The Mystery of the Prince

Why Prince Faisal declined to open the mosque, and pulled out only a few hours before the official inauguration, is a mystery. Although the Prince later on disclosed the fact that he had been instructed by his father, the King of Hedjaz, not to go ahead with the opening,[1] he never explained why he had been instructed to do so.[2] Therefore, despite much speculation around the incident, the reason behind this sudden change of plan, which led to the Prince dishonouring his commitment, was never disclosed. The speculation was intense – the absence of the Prince from the inauguration, which had supposedly been the main purpose for his long journey, made headlines in local and national newspapers. “Emir and a Mosque”, “Mystery of the Mosque”, “Emir Faisal Stays Away at Last Moment”, “Forbidden from Mecca”, “First London Mosque And Sect Dispute; Emir Forbidden to Open It” and “Prince Feisul Mystery” were some of the headlines given to the story by the mainstream press. As no explanation was given for the Prince’s absence in his memorandum, the press naturally turned to the authorities of the London Mosque to get their impressions on the incident. Hadhrat G F Malik(ra), Secretary of the Fazl Mosque’s administrative body, expressed his opinion that the King of Hedjaz had been pressurised by orthodox Muslims not to let his son proceed with the opening of a mosque that was being established by the Ahmadiyya sect.[3]

Hadhrat A R Dard(ra), the Imam of the Fazl Mosque, who was responsible for the arrangements of the opening by the Prince, stated that the King had accepted his request in August and had happily agreed to send his son, Prince Faisal, the Viceroy of Makkah, to inaugurate the mosque. Plans had been made accordingly, but on the very morning of the day the mosque was to be opened, he was suddenly informed by the Prince’s staff that King Ibn Saud had cabled the Prince, prohibiting his participation in the ceremony.[4] The Imam went on to say that both he and the Emir himself—and indeed, everybody else as well—were completely in the dark as to the real cause of the problem. Several suggestions were floated for the abrupt cancellation. It had been suggested that King Ibn Saud had been informed that this was not a real Muslim mosque. The Imam said that such a statement was nothing more than absurdity.[5] The Honourable Khan Bahadur Shaikh Abdul Qadir, also believed that the fact that orthodox Muslims disapprove of Ahmadis as Muslims could have been a factor behind this unpleasant situation, and that perhaps their “machinations have been responsible for preventing the presence of Prince Feisal.”[6]

Another suggestion, which the Imam was also informed of, was that Al-Ehram, a Cairo-based newspaper, had reported, with reference to the Morning Post London, that the mosque would be open to all religions for all types of worship, which meant it could not be classified as a mosque.[7] Another possible reason for the cancellation might have been the political significance of the Prince’s visit to England. Yet close scrutiny of India Office Records file of the Political and Secret Department reveal that political motives were negligible. Correspondence from then Foreign Secretary, Sir Austen Chamberlain, states in as many words that the Prince’s visit was taken to be untimely, and that it was tactfully communicated to the King, Ibn Saud, that the Prince could come to England but the visit would be classed as unofficial and incognito.[8] That the King accepted this condition makes it less likely that the Prince’s visit to England was undertaken for other political reasons, leaving the inauguration of the mosque as the prime reason of his visit.

Indeed, the absence of the Prince was notable in that even non-Muslims had anticipated the importance of the inauguration. For example, the Maharaja of Burdwan, who was also amongst the dignitaries attending the ceremony, said that he had taken the event so seriously that even though he was not a Muslim, he thought it was his responsibility to attend.[9] In short, while the opening of the London Mosque was laying the foundations of a culture of tolerance in Great Britain, it was also accompanied with a whiff of intolerance—not from predominantly Christian Londoners, but rather, ironically, from other Muslims themselves.

Indeed, the absence of the Prince was notable in that even non-Muslims had anticipated the importance of the inauguration. For example, the Maharaja of Burdwan, who was also amongst the dignitaries attending the ceremony, said that he had taken the event so seriously that even though he was not a Muslim, he thought it was his responsibility to attend.[9] In short, while the opening of the London Mosque was laying the foundations of a culture of tolerance in Great Britain, it was also accompanied with a whiff of intolerance—not from predominantly Christian Londoners, but rather, ironically, from other Muslims themselves.

First Mosque in London?

