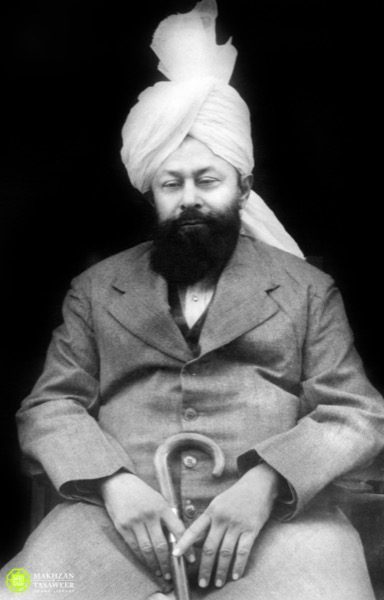

The Promised Messiah(as) paid a visit to Sialkot in September – October 1904. He was accompanied, among others, by the members of his family. It was on that occasion that I had my first glimpse of Hadhrat Sahibzada Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad Sahib, as he then was. I remember the exact spot and have a very clear recollection of how he looked at 15-16 years of age. I was only 11, and felt greatly elated at having been vouchsafed the opportunity of a look at so exalted a personage. I dared not contemplate the possibility of approaching and greeting him, any more than I could contemplate approaching and greeting the moon.

Thereafter, I used to accompany my father on his visit to Qadian in September and on the occasion of the Annual Gathering in December and had opportunities of observing the Sahibzada Sahib in passing, but could not muster enough courage to accost him. In 1907, I matriculated and moved on to Lahore and occasionally visited Qadian on my own, but this did not help to bridge the distance between us.

Indeed, my feeling of awe and veneration extended to all members of the family of the Promised Messiah(as) and to those nearly related or closely connected or associated with him. It was not till the late Sahibzada Mirza Bashir Ahmad Sahib joined the same college at Lahore in 1910, that I began to know any of them intimately.

In August 1911, I accompanied my parents (it was, I believe, my mother’s first visit there) to Qadian, to say goodbye, as I was proceeding to England for my law studies. It was on that occasion that, at the suggestion of Sahibzada Mirza Bashir Ahmad Sahib, I ventured to call on the elder Sahibzada Sahib, apprised him of the purpose of my proposed journey to England and requested him to pray for me. I was graciously received and was rewarded with appropriate words of wisdom and guidance. The meeting lasted only a few minutes. I ventured to write to him once or twice from England and was honoured with suitable replies.

In March 1914, Hadhrat Khalifatul Masih I(ra) died and Sahibzada Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad Sahib was elected to succeed him as Khalifatul Masih II. He received the homage and allegiance of 95 percent of the then membership of the Movement. I was, at the time, still in England and mailed my letter of allegiance to him the very day I received the news of his election. In those days, mail in either direction, between Qadian and England, took 17 days.

The First World War started on 2 August 1914 and leaving London on 8 October, I returned home in the beginning of November. It was a hazardous voyage; especially as the German destroyer Emden was active in Indian waters and had already destroyed several British vessels. The S.S. Arabia, by which I was travelling, arrived safely at Bombay on that occasion, but was sunk by the Emden during a later voyage.

In the course of my journey up from Bombay, I went first to Qadian and renewed my written covenant of allegiance to Hadhrat Khalifatul Masih II(ra), by oral affirmation. This was my first real meeting with him. While he had risen greatly in stature and was now my spiritual preceptor and master to whom I owed the deepest and truest allegiance of my heart and soul and to whom I was wholly devoted and committed, I felt far less shy in his presence than I had anticipated and found myself able to carry on my humble and respectful part in an intelligible manner in the conversation that ensued. I emerged from his august and gracious presence in a mood of spiritual exaltation and with a sense and assurance of complete security.

