Professor Abdus Salam was a theoretical physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1979 on account of his groundbreaking contributions to the field of physics. An Ahmadi Muslim by faith and hailing from Pakistan, he also made history by becoming the first Nobel Prize winner of Pakistani origin. Recently, the English Heritage honored the legacy Dr. Abdus Salam by placing a plaque outside the family home, where he used to reside in London, in order to commemorate his achievements. The Review of Religions had the honor of speaking with Ahmad Salam, son of the late Professor Abdus Salam, about the tremendous honor of receiving a Blue Plaque and the significance behind it. Below is a lightly edited transcript of the conversation between Ahmad Salam [AS] and senior member of the Editorial Board for The Review of Religions, Sarah Waseem [SW[

SW: Ahmad Sahib, can I ask you if you could give us some background into how English Heritage, who put up the plaque, choose to commemorate figures?

AS: Yes, so it’s an open application process, where anybody can write in and suggest a name of somebody who they feel has had an impact on society at large. And, the only requirement from the English Heritage perspective is that they have to have been dead for a minimum of 20 years. I am not quite sure why they have that criteria but there it is, they have to be dead for 20 years. So, it has now been 24 years since my father died, and I then wrote to them, actually 4 years ago in 2016, to submit his name just as we got to the 20th anniversary, as somebody who, I felt, had an impact on society, and as a Muslim, there were very few Muslim scientists, scholars of any sort, recognised by English Heritage and I thought it was a great opportunity to raise the profile by applying to English Heritage.

SW: Thank you. And what is actually involved in that process? You’ve talked about the application but what happens next?

AS: It is literally an online application, you fill in the form, send it to English Heritage. Now, English Heritage is a charity that comes under I believe the Department of Media and whatever it is, I can’t remember exactly the name of the department [Department for Digital, Cultural, Media and Sports (DCMS)]. The long story short is that they have a very long, drawn out, investigative process. So they take all the applications, they then have a shortlist of the ones that they feel will fit the criteria, that goes forward to the committee, the committee then opines on it and gives it the green light to go forward to the next stage. And so going through a series of processes and at every stage, the team within English Heritage do an independent investigation and verification that the person contributed to society, made a difference, and then also that the person actually lived in the address; there is some verifiable way of showing that person actually lived in that address for a period of time.

British Heritage Logo ©Wikimedia Commons

SW: Right, that’s interesting. And so now you’ve got the plaque outside the house, so out of curiosity, what are the implications for that house now that you’ve got a plaque? In terms of any changes or whatever.

AS: Let me just go back to one other thing about English Heritage which is quite interesting. When they submitted the inscription that they wanted on the plaque itself, they misspelt Nobel Laureate. And they chose just to put “Champion of Science in Developing Countries”. And I insisted that we have “Nobel Laureate” on there because that, of course, was, to the outside world, one of his greatest achievements. So, we had a lot of to-ing and fro-ing because the plaque has to be a certain size, it’s a very heavy plaque and it’s actually cut into the house. The chap who installed it, he came around and he cut into the brickwork, so the plaque sits flush with the brickwork of the house. Now the plaque is probably an inch and a half or two inches deep, so he had to cut into the bricks by an inch and a half or two inches to make sure the plaque sat there. So the plaque itself is sort of restrictive as to how much freedom of movement they have around it. But I was able to persuade English Heritage that they had to put Nobel Laureate in there and they finally agreed, thankfully. And so we had ‘Nobel Laureate and Champion of Science in Developing Countries’. So it’s been wonderful for it to be included by them. In terms of your question, I believe there are only, out of 950-odd plaques in London, I believe there are only something like 4 or 5 where the families still have a connection with the house. So we are in a very rare position. So I’ve told my children, that now that you have your grandfather’s name outside the house, there is no way you’re going to be able to sell the house, whatever happens, so it’s just going to have to stay in the family’s hands for who knows how long for, but Insh’Allah forever.

SW: Yes, that leads me to my next question which is, can you tell us something about why this is significant in terms of history? Why you felt it was important to do this and what’s the historical significance of this?