The London Mosque was named ‘Fazl Mosque’ by the Khalifa of the Ahmadiyya Community.[10] It was on 3rd October 1926 that the Adhan[11] was heard being called out for the first time in London from the minarets of a purpose built mosque.[12] One might reasonably assume that the London Mosque would receive the title of the first mosque in London. Yet recently, the East London Mosque has often been referred to as the first mosque in London,[13] based on the fact that the London Mosque Fund—originally set up in 1910—was later invested in the East London Mosque Project. Yet this claim is open to historical challenge, as K H Ansari correctly points out.[14] While there is absolutely no doubt that the London Mosque Fund was set up on 13th December 1910, with the first formal meeting of the Executive Committee of the LMF held in London[15]—nearly 16 years before the inauguration of Fazl Mosque—the setting up of the fund is not the equivalent of actually building a mosque. The fund could be taken as a means towards this particular end, but that too in the case that it had been initially dedicated to that specific project. Yet the project was open ended, set up with the intention of establishing a mosque. The famous jurist, Syed Ameer Ali, who later became the lifelong chairman of the LMF Executive Committee, is reported to have called attention to the need of a mosque in London in 1908; he put it as follows:

‘It does not require great imagination or political grasp to perceive the enormous advantages that would accrue to the empire itself were a Moslem place of worship founded in London.’[16]

In other words, the motive for this project was to establish some mosque in London—not any specific mosque—and two years later, in 1910, this project became the LMF. This was the motive behind the project for which a fund was formed later in 1910, namely the LMF. However, in order to figure out which mosque was really the first in London, it would be instructive to look at the history of the London Mosque Fund (LMF). After the initial excitement of a £5000 pledge made by the Aga Khan, contributions slowed and the LMF underwent a fairly static phase.[17] This amount was reached not before 1917 when the total amount received in donations totaled £5000.[18] Again, while initial enthusiasm was high, with the Begum of Bhopal contributing £7000 and the Ottoman Sultan and the Shah of Persia donating £1000 each, it receded fairly quickly due to various political and economic turbulences—the Balkan War and the First World War[19] among them. Moreover, it became more and more challenging to attract new subscriptions as Syed Ameer Ali’s position became more tenuous. The British viewed him as an activist with overwhelming Indian loyalties while the Muslims branded him a pro-British liberal.[20] Thus, when the LMF’s attempts to secure donations from Muslims in Britain and around the world failed, the only place they could turn to was the British government itself.

A letter from Lord Headley[21] to Sir Austen Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for India shows how clearly state sponsorship was demanded for the LMF.[22] How the State officials opposed the idea is also clear from the note[23] given by A Hirtze, a bureaucrat at the India Office and later Political Department, on the same letter. In other words, up until 1914, the LMF, practically speaking, was nothing more than a static amount of £5206 sitting in the form of cash or securities in the Bank of England. The LMF Executive Committee raised the issue of why there had been no progress, in its meeting on 30th April 1913. Indeed, no funds were put to any use until January 1914. It is then that the LMF committee agreed on giving Khawaja Kamaluddin[24] a sum of £120 a year to rent the Lindsay Hall in Notting Hill Gate (later moved to 39 Upper Bedford Place and then 111 Campden Hill Road) on Fridays for the weekly Muslim congregational prayer; Namaz-e-Juma.

Apart from the petty cash and administrative costs of the LMF Committee, this £120 remained the only expense used towards its actual purpose. But renting space was never the aim of the LMF. Indeed, even the proposal of purchasing a house for the purpose of a mosque was rejected outright by the Executive Committee on 12th May 1926, calling the proposal ‘an infraction of the Trust, the purpose of which is the building of a mosque.’[25] In other words, not even the LMF executive committee believed that renting a room or building a house was the same as actually completing construction on a purpose-built mosque. It is important to note here that this was in 1926, the same year that the Fazl Mosque in Southfields was inaugurated and had started functioning as a fully functional mosque. This should settle the matter; it is clear that Fazl Mosque was the first mosque in London. But while the construction of Fazl Mosque followed an easy path, the construction of the East London Mosque would take much more time. This alone leaves no room to doubt the fact that the Fazl Mosque was the first mosque built in London. The discussion of which mosque was the first to be built in London can be ended here; however, as there are a couple of decades still to cover before the opening of the ELM, let us continue with its history.