Half a century has since elapsed. This is an attempt at a brief personal memoir. Even that could extend far beyond the recognised limits of an article and, therefore, must be curtailed and con-densed so as to be confined within permissible bounds. I shall not here essay even an outline of the astonishing moral and spiritual revolution that has been compassed during that half century in the lives of individuals and communities in the near and far corners of the globe under the direction and guidance of that towering and dynamic personality. That task must be reserved for those much more conversant with the facts and vastly more competent to institute the necessary comparisons and to carry out the requisite appraisals and assessments, than I can claim to be…

It will be appreciated that as in the Promised Messiah(as) was fulfilled the prophecy concerning the second advent of the Holy Prophet(saw) foretold in (624) and we were accustomed to see in the former a spiritual reflection of the latter, so we expected to see his reflection in his Second Successor who is also his Promised Son and was in the words of the prophecy to be “in beauty and grace like unto” him. In this expectation, we have been in no wise disappointed and we have witnessed its progressive fulfilment. Of this, there are many facets. I shall here confine myself to a brief consideration of one or two.

Among other excellences of the Holy Prophet(saw), God has borne witness that:

…grievous is it to him that you should fall into trouble, ardently desirous is he of your welfare, towards the believers is he tenderly compassionate and merciful. (Ch.9: V.128)

I have experienced towards my humble self-witness towards other manifestations, too numerous to permit detailed mention here, on the part of Hadhrat Khalifatul Masih II(ra), of the qualities referred to in this verse. I proceed to draw attention to a few.

One winter’s day, many years ago long before Qadian was connected with Batala by rail, I went over from Lahore to Qadian. It happened to be the month of Ramadhan. I arrived about 4pm, an hour and a quarter before the fast was to terminate. Hadhrat Sahib, as was then his wont, stayed for a while in the Masjid Mubarak after the ‘Asr service and I presented myself to pay my respects. Immediately after graciously acknowledging my greetings he directed, with a smile, that I should be served tea. This was most unusual, and, besides, I was fasting. On my submitting this he exclaimed, with the suspicion of a twinkle in his eye and a tinge of gentle reproof in his voice: “Fasting, while you are travelling? What kind of fast would this be?” So tea was brought and in the midst of the company in the mosque, all of them fasting, he saw to it that I refreshed myself and also complied with the Qur’anic injunction in respect of postponing the fast when travelling. I was duly instructed and admonished, but how tender and affecting was the method of admonition!

In an appeal pending in the High Court, the title to over fifty acres of very valuable land, in a part of Qadian which was rapidly becoming residential, was in dispute. In the District Court, on first appeal, judgment had been adverse to Hadhrat Sahib and his brothers. The two issues arising in the case were those of fact and a second appeal had little chance of success. Hadhrat Sahib had been so advised but had directed the filing of the appeal as the late Sahibzada Mirza Sharif Ahmad Sahib (the grandfather of Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, Khalifatul Masih V) had seen in a dream that an appeal had been successful. The appeal was admitted to hearing. Hadhrat Sahib sent for me and told me that he had been advised that in view of the importance of the interests involved, Sir Muhammad Shafi or Mr. Petman (both at the top of the Bar at Lahore) should be retained to argue the appeal, but that he felt that sincerity and devotion should be valued above experience and desired me to conduct the appeal with Mian Muhammad Sharif Sahib to assist. I was deeply moved. Those were early days for me at the Bar and I had little experience of work in the High Court. To be chosen in preference to acknowledged and veteran leaders of the Bar was not a compliment to any merit that I might have been supposed to possess, but sheer generosity and affection on the part of my revered and incomparable master.

I felt nervous but was helped and cheered by the confidence that Hadhrat Sahib(ra) had placed in me and was strengthened by the knowledge that he would pray for the successful issue of the appeal. I was also greatly comforted by the help and support of my respected colleague, Mian Muhammad Sharif Sahib, who had been in active practice for some years, though, according to the then rules, I ranked higher in seniority. By the grace of God, our humble efforts were crowned with success.