AS: I think again, it’s very, very significant, especially right now because of the way that our community, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, is being persecuted in Pakistan. And just 3 or 4 weeks ago, there was a video circulating of some of the so-called elite educated youths of Pakistan, going to a poster of my father in Pakistan and getting black paint and just spraying it across his face, and recording it on their phones and then circulating it around social media. And the contrast between the image of that and the great upset that we as a family felt, personally, it genuinely brought tears to my eyes to watch this desecration of my father’s memory in Pakistan, and not by uneducated youth but these are university students who did this. And then a few weeks later, English Heritage were commemorating everything that he had done for humanity and for the society by putting a plaque up in his name. So, that contrast between the way my father was treated in Pakistan and the way he was treated in England, could not have been more of a contrast. And even now, 24 years after his death, he’s still being recognised in the UK and there have been wonderful messages, very warm messages, from a number of people from around the country, saying how wonderful it is; both Muslims, non-Muslims, Ahmadis and non-Ahmadis, all commenting on how wonderful this is as a tribute to Professor Salam.

SW: And that is the anomaly, that it is Pakistan isn’t it, because I understand, and correct me if I’m wrong, I understand that his name doesn’t even appear in physics textbooks in the country?

AS: It’s actually specifically been written out and this is why, as you may be aware, there are films being made, simply because nobody in Pakistan actually knows of Abdus Salam. The current younger generation, the generation Z of the world, are completely unaware of who Abdus Salam is and what his relevance is to Pakistan and what his role was in the development of Pakistan.

SW: And, you know, remarkably this is in fact, the film you refer to was the first film that has been made about his life. Am I right?

AS: That’s absolutely right and it’s interesting that there were two young Pakistani boys, Omar and Zakir, who came to me probably about 15 years ago and said “Look we want to make a film about Abdus Salam. We grew up in Pakistan, we finished our education in America, but we knew nothing of Abdus Salam when we were in Pakistan. And we could find nothing about him and we felt there’s a really important story to put together to tell the young generation of Pakistan.” So they then kept their day jobs going, one worked in the Bill Gates Foundation and one worked in Microsoft, and for 14 years they worked to raise the money to make the film, to buy archive footage wherever they could, and make this amazing film. Ultimately the plan was always to sell it to Netflix, so that the film would be shown in Pakistan because they knew that none of the local broadcasting units in Pakistan would ever take the film on because the backlash would be so great. They knew that Netflix would be the only people brave enough to show the film in Pakistan. That’s how it is now still available on Netflix. Sadly, because of commercial realities and because of commercial pressures, the original film was I think about 105 minutes, and the edited version came down to 90 minutes, but because of Netflix’s schedule requirements, it’s had to be cut down to 75 minutes. So it doesn’t quite flow in the way that we’d like it to but it’s a film made completely independently. We obviously had some contributions to the film, but the producers and the director took their own independent mind of how the story was to be told, and how the film was to be put together and there was no influence from the family whatsoever. One of the interesting things is that we as a family, we were very willing to contribute to the film, but they specifically said, “No, we would not take a penny from you as a family, we want it all to be externally funded.”

SW: Right. That is quite remarkable, isn’t it? And I wonder, has there been any kind of backlash in this country from the Muslim community against that plaque being put up?

AS: Not that I’ve seen and I’ve been delighted to see there hasn’t been any because I was a little bit concerned that this may be a target for people who wanted to protest against the community. But as of now, and we’ve had it in place now for a couple of weeks, certainly nothing that I’ve been made aware of, there’s nothing I’ve heard anyone comment about, no social media that I have seen, has been negative about it which is fantastic.

SW: You were telling me earlier that, just referring to that documentary film that’s been made, there’s also been quite a lot of response to that film, hasn’t there, also from other Muslims?

AS: Not just other Muslims, people generally. When they get to watch the film, non-Muslims, Jewish faith, Christians, Catholics, Protestants, whatever it is, whenever I’ve asked or whenever I’ve told people about the film, they’ve always been absolutely enthralled by the film, and absolutely amazed by the story told about my father but also the story of Ahmadiyyat that has come through the film, and the community and how the community has been so consistently attacked etc. So, it’s been a wonderful experience and of course, notedly people see the film and they meet me and have a coffee or something, and then they will say, “Right, when can we see you again, I’ve got so many questions to ask you about your religion and about your father and about his life.” So it’s been a wonderful tribute to him. And I guess, the blue plaque is just another example of that tribute to him.