By 1926 then, the rent on Campden Hill Road, (where the fund had moved from their Notting Hill location) had increased to the amount contributed towards the rent of 111 Campden Hill Road, risen to £130 per annum[26] and the executive committee decided that it was not worth the expense, given the decreasing number of worshippers there, so they terminated the tenancy. The expense was beginning to seem to the Executive Committee as too much and not worth the value in view of the falling number of worshippers at the Campden Hill rented room. The tenancy with Messrs G N Watts Ltd, who worked as the agent of the property, was, thus, terminated. In the wake of the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Syed Ameer Ali tried to take other Muslim rulers on board as patrons in hope of getting donations[27] but this goal was not reached until 1928, when Lord Headley returned from India with a £60,000 donation from Nizam of Hyderabad. This was a sharp rise in the trajectory of the LMF, albeit in the monetary aspect only. But even here what cannot be ignored is that this donation was not given to the LMF itself—rather, it went to a new fund called the ‘London Nizamiah Mosque Trust Fund.’[28] This fund was partially used to purchase a piece of land in West Kensington and the foundation for a mosque, to be styled the ‘Nizamiah Mosque’ was laid in 1937,[29] but the ‘mosque itself literally never got off the ground.’[30]

Further attempts to seek British state sponsorship in a more tactful way than Lord Headley had adopted resumed in 1937 and 1938, by Margaret Farquharson[31] and Ibrahim Mougy[32] respectively. These attempts tried to shift the focus of the government officials from the religious side of the proposed mosque, to its potential socio-cultural and political aspects,[33] albeit to no avail. Next, Jamiat-ul-Muslimin appeared to further efforts and were the first British Muslims to be active in politics. The Jamiat-ul-Muslimin and Syed Hashim, the emissary of the Nizam of Hyderabad, both turned the focus of the LMF towards the East End of London and away from the proposed mosque in the centre of London.[34] It took a further five years for the LMF to eventually purchase a property on Commercial Road[35] and a further year to bring to it to a functional state. The new mosque, named the East London Mosque, housed its first Juma’ (Friday) Prayer on 23rd May 1941, and was formally opened on 1st August 1941.[36] As K H Ansari writes, ‘this, then, after thirty years, was the culmination of the LMF’s efforts.’[37] With this historical evidence, it is easier to conclude that the Fazl Mosque in Southfields, built by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, was the first mosque to be built in London, inaugurated and attended by noted Muslims more than a decade before the East London Mosque materialised.

Out of the Fold of Islam?

From a historical perspective, it is fairly clear that the Fazl Mosque was the first in London. The only other factor that would put Fazl Mosque’s status as the first in London into question is a theological issue. This question has to do with whether or not Ahmadis can be considered Muslims or not—a question that has also always been raised by other sects of Islam.[38] We see, however, that this question has always been asked of other sects. Fatwas, or decrees, by Muslim jurists, have always been issued by one sect of Islam towards another, declaring another group kafir (infidel or heretic). If these fatwas were to be given any weight, no Muslim would remain Muslim and, hence, no mosque could ever be classified as a mosque. One could argue that the difference with the Ahmadiyya Community is that all other sects unanimously agree on the fatwa issued against them.[39] While we do not have space here to examine this issue thoroughly, a detailed, theological debate can be had about this topic, however for the intents and purposes of this article, a brief understanding of how the Prophet of Islam defined a Muslim should suffice. When asked who was to be recorded as a Muslim in a census, the Prophet(saw)’s only criteria was that whoever claims to be Muslim should be recorded as a Muslim. On other occasions, the Prophet(saw) has defined a Muslim as one who bears witness that there is no God but Allah and that Muhammad(saw) is His Messenger, offers Salat,[40] pays Zakat,[41] performs Hajj and observes fasting in the month of Ramadan[42]. Ahmadis call themselves Muslims—thereby fulfilling the first criteria—but they also perform all the actions necessary to be a practicing Muslim, including implementing all the five pillars of Islam and acting upon all the commandments laid down in the Holy Qur’an. Indeed, hundreds of Ahmadis have been arrested in Pakistan for reciting the Kalima [the Muslim creed], displaying it on their mosques, or wearing it on a badge.[43] Ahmadis are constitutionally prohibited from performing any ritual or act in a Muslim way in Pakistan.[44] In short, under the aforementioned criteria of what constitutes a Muslim then, Ahmadis fulfil the definition of Muslims.

