliph of Islam. came in his dream and instructed him to draw letters that look like the wings of geese. After this dream. he followed the advice and created the Nastaliq Script.

The Nastaliq Script prospered in the hands of the Persians and was brought to the Subcontinent during the time of the Mughals. Slowly, a Dehlawi (Delhi) and Lahori (Lahore) style emerged which was much more linear and static compared to the Persian counterpart. Nowadays, all the text we see written in the Subcontinent and Persian lands are written in the Nastaliq script and is one of the most used and preferred scripts of calligraphy in the present day. It is used in general texts of books as well as in signage and typography projects. There is a major resurgence of the Nastaliq Script in Iran under the Anjoman Khoshnewisan Iran in which thousands of new calligraphers are being taught and certified.

Diwani

Diwani is a beautifully cursive and visually active script formulated by the Ottomans in the 16th century to be used in the Royal Court. It is an incredibly cursive script and often quite difficult to read. The reason for this was to create distinction between the common administrative writing and the esteemed royal writing.

At the inception of the script, the Diwani Script was not taught to everyone and it was considered a secretive script. It was only written by certain calligraphers who were subject to Royal Endowment. This allowed for the authenticity of the Royal Firman (Royal Communication) to remain intact and no forgeries of the letters from the Kings could be forged. Later, it became a great script to write Quranic verses and Islamic texts and is still being used in Royal Letters and Correspondence.

Riq’ah

The Riq’ah Script was a functional style of Calligraphy used in day-to-day activity. It was used in administrative faculties and was practiced by most professions associated with writing. In the Ottoman schools, all children were expected to be able to write in this script. The reason for its use in daily work was due to the simplicity, minimalistic and time-efficient manner in which the script was formulated. This was due to the short strokes and constantly flowing way in which it was written that allowed the pen to rarely leave the page within words. It is still being used today in administrative faculties as well as use in the writing of literature such as books and newspaper.

Tools

Tools play a major role in the practice of Islamic Calligraphy. Without the necessary tools, with the correct knowledge on how to use them, it is virtually impossible to reach the finesse required. There are many components of the tools required in Islamic Calligraphy:

Qalam

The Qalam plays a pivotal role in the practice of Islamic Calligraphy. The importance of the Qalam was established promptly at the origination of Islam in which the first Revelation mentions the Qalam (Pen). As well as this, Allah swore by the Pen in the Quran:

ن ۚ وَالْقَلَمِ وَمَا يَسْطُرُونَ

By the pen and what they inscribe 4

The Qalam can be made through many different materials. Reeds are often used which grow along the courses of water. These are then cut from the reed-bed and are left to dry and dehydrate to allow the reed to become hard and easy to carve. The drying process predominantly happens by burying the reeds until they are dry.

Different regions produce different types of reeds and have different desirable qualities. An example includes the ‘Dezfuli’ Qalam which grows in the Dezful region of Iran. The Qalam is strong yet easy to cut and requires less maintenance than other types of reeds. Alternative materials include bamboo, rose stems, Java thorns and carved wood. These are then cut using a knife. This causes the opening of the Qalam to have an internal opening and a Qat. The Qat is the area in which the writing is executed and is cut in different angles according to the style of calligraphy that is needed.

Ink

Ink has played a pivotal role in the practice of Calligraphy. Many formulations of inks have been produced to serve the art. The reason for the importance of ink is that the Calligraphy has always served the Qur’an and the scribal tradition. It has always been of utmost concern that the inks used in writing the Qur’an should be long-lasting to allow for the copies of the Qur’an to remain undamaged and easily legible.

The main formulation of ink consisted of soot which was gathered and mixed with gum arabic in a tedious process including mixing, straining and dilution. The collection of soot ink reached new levels when the Ottomans introduced a new practice. When they built their large mosques, they were lit by oil lamps which let off large amounts of soot. The soot would blacken the walls and leave a deplorable effect on the aesthetics of the mosque.

To combat this, they built ventilation systems which would gather the soot in internal chambers and there would be days designated for calligraphers to come and gather the soot ready to be used for the preparation of the ink. This created a level of sanctity as the ink was associated with the mosque and was then used to scribe the Qur’ans which would often go back into the very same mosques.

Paper

Paper has played a revolutionary role in modern day calligraphic practice. Before the introduction of paper, animal skin known as vellum or parchment was used to scribe the Qur’an. This proved extremely costly and often several hundred animal skins had to be used just to write one copy of the Qur’an. With the introduction of paper from China to Samarkand in 751, it proved a more efficient, ergonomic and economic way to practice Calligraphy. The paper was often dyed using onion skins, pomegranates or other natural vegetable dyes. After this, it was stretched on a board and treated using the Ahar technique. This technique includes the application of wheat starch and Alum to the paper in a lengthy process. The paper is then left to age and is ready for writing after 3-5 years.

About the Author: Shazain Baig is a Calligrapher and Islamic Art researcher based in the United Kingdom. He is studying under the tutelage of the great Calligraphy Masters of the world from Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. His pieces have been exhibited internationally and are present in many private collections globally. He has a passion in Islamic History and Civilization and is currently studying medicine.

ENDNOTES

- An Arabic-English Lexicon by Edward Lane, Vol II

- Bibliographic Information Systems For Manuscripts In Turkey:Mehmet Emin Kücük:Page 36

- https://mohamedzakariya.org/pages/islamic-art

- Surah al Qalam 68:2

Add Comment