© Makhzan-e-Tasaweer

The year 1923 is very important in the history of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, for it was in this year that Hazrat Mirza Bashir-Ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra, Second Caliph and then-Worldwide Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, called for Ahmadis to actively work against the so-called “shuddhi” movement of the Hindu sect called the Arya Samaj, who intended to convert the Muslims of India to Hinduism at that time. Simultaneously, on the other side of the globe, a very historic event was taking place: a mosque was to be built in Berlin, which would be entirely financed by Ahmadi women.

For this task, Maulvi Mubarak Ali who was born in 1881 in Digdair, Bengal, was sent from London to Germany in September of 1922.1 After completing his studies at Presidency College, he joined the Teachers Training College in Dhaka to receive a B.A in teaching and education. In 1905, his first contact with Ahmadiyyat was made through the study of The Review of Religions.2 Subsequently, four years later, he visited Qadian and accepted Ahmadiyyat in the era of the first Caliph and then-Worldwide Supreme Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, Hazrat Maulvi Noor-ud-dinra. In the latter part of 1913, he took a one-year leave of absence and traveled to Qadian where he also worked on the English translation of the Holy Qur’an.

In 1919, he received instructions from Hazrat Mirza Bashir-Ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra to proceed to Nigeria via London.3 As his jouney to Nigeria was delayed for various reasons, it was decided that he should remain in London4 and work there, until 1922, when he was finally sent to Berlin. At that time, Berlin was a very cosmopolitan and international city, where intellectuals from different parts of the world resided.

Germany itself was still suffering from the aftermath of the First World War. After losing the war, significant political changes occurred. The monarchy was abolished and a democratic republic was declared. This era of German history is known as the era of the Weimar Republic. German foreign policy was still hostile towards the victorious powers. Hence, anti-British revolutionaries from the British colonies were warmly welcomed into the city, amongst whom many were Muslims.5 In these turbulent times, Maulvi Mubarak Ali arrived in Berlin with the aim of spreading the message of Islam in this part of Europe. He first took residence in Charlottenburg, a thriving and international borough of the city, in Dahlmannstresse 9.6 Two other Ahmadis, brothers Dr. Attaullah and Abdullah Butt, who were probably pursuing their studies, also resided in Berlin in the Hannoversiche Str. 1 near the Charité hospital.7 All three appear in the list of attendees of the meeting of the Islamic Society of Berlin in November 1922.8 Shortly after arriving, Maulvi Mubarak Ali succeeded in purchasing a piece of land near the tram station of Witzleben, which was at that time an agricultural land. 9 He bought it for £200 on 16th of February 1923.10 The architect K.A Hermann was assigned by Maulvi Mubarak Ali to design the mosque and after receiving the required permission, the excavation work for the mosque started on Friday, 27th July, 1923. Precisely at the same time, Hazrat Mirza Bashir-Ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra, second Khalifah and then-Worldwide Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, was delivering the Friday sermon in Qadian, in which he said about the Berlin mosque:

“How thankful we should be that in this short period, the weak and small part of a small community has collected the required amount and the construction of the mosque has started. I am mentioning this because I had written to be informed when the excavation work for the foundation starts, so that the Jama’at could pray for this work. Today a telegram came which stated, that at 9 o´clock Berlin time the excavation work would start. As the day there starts much later than here, 9 o´clock Berlin time means that at this time of Juma, is 9 o´clock there. Which means that the excavation work is just now being done. As this is the time of acceptance of prayers, I request the Jama’at to pray that God may bless this work and may Islam spread there stronger than Christianity did.”11

When we consider the blueprints12 of the mosque, it becomes evident what a tremendous and ambitious plan had been launched by Hazrat Mirza Bashir-Ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra, the Second Khalifah. It would have probably been the biggest mosque of the Jama’at at that time. The mosque had huge proportions; the minarets were approximately 60 metres high and a hostel for students was planned for construction in addition to multiple rooms for students and staff in the main building. In addition, a restaurant and shops had been proposed for inclusion on the ground floor. The mosque itself was on the second floor, bearing a huge dome of 13 metres in diameter. The costs for the mosque was estimated at £2500.13 As stated earlier, the money for this project was collected in a relatively short period of time, by the women of the Ahmadiyya community. The speeches of Hazrat Mirza Bashir-Ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra, the Second Khalifah, and the reports published in the Al-Fazal newspaper during those years, spoke volumes of the great sacrifices of the poor Ahmadi women of India. Hazrat Mirza Bashir-Ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra, second Khalifah and then-Worldwide Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community instructed the following words to be displayed on the mosque:

“This mosque is donated by the Ahmadi women for their new Muslim brothers.”14

Maulvi Mubarak Ali expressed this in his words stating: “This mosque will be a monument to prove that Muslim women have souls and that they not only care for their own souls but for the souls of their brothers and sisters thousands of miles away.”15

On the 6th of August at 5 pm, the official ceremony for the laying of the foundation took place. Maulvi Mubarak Ali had sent 500 invitations to various dignitaries, scholars and other people for this occasion. But there was also opposition to the mosque. In particular, a group of Muslims under the leadership of the two Indian brothers Abdul Jabbar and Abdus Sattar Kheiri, who not only had good relations with the German Foreign Ministry but were at times on their pay roll, opposed the mosque.16 Additionally, the Egyptian Dr. Mansur Rifat from the Egpytian Nationalists, was also against its construction. When Maulvi Mubarak Ali invited the different governmental officials to the ceremony, the German Foreign Ministry circulated a letter to different ministries on the 4th of August with the heading “very urgent” stating:

“The Indian national Mubarak Ali has purchased some months ago at Kaiserdamm a plot to build a mosque. He seems to have significant funds. The above mentioned is a representative of the sect of Ahmad the Qadiani, the founder of the reformist sect — named, after him, the Ahmadiyya Movement —among the Indian Muslims. The Muslims living in Germany dislike strongly Mubarak Ali and his friends, because he is seen in Muslim circles as an agent of the British government […] As we have learned from confidential sources, the local Muslims intend to counter rally on the 6th of this month during the foundation-laying ceremony. Therefore, it is strongly discouraged that representatives of the government take part in this ceremony or that the invitation of Mubarak Ali to the foreign ministry is answered.”17

Despite this letter, almost 400 people attended the ceremony, including a number of prominent personalities. Amongst them, the Secretary of State to the Interior Minister, Dr. Freund; President of the Brandenburg Province, Dr. Maier; the Afghan Ambassador Ghulam Siddiq Khan; Imam of the Turkish Embassy, Hafiz Sükri Bey; Imam Idris from Bukhara;18 the Iranian Prof. Mirza Hassan from the Berlin University and the famous Orientalist, Georg Kampffmeyer, attended, only to name a few.19 A total of four Ahmadis were present at this ceremony; Maulvi Mubarak Ali, the brothers Dr. Attaullah and Abdullah Butt and Muhammad Ishaq Khan, son of Mistri Qutbuddin, who had travelled from Dresden to attend.20 Maulvi Mubarak Ali started the ceremony with the recitation of the Holy Qur’an, after which he gave a short speech in English about the purpose of the mosque.21 His speech was translated in German by Dr. Schoemls of the German Society for Islamic Studies. Afterwards Prof. Mirza Hassan, the Inspector of the Afghan students, Sayed Muhammad Hashim, and the Ambassador of Afghanistan spoke, thanking the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at for this great work. The architect of the mosque K.A. Hermann then introduced the building itself. The notes of Maulvi Mubarak Ali’s speech, some newspapers from that day, and German, Arabic and English coins were put in a casket which was placed in the wall near the mihrab [alcove built into a mosque for the Imam to stand and lead prayers] by Maulvi Mubarak Ali, Dr. Attaullah Butt, Imam Idris of Bukhara and the Afghan Ambassador. The ceremony concluded with a silent prayer led by Maulvi Mubarak Ali.22

However, as mentioned in the letter by the foreign office, this historic event was disrupted by some Egyptians under Dr. Mansur Rifat. Maulvi Mubarak Ali had hardly finished his speech when Dr. Rifat caused a disturbance, exclaiming that the