Also of particular interest is the fact that the Fazl Mosque in Southfields was inaugurated by the Honourable Shaikh Abdul Qadir, who himself was a prominent Muslim, but was not a member of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. He actually opened the mosque saying that he was opening it “in the name of the Merciful God.”[45] His address on the occasion is evidence of that the fact that he held no sectarian sentiments for or against the Fazl Mosque, and that what was important to him was the fact that the mosque would convey the message of Islam to the West.[46] Interestingly, this is the same Shaikh Abdul Qadir who was later requested to be on the board of trustees by the LMF in 1935 and formally attended the LMF meeting in 1936[47] for the first time. Hence, it is evident that the Fazl Mosque was considered to be a mosque by at least some members of the LMF itself at the time of its opening. Indeed, both at the inauguration of the mosque and decades afterwards, prominent Muslim figures such as M A Jinnah,[48] Sir Feroz Khan Noon, Sir Muhammad Iqbal, Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar, Muhammad Shafi (renowned Muslim Journalist), the Aga Khan, Muhammad Zafrulla Khan and A.K. Fazlul Huq, who attended the Fazl Mosque and even offered Namaz, the Muslim ritual form of prayer. Even Prince Faisal of Saudi Arabia, who had cancelled his appearance at the mosque inauguration, made it a point to visit the Fazl Mosque on a later state visit.

It was at this very mosque that Jinnah, after having withdrawn from Indian politics, informally announced his return to the Indian political scene by addressing the huge gathering of Indian Muslim students present at the Eid-ul-Adha[49] assembly at the Fazl Mosque.[50] He spoke at length on the British Government’s White Paper on Constitutional reform in India. This marked his return to Indian politics to take up the role that later proved vital in the formation of Pakistan.[51] Indeed, a vast majority of the Muslims living in Pakistan revere Jinnah as the leader of the Muslims of British India and later Pakistan.[52] It would be ironic and self-contradictory to then argue that Jinnah was not aware of who is and who is not a Muslim.

The Fazl Mosque Today

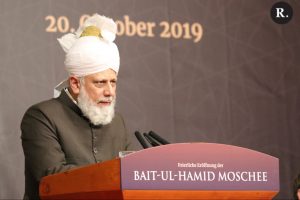

From the day of its inauguration, the Fazl Mosque has been a fully functional mosque, in which five congregational prayers are offered every single day. Since the shift of the Ahmadiyya Headquarters to London in 1984,[53] it has housed two Khalifas of the Ahmadiyya community: Hadhrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad(rh) (1928-2003), Fourth Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community and Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad(aba),[54] Fifth and current Head of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. Set deep in the midst of a unique and interesting historical heritage, London’s first mosque stands on Gressenhall Road SW18, reminding Londoners of the message of tolerance and harmony it brought along[55] all the way from the Muslims of British India, at a time when it was far more challenging to build a mosque than it is today.[56]

The history of the East London Mosque provides an interesting aspect to the whole story. The most poignant facet of it could be that a project; to build the first mosque in London; that did not materialise despite huge donations made by highly affluent and influential figures including the Begum of Bhopal, the Shah of Persia, the Aga Khan and their likes. Instead, the building of the first mosque in London materialised in the shape of the Fazl Mosque in Southfields, by the funds collected by the poor women of Qadian, India.[57]

Asif M Basit is on the Board of Directors of Muslim Television Ahmadiyya International, the official 24-hour satellite television station of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community (www.mta.tv), where he also produces and presents the weekly religious discussion programme, ‘Rah-e-Huda’ (The Right Path).

To contact the author, email abasit@mta.tv

Endnotes

- “First London Mosque,” The Times, October 5, 1926.

- “Mystery of the Mosque,” Westminster Gazette, October 4, 1926, 7.

- Ibid.

- “First London Mosque and Sect Dispute,” The Yorkshire Post, October 4, 1926.

- “London Mosque Mystery,” The Morning Post, October 4, 1926.

- Ibid.

- Mir Muhammad Ismail, Tareekh Masjid Fazl London, 1st ed. (Qadian, India: Book Depot Taleef-o-Isha’at, n.d.).

- India Office Records, British Library Political and Secret Department File IOR/L/P/11/270 The Foreign Office had written to the British Agent in Hedjaz that ‘offical visit of Amir Feisal before the conclusion of negotiations for revised treaty would hardly be desirable, nor would it be convenient at time of the year proposed. You should therefore do your best tactfully to discourage it.’ (Telegraphic message dated 19 August 1926)

- Ibid.

- Mir Muhammad Ismail, Tareekh Masjid Fazl London, 11.

- Islamic term for the call for prayer recited before the five obligatory prayers from a mosque.

- “London’s Voice from the Minaret,” The Daily Chronicle, October 4, 1926, 9.

- Humayun Ansari, ed., The Making of the East London Mosque, 1910-1951: Minutes of the London Mosque Fund and East London Mosque Trust Ltd, First ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2011), 1.

- Ansari, The Making of the East London Mosque, 1910-1951.

