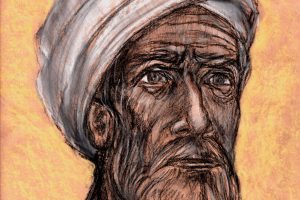

Ahmed Danyal Arif, London, UK

Following the current Covid-19 pandemic, theabrupt halt of commercial activity threatens to impose economic pain so profound and enduring in every region of the world at once, that recovery could take years. At this point, a recession – or two consecutive quarters of economic decline – seems like a truism.

Still, while the coronavirus clearly triggered the economic meltdown, it would be an egregious error to solely attribute it to the virus itself. The losses to companies, many already saturated with debt, risk triggering a credit crunch of cataclysmic proportions.

A world drowning in debt

While most important central banks — from the Fed to the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan to the European Central Bank — are now leaping into action as if the world were on fire, it helps to examine the subject of debt.

For years, expertshave warned that businessesaround the planet were developing a dangerous addiction to debt. Interest rates were so low that borrowing money was essentially free, enticing companies to avail themselves with abandon. Something bad was bound to happen eventually, leaving borrowers struggling to make their debt payments.

Something bad is now happening. As the coronavirus outbreak spreads, sending stock markets plunging and prompting fears of a worldwide recession, historic levels of corporate debt threaten to intensify the economic damage. Companies facing grave debt burdens may be forced to cut costs, laying off workers and scrapping investments, as they seek to avoid default.

However, simply looking at corporate debt levels is misleading. It is total debt that weighs on the economy. The whole economic model is sitting on a mountain of debt.

The American case is symptomatic of this complacency. It now requires nearly $3.00 of debt to create $1.00 of economic growth. This will rise to more than $5.00 by the end of 2020 as debt surges to offset the collapse in economic growth. In other words, without debt, there has been no organic growth.

In fact, a massive indulgence in debt is always creating a “credit-induced boom”. While the Central Banks believed that creating a “wealth effect” by suppressing interest rates to allow cheaper debt creation would repair the economic ills of a great recession, it only succeeded in creating an even bigger “debt bubble” a decade later.

The coronavirus crisis also highlights an ever more significant risk: world debt, which has never been so high. It was valued at $253 trillion at the end of 2019 (households, businesses and states included), according to the Institute of International Finance (IIF), with a debt / GDP ratio at 322%. A record. The rise has never been faster and can lead to a liquidity crisis that threatens the stability of this huge debt mountain.

And as if that were not enough, developing countries are on the hook to repay some $2.7 trillion in debt between now and the end of next year, according to a report released by the U.N. trade body. In normal times, they could afford to roll most of that debt into new loans. But the abrupt exodus of money has prompted investors to charge higher rates of interest for new loans.

Take the bull by the horns

The coronavirus crisis is reviving fears of a wave of defaults from emerging and less advanced countries, prompting a multitude of calls to creditors to extend deadlines, or even partially cancel the debt. There is an awareness that it is in everyone’s interest to avoid bankruptcy as much as possible, whether for private or public actors.

In Africa, debt ratios had returned to levels quite similar to those before the massive debt cancellations of the 2000s. Many African countries will find themselves in a difficult situation like Angola or Zambia. Same trend in other regions with Ecuador, under an IMF program, or even Sri Lanka, Tunisia or the Sultanate of Oman or Bahrain.

Although slaves are not shackled as they were in the past, it is clear than it has been replaced by an economic bondage and servitude. The relationship between most powerful nations and weaker countries has become akin to the relationship of a master and a slave. This slavery is presented as a sugar-coated pill and people willingly accept it. For the sake of one’s own convenience a person borrows from others but continues to sink in his loan, because the system of interest does not allow a person to emerge with his freedom.

Both the epidemic itself and the resulting economic crisis are global problems. They can be solved effectively by global co-operation and beyond the rationale of a vain economic doxa, which considers money as a tool of oppression, subjugation and injustice.

Certainly, there is a taboo concerning the mechanism of interest in economic debates. In fact, one reason is the deliberate choice by some economists to exclude any argument of moral nature. This discomfort actually reflects the fact that interest is a central feature of the capitalist system. Beyond the technical aspect of the question, it is a matter of knowing what would justify the fact that a significant part of the wealth produced by a nation falls into the hands of a few. Thus, the issue of interest becomes one of distribution and equity, and the discussion necessarily leads to a moral position in the debate.

As early as the 7th century, Islam took up the issue at the grassroots by forbidding all kind of interest. Interest is, in fact, like a leech which is sucking away the blood of humanity, and enables people with established custom and connections to go on multiplying their wealth practically without limit.

Unfortunately, despite the clearly visible harmful effects of interest, people remain entangled in the deadly web of interest, and do not ponder over the destructive impact that this financial system has at national and international levels.

The challenge of the 21st century therefore lies in inventing a mechanism for providing finance on an interest-free basis, which as previously stated Islam promotes. If man is able to apply such a mechanism, he would be able to unshackle himself from the bonds of money. It would usher in an era of human supremacy over money rather than money over human beings.

Let us also not forget that throughout history debt and war have been constant partners. Money-lenders are always creating circumstances which may cause conflict between one nation and another so that war can break out, and the belligerent nations may be compelled to borrow money from them.

Historically, nations got themselves into debt for the oldest reason in the book – one might even argue, for the very reason that public debt itself was first invented – to raise and support an army.The state’s need for quick money to raise an army is how industrial-scale money lending comes into business (in the face of the church’s historic opposition to usury). In the west, one might even stretch to say that large-scale public debt began as a way to finance military intervention in the Middle East – ie. the Crusades.

But the system of what appear to be easy loans makes it possible for governments to carry on ruinous struggles as they are able to obtain the sinews of war without having to resort to a system of direct taxation. During the war, the people of belligerent countries do not feel the burden which is laid on their backs. But after the war is over, their backs are bent double under the staggering weight of national debts and future generations are kept busy reducing the weight.

Conclusion

If the virus has decimated the world economy, for the time being, the debit bubble has held. However, as the economy takes a turn for the worse, it will become increasingly difficult for individuals and governments alike to keep pace with their payments.

Speculators are driven by greed and fear. And at the moment the coronavirus is sending shivers down their spines.

While we do have the ability to choose our future path, taking action today would require more economic pain and sacrifice than elected politicians are willing to inflict upon their constituents. This is why, throughout the entirety of history, every empire eventually collapsed under the weight of its debt.

Add Comment