At the time of the split, a small section of the Jama’at had seceded and had formed an association of its own with headquarters at Lahore. Among them was a gentleman in a fair way of business, who gradually drifted into a more than moderately comfortable stan-dard of living and became involved in activities of a more than legally questionable character. This led to his prosecution and conviction on a grave charge and he was sentenced to a long term of imprisonment. From the conviction and sentence an appeal was taken to the High Court, but bail was not allowed and pending the appeal, the appellant remained in jail. This proved to be his salvation. The contrast between his life in jail and his immediately preceding existence made him re-examine and overhaul his values. He retraced his steps and began once more to seek guidance and assistance through prayer and repentance. In the midst of his agony, he saw the Promised Messiah(as) in a dream and enquired of him: “Sir, when may I hope for deliverance?” “When even your skin is changed”, was the rejoinder. He interpreted this to mean that God demanded of him a complete revolution in his way of life and a reverting to moral and spiritual values. He made a firm resolve to carry this through and thereafter to adhere steadfastly to his chosen path. When his son came to see him the following visitor’s day, he related all this to him and made him seek an interview with Hadhrat KhalifatuI Masih II(ra), convey to the latter his father’s allegiance and implore him to pray for his deliverance.

It so happened that Hadhrat Sahib(ra) arrived in Lahore about that time and the young man came to see him, accompanied by the late Shaikh Mushtaq Husain Sahib (the revered father of our respected brother Shaikh Bashir Ahmad Sahib, till lately a Judge of the West Pakistan High Court). I was the only other person present at the interview. Hadhrat Sahib(ra) heard the young man through and in response to his piteous appeal for prayers for his father’s deliverance, gently uttered the comforting words: “I shall pray.” Hadhrat Sahib’s voice was scarcely above a whisper and indicated that he had been deeply moved. I was convinced that his prayers would be heard and would win acceptance, though the lawyer in me was curious to know how the concrete result would be achieved.

I was not retained in the case, but I had known the appellant and had some hearsay knowledge of the facts. The main point in the appeal was one of law. The principal witness in the case had, in his statement at the trial, failed to supply the essential links that would have connected the accused with the offence with which he was charged. A previous statement of that witness, made before a magistrate who had first taken cognisance of the case, did, however, contain those essential links. The prosecution had tendered that statement in evidence at the trial. The conviction of the appellant was based largely on that statement.

The appeal came on for hearing before Mr. Justice Petman. He held that the previous statement was not admissible in evidence against the appellant, and, as the rest of the evidence was not sufficient to establish his guilt, he accepted the appeal, quashed the conviction and acquitted the appellant.

A few months later, the same point came up for decision before a Division Bench (two judges) in another case, who overruled Mr. Justice Petman and held that the previous statement in that case was admissible in evidence. This, of course, did not affect the appellant who had been acquitted by Mr. Justice Petman.

That gentleman lived for more than forty years after his acquittal and carried through to the uttermost the resolve that he had made in jail; the inner and outer revolutions were completed and were sustained till the end which came last year, in the fullness of time when his new life, lived in the sight of God, in contentment and humility, devoted to the service of his fellowmen, had obliterated completely all traces of the temporary lapse for which he paid heavily and out of which he was rescued by the grace and mercy of God, emerging all the stronger for the searing challenge that he accepted and met fully.

I got to know him fairly intimately soon after the happy result of the appeal and marvelled at the change that had come over him. In truth, he possessed a childlike and lovable disposition and had no inclination towards vice of any kind. He stumbled, probably out of ignorance, but soon recognised that the path he had started treading did not lead to prosperity and security but to moral and spiritual bankruptcy. He was jolted back by Divine grace and mercy into the path of rectitude and righteousness and held fast to it so that in the end, all seemed well with him.

When the Duke of Windsor, then Prince of Wales and Heir to the British Crown, (which he never actually wore, for, as Edward VIII he abdicated before his Coronation), visited India in 1922, he was, during his stay in Lahore, presented a book on behalf of Hadhrat Khalifatul Masih II(ra) and the Jama’at, entitled A Present to the Prince of Wales, which contained a reasoned exposition of the teachings of Islam as a living faith and concluded with an invitation to him to accept it. The original was written in Urdu by Hadhrat Sahib(ra) and he sent a copy of the manuscript to me at Lahore with directions that I should translate it into English, as quickly as I could manage and then take the translation to Qadian for revision. It took me five evenings to complete the translation and I went over with it to Qadian. Two days were devoted to its revision. The revising board was composed of Hadhrat Sahib(ra), the late Hadhrat Sahibzada Mirza Bashir Ahmad Sahib, the late Maulawi Sher ‘Ali Sahib and our respected brother Master Muhammad Din Sahib. We started work each day immediately after Fajr Prayers, that it to say, an hour before sunrise and continued till late after ‘Isha’ Prayers, breaking off only for meals and prayers. We worked in the room that opens on to the roof of the Masjid Mubarak from the north. All meals were sent up from Hadhrat Sahib’s house and were served in the room in which we worked. We went out of the room and were separated from each other only during prayer-time. The sitting, except for these brief necessary intervals, extended over approximately 17 hours each day. I do not recall ever having spent two more diligent, more absorbing and at the same time, more cheering and more rewarding days.

The company was the best and most exalted and uplifting that could be wished for. The work, though exacting, was highly instructive and the arrangements for sustenance, though simple, were most agreeable and satisfying. Hadhrat Sahib’s eldest daughter, then a child of tender years, supervised the meals and her guileless gravity lent innocent charm and grace to each occasion. Hadhrat Sahib(ra) himself, though eager to squeeze out of each fleeting moment the best and utmost that it was capable of yielding, was most solicitous of everyone’s comfort and his sallies of good humour not only kept us in good spirits throughout but helped to expedite the work in hand. I can certainly affirm of myself, and I am sure it was true of each one of us, that at the end of each long day we came out as fresh, eager and cheerful as we had been at its start. This experience was repeated each time I enjoyed the good fortune of working in association with Hadhrat Sahib(ra). His scintillating personality has always had the effect of a refreshing and invigorating moral and spiritual tonic and his solicitude for those working with him has been deeply touching.

Forty years later, I had a brief meeting with H.R.H. the Duke of Windsor who was being informally shown round the United Nations Headquarters in New York. I mentioned A Present to the Prince of Wales to him. He recalled it immediately and affirmed eagerly: “I still have it with me”.

During the early years of Hadhrat’s Khilafat, a group of leading ‘Ulama, representing every section of opposition to the Movement, gathered at Qadian to deliver public addresses from a common platform, the purpose of which had been widely proclaimed in advance as the final uprooting of the Movement. This created a very difficult and delicate situation particularly from the point of view of law and order, as the meetings were designed to attract large attendance of hostile elements from the surrounding villages. The speeches might be provocative and one of the declared objectives was to exhume the sacred body of the Promised Messiah(as) to ascertain whether it had been safeguarded against the normal process of decomposition, as, so some of the ‘Ulama claimed, should be the case, if his claim to Prophethood was well-founded. There was not the least justification for the alleged belief of the ‘Ulama and the doctrine was coined merely to serve as a handle for a possibly contemplated wanton attempt at sacrilege. It was obvious, on the other hand, that any such attempted outrage would be resisted by the Jama‘at to the last drop of blood of the last surviving Ahmadi. Little reliance could be placed in this harrowing situation upon the willingness of the administration to help or upon the adequacy of the resources that it might deem it necessary to employ for the purpose. The District authorities should have banned the meetings of the ‘Ulama as soon as their purpose was known, but they did not do so, either because they failed to appraise the situation correctly, or because they were indifferent to it.

A heavy and excruciating responsibility lay upon the Jama‘at and it pressed most heavily upon its revered leader. I happened to be Warden of the Ahmadiyya Hostel in Lahore and received instructions to proceed to Qadian immediately in company with all the resident students of the Hostel. I announced this at the end of the Friday service and requested the students to board the evening train for Batala along with me. The University examinations were approaching and half the students were to sit for them, but not one missed the train. Shaikh Bashir Ahmad Sahib, then a resident of the Hostel, had gone home to Gujranwala for the day. He returned to Lahore in the evening and noticing some of his Hostel colleagues at the railway station went over to them and learnt from them what was required. He procured a ticket for Batala and joined us. The train arrived at Batala around midnight and some of the youngsters pleaded for a few hours’ respite before marching the eleven miles to Qadian. One or two felt it would be safer and wiser to wait for daylight before setting out on the uneven, sandy track that led to Qadian through an unfriendly area. I explained that “immediately” in my instructions admitted of no delay, and we marched on immediately arriving at Qadian just before the first flush of dawn. Even at that early hour, the town was in a state of alert. Fajr prayers followed and at the conclusion of the service we were allotted to various duties and stations.