- British Library, IOR/L/P&J/12/468 fo., 40.

- The Times, January 5, 1911.

- Ansari, The Making of the East London Mosque, 1910-1951, 7.

- Westminster Gazette, December 20, 1917.

- Ansari, The Making of the East London Mosque, 1910-1951, 10.

- The Times, October 31, 1913.

- Rowland George Allanson-Winn, 5th Baron Headley who converted to Islam in 1913. The letter mentioned above was written in capacity of President of British Muslim Society to Sir Chamberlain.

- British Library, India Office Records, British Library Political and Secret Department File IOR/L/MIL/7/18861.

- Ibid.

- A missionary of the Ahmadiyya Community who came to England before the split of the Lahori Movement away from the actual Ahmadiyya Community, and who decided to join the Lahori splinter for the rest of his stay in Britain and his life

- Ansari, The Making of the East London Mosque, 1910-1951, 124.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 14; The Times, June 5, 1937.

- Ansari, The Making of the East London Mosque, 1910-1951, 15.

- Ibid.

- President of The National League-a London based non-Party organisation founded to pursue issues of national interests.

- London based Egyptian merchant, influential in cultural issues related to Arabs and Muslims.

- British Library IOR, L/P&J/12/468 fos. 216-217.

- Ansari, The Making of the East London Mosque, 1910-1951, 18–19.

- Ibid., 23.

- ELM Archives, brochure of the Opening Ceremony of the East London Mosque and Islamic Culture Centre, Friday 1st, August 1, 1941.

- Ansari, The Making of the East London Mosque, 1910-1951, 124.

- Ibid.

- The Journal of the Muslim World League (May 1974): 55–56.

- The obligatory prayer that Muslims are expected to offer from daily from dawn to close of the day at night, timing varying with the position of the Sun.

- A form of alms obligatory for eligible Muslims, eligibility being worked out on a certain level of static wealth.

- “The Book of Belief, Hadith No.8,” in Sahih Al-Bukhari (Darussalam Publishers KSA, 1997), 58.

- J. Ensor, Rabwah: A Place for Martyrs (London: All Parties Parliamentarian Group, 2007).

- 1997. The Pakistan Penal Code (XLV of 1860). ), (Lahore: PLD Publishers., 1997).

- The Daily Telegraph, October 4, 1926.

- “First Mosque in London,” The Northern Echo, October 4, 1926.

- Ansari, The Making of the East London Mosque, 1910-1951, 166.

- The Sunday Times, April 9, 1933; Madras Mail, April 7, 1933; Civil and Military Gazette, April 8, 1933.

- Muslim festival celebrated in the Islamic month of Zil-Haj to commemorate Prophet Abraham’s spirit of sacrifice in the way of Allah.

- The Sunday Times, April 9, 1933; Madras Mail, April 7, 1933; Civil and Military Gazette, April 8, 1933.

- Jinnah returned to India in April 1934.

- Jinnah is scarcely remembered by his name in Pakistan but very commonly called the Qaid-e-Azam which means ‘the great leader’.

- Friedman, Y, “Ahmadiyah,” in Encyclopedia of Religion (Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale, 2005), 200.

- ‘The Ahmadiyya Community believes that although the election of the Khalifa is through an electoral college, but the outcome is actually a manifestation of Divine Will’, (2012), [online], for further details, visit https://www.alislam.org/khilafat/fifth/ [23 February 2012].

- P. Johnston, “The Shadow Cast by a Mega-Mosque,” The Daily Telegraph, September 25, 2006.

- Ibid. ‘‘The first mosque was opened in Britain more than 80 years ago and there are now well over 1,000 – many converted from Anglican churches. London now has more mosques than any other western city. The biggest in western Europe is just a couple of miles from where I live in south London, on a five-acre site.’ The first and the last refer to the Fazl Mosque and the Bait-ul-Futuh Mosque respectively, both built by the members of the Ahmadiyyah Community.’

- Mir Muhammad Ismail, Tareekh Masjid Fazl London. The women of Qadian are said to have collected and contributed Indian Rupees equivalent to approximately £14,000.00 for the Mosque

Congratulations to the author for such a beautiful, fascinating and historical article about our beloved Fazl Mosque. I first entered it in 1968 as a very young man who had not yet become an Ahmadi muslim but

this mosque has been part of the fabric of my very existence since then.

Thank you so very much for this wonderful document and for the very high professional standard of it. You have truly enhanced the value of the article by providing full references and sources. May Allah reward you.

Jazakallah,

Muzaffar Michael Clarke