SW: It’s definitely an eyeopener and it’s a film I would recommend people watching to learn about aspects of your father’s life. And I’m kind of wondering for the Ahmadiyya Jama’at of course of which he was a member, what do you think the significance of the placement of this plaque is for the Jama’at? And is he, do you think or do you know, the first Ahmadi Muslim to be commemorated in this way?

AS: Yes, but I’d like to think we could actually get some more and that’s in fact in the back of my mind to get permission from relevant authorities from within the community, to see if we can actually get some more plaques put up to commemorate people who’ve given so much back to society. But, everybody in the community, the number of texts and WhatsApp messages I’ve received of congratulations from around the world, from America, from Australia, from Europe, and obviously here in the UK, from Canada and from Pakistan, people just feel such a sense of pride, that by being able to share their feelings with me, have a little extra connectivity with this whole blue plaque process and they feel a great sense of pride and a great sense of joy that yet again, he’s being recognised and commemorated, even so long after his death.

SW: That must mean a lot to you and to your family and I wonder how your family respond is to this and particularly what your thoughts and feelings are that this plaque has been put up?

AS: I think it is a matter of great pride, and it’s something that I feel particularly strongly about being his son of course. And of course, as you know I have older sisters, they all got married and moved away, two of my sisters went to live abroad, so it was really my wonderful God-given gift to look after my father in old age and be with him in old age. And so I probably got to know more about him. In fact, one of my sisters said, “You’ve spent more time with him than we ever did, so you have got to record your memories of him.” But the point I feel is that, I have, with whatever time I have left, a responsibility of telling people about his legacy, and making sure that his legacy continues and making sure that my children know the story as well as I do, of all the wonderful things that he achieved and all those untold stories of his inspiration and his generosity and his giving back to society, etc. I make sure that I get that story out as much and as clearly as possible.

SW: They will be very interesting to read about and I hope that you will be telling us about those stories and publishing them. What do you think, had your father been alive, of course he couldn’t have been alive for the plaque to go up, but what would he have thought about it if he was looking down on us now, what would he be thinking about it?

AS: My sisters and I were musing about this saying what would our grandfather’s reaction have been? I think he would not have been particularly impressed because he did not believe in the worldly recognition, being singled out. For him, it was all about Allah’s recognition: what would you do in this life rather than sort of peer recognition. But we sort of felt that father would be mildly amused. He was never particularly enamoured with any kind of recognition as such because for him it didn’t matter. Everything he did in his life, all the awards he achieved, clearly he had pride in them and he accepted them with a very open heart. But they were always a means to an end. And the Nobel itself was a means to an end, and the means by which his profile would be raised, and the profile of what he was trying to achieve for third world science and development in particular and how he could make a difference to the world in one lifetime. So, to that extent it kind of fits in with that narrative.

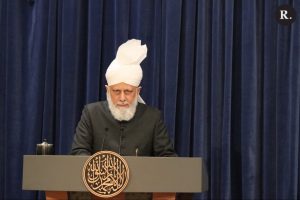

Professor Abdus Salam (1926-1996) ©Wikimedia Commons

SW: And, just to end, is there any special memory of him that you have and perhaps that you would be able to share with us?

AS: Oh, there are so many memories! I guess one that always – father had quite a heavy footstep and he would always rise very early in the morning and when he was here with us, we always had to make sure we were up early, clean, dressed, showered, and ready to work, whether it was holidays or whatever it was, it didn’t matter. We would always hear these heavy footsteps and we all jumped out of bed quickly, cleaned our teeth and whatever it was because we knew father was coming upstairs, and you could not be in bed. It was always living on the edge; when was fathers door going to open? When is he going to start coming up the stairs and are we going to be ready and sit down and look as if we’re reading a book or something, or studying something? So, lots of memories like that. Memories of him watching tv with me, watching Dad’s Army (British TV sitcom) or The Marx Brothers (American Comedy Act) etc. All wonderful memories that I have in this house.

SW: Jazak’Allah so much for sharing all of this with us and taking time out of your schedule to talk to us. We really appreciate this. And we’re really glad and feel very privileged that you have been able to tell us about this remarkable achievement, and we do wish you all the best for this. Jazak’Allah and thank you so much for talking to us.

AS: Jazak’Allah and thank you for the opportunity.

Add Comment