I was put in charge of a party composed of a couple of reporters and half a dozen youngsters who were to act as messengers. We were to attend the meetings of the ‘Ulama throughout, and as the ‘Ulama had converged on Qadian in strength, the meetings continued from before sunrise till late into the night each day, with two brief intervals at noon and after sundown for prayers and meals. A magistrate and a handful of constables were also on duty at the meetings and it was part of my duty to draw the magistrate’s attention to anything mischievous or provocative that a speaker might indulge in.

During the two intervals, I would return to make my report to Hadhrat Sahib(ra), snatch a hasty meal and join in the services. Some time after midnight, Hadhrat Sahib(ra), having received and appraised reports from all quarters and sectors, would start his consultations and issue needful instructions. He would then make his round of check posts and satisfy himself that all was in order. The cemetery was, naturally, the centre and focus of attention and anxiety. The residential areas of Qadian were even then scattered far and wide, and security arrangements had to be elaborate, especially in respect of intelligence, liaison and contact. None of our people were to approach the place of the ‘Ulamas’ meetings, lest a clash or clashes should be provoked and in case of alarm or alert, scouts were to be immediately despatched to check posts in each sector to seek instructions which must be scrupulously carried out in an orderly manner with the utmost dispatch.

Along with others I was permitted to accompany Hadhrat Sahib(ra) on his rounds. It was an exhilarating and uplifting experience. 1 was deeply moved at finding such revered divines and scholars as the late Qadhi ‘Amir Husain Sahib, the late Maulawi Sher ‘Ali Sahib and many others of similar standing doing point duty! Syed Sarwar Shah Sahib was posted outside the Treasury of the Sadr Anjuman (Baitul Maal), standing upright without the suspicion of a stoop, like a youngster in his teens, his trousers drawn up to his knees, a dagger stuck into his belt, his rigid hand holding a lathi (staff) and his eyes bright and twinkling as ever. (May Allah be pleased with him and all that saintly company).

The first night’s round was concluded around 3 a.m. Hadhrat Sahib(ra) had taken note of certain weak links in the security chain and was anxious to strengthen them. Local resources were already completely mobilised and were fully extended. Help was needed from outside. Someone must carry and deliver oral instructions to trustworthy adherents within easy reach. One or two names were suggested but were not considered suitable. I ventured to submit the name of Chaudhri Bashir Ahmad Sahib, one of my student contingent. Hadhrat Sahib(ra) sent for him, gave him his instructions and directed that he should ride out at once, complete his mission and report to him immediately on return. Bashir Ahmad departed on the instant, stuck to the back of his pony for eight hours, made all the contacts, delivered the instructions and was back at Qadian submitting his report before noon.

By the time Hadhrat Sahib(ra) had concluded his instructions on the first night and had withdrawn to his devotions and supplications, dawn was fast approaching. Whether he was able to obtain any sleep I did not know. What I do know is that this tense situation lasted during three days and nights and that he, more than anyone else, was on the alert throughout, watching, reflecting, planning, devising, consulting, counselling, exhorting, cheering, encouraging and above all praying and supplicating Him in Whom all his hope and his trust were centred. The burden of responsibility was heavy and crushing, he carried it without flinching and discharged it to the uttermost.

Those of us who had the good fortune of being associated with him in our humble capacities, were, no doubt, anxious lest the least default on our part should add an atom’s weight to his responsibilities and anxieties and were thus eager to do our utmost, but had no feeling of fatigue or fear. With such a leader in charge every heart was uplifted, with love of him, of that for which he and all of us stood and for each other. The sense of common purpose, shared values and selfless devotion made every passing moment a repository of precious memories.

Further, there was the consciousness that our beloved and inspired leader was spending himself not only to safeguard the Movement and the Jama’at but equally to ensure the safety and security of everyone of those who had congregated at the Headquarters of the Movement under the mistaken notion that by inflicting any kind of damage or injury upon the Movement they would achieve a good purpose. He had no ill-will towards any of them; only love for all. Many of them would later be drawn into the ranks of the Movement with love for and devotion and obedience towards him.

The anxious days passed, but they left their precious remembrance in our hearts. My brave student contingent travelled back to Lahore with me. They had been on duty most of the time, some of them, including Mian ‘Ata Ullah Sahib, at the point of the greatest peril and, therefore, of the greatest honour, namely at the tomb of the Promised Messiah (peace be on him). None of them had had much sleep. This time we did not march back to Batala, but rattled along in bone-shaking springless carts, one of which, as often happened, overturned on the way inflicting a fracture on one of its precious occupants. We had to secure for him a berth in the train on which he could lie down and find some relief.

The University examinations were held a few days later. I kept track of those of my contingent who had to sit for them. Every one of them passed, including the one who had suffered a fracture. Blessings on them.

In the summer of 1924, Hadhrat Sahib(ra) was invited to represent Islam in the Conference of Empire Religions held in the Imperial Institute, London. He accepted the invitation and travelled to London with a party of divines and scholars, which included the late Sahibzada Mirza Sharif Ahmad Sahib, the late Hafiz Raushan ‘Ali Sahib, the late Maulawi Zulfiqar ‘Ali Khan Sahib, the late Chaudhri Fateh Muhammad Sial Sahib, the late Shaikh Yaqub ‘Ali Irfani Sahib, the late Bhai ‘Abdur Rahman Qadiani Sahib. Dr. Hashmatullah Khan Sahib and others. Chaudri Muhammad Sharif Sahib, Montgomery, was accorded permission to join the party of his own. Master Muhammad Din Sahib was called from America. The late Al-Haj Maulawi ‘Abdur Rahim Nayyar was in charge of the London Mission.

I was already in Europe and was directed to be available. A furnished residence, 6, Chesham Place, was rented for accommodation of the party. We were crowded, all arrangements were reduced to the minimum and simplest, but we were a happy and cheerful company.

Hadhrat Sahib(ra) and those accompanying him had taken time en route to visit Palestine and Syria and had made a brief stop in Rome. I had arrived in London in good time to welcome the party on arrival. It was a historic visit. It is much to be regretted that a detailed authentic account of it has not yet been published, though plenty of published and unpublished material is available for a whole volume.

I shall here confine myself to only one main incident. It must, however, be stated that it was a great privilege to be afforded the opportunity of being in the intimate company of Hadhrat Khalifatul Masih II(ra) and so many other eminent and revered personages for a period of several weeks. There was much to observe and a great deal to note and learn. One felt one was a member of a peripatetic spiritual academy. All manner of topics and problems, social and economic, moral and spiritual came up and were discussed, debated and pronounced upon. A discussion sometimes developed between Hadhrat Sahib(ra) and the late Hafiz Raushan ‘Ali Sahib in which the latter always sought to maintain his position with such cogency, clarity and pertinacity that no possible aspect was left unexplored. It was an intellectual treat to witness and derive benefit from the treasures of knowledge and learning which were drawn upon in clarification, support and refutation of a proposition as the discussion proceeded. One revelled in the whole process of illumination. It was a tremendously rewarding and enriching experience, enlivened throughout with sincere goodwill, deep affection and the common bond of allegiance and devotion that we cherished towards our beloved and revered leader.

Hadhrat Sahib(ra) had written his paper for the Conference in Urdu and I had been accorded the privilege of translating it into English. On the evening preceding the day on which it was to be read out I was summoned to Hadhrat Sahib’s presence and was told by him that the question under consideration was who should read out the paper at the Conference. He said it had been suggested that he should read it himself, but he did not feel quite at home in English and was not sure of his pronunciation of unfamiliar words. One or two other names had also been suggested and Hadhrat Sahib asked for my view. I submitted very respectfully that I would be the best choice for the purpose. Hadhrat Sahib intimated that the matter should be determined by a test. The two or three of us whose names had been suggested were asked to read aloud portions of the paper and scouts were posted at various points up and down the house, with, all intervening doors left open, to listen and report on the quality of the performance of each. I recall that the late Sahibzada Mirza Sharif Ahmad’s report was in my favour, except that he had noticed a slight huskiness in my voice. Hadhrat Sahib concurred and thus I was awarded the honour, subject to the direction that Dr. Hashmatullah Khan Sahib should look after my throat to ensure against any hoarseness developing.

Dr. Sahib took so serious a view of his responsibility that he started a series of energetic paintings of my unoffending throat with a strong nauseous tincture each application of which brought me to the verge of sickness. By breakfast time next morning I had endured three or four of these vigorous ministrations, and at breakfast felt compelled to appeal to Hadhrat Sahib against a continuation of the torture. My throat was in truth beginning to be hoarse in consequence of this sharp precautionary treatment. My plaint was received with a hearty laugh by Hadhrat Sahib and by everyone around the table, not excepting even Dr. Sahib himself, and my further penance was mercifully remitted.

The paper was to be read in the afternoon session of the Conference in the main hall of the Imperial Institute. There was a record attendance, every seat was occupied and a number of people had to stand in the wings, at the back of the hall and down the main corridor. My turn came and I stepped up to the lectern. My throat was dry and I felt nervous. Hadhrat Sahib(ra) was seated next to the lectern. Just when I was about to start reading, he leaned over and, in a tone the sweetness and gentlesness of which were at once soothing and heartening, said: “Do not be uneasy; I shall be praying.” This most affectionate gesture reassured me completely and I was able to proceed confidently with my task. The paper was listened to with rapt attention.

The moment the reading was finished people made a rush to the platform in their eagerness to greet and felicitate Hadhrat Sahib(ra). I descended from the platform and stood aside. A gentleman wearing an Edward VII beard and a cap, who had been standing at the farthest end of the hall during the reading, came up to me and shaking my hand with heartiness exclaimed: “I am somewhat hard of hearing and was standing away back; I heard every word clearly, and good eighteenth century English at that, no modern nonsense about it.” I was well content.

During the return voyage from Venice to Bombay, Hadhrat Sahib(ra), who was travelling first class, spent most of his time with the rest of the party, the greater number of whom travelled deck and had fitted up a comfortable arrangement under an awning on deck. One balmy evening, when the moon scattered its silver witchery over the waves, we foregathered on one of the smaller upper decks and at Hadhrat Sahib’s suggestion each one, with only my exception, recited a piece of poetry. In conclusion we begged that Hadhrat Sahib(ra) also recite a poem. With some hesitation he consented, but only on condition that we should lean over to him as he would not raise his voice so as to carry beyond three feet. So we gathered close around him and in a voice, low and brimful of emotion, he recited Ghalib’s ghazal.

When the last stirring vibration of that sweet and well-loved voice had been wafted away by the breeze, we came back to ourselves, as if released from a spell. Each eye was moist and each heart breathed a sigh. No one uttered a syllable. What each felt, words had not the capacity to convey. We came down in awed silence, cherishing the memory of a holy experience.

That was forty years ago, and one could spin on these enticing tales through many a page, but considerations of time and space call a halt. Besides, the heart that revelled in the consciousness of that gracious affection, the eyes that were used to witnessing that refulgent glory, the ears that were accustomed to hearing for hours on end the intoxicating music of that vibrant voice shrink from and protest against too lavish a revelation of their sacred and poignant memories to those who know him not as these have known him.

Going through this piece of write up, I felt like I was among them and wished I had at least the slightest chance of witnessing their presence.

May Allah give us the spirit and zeal to be like them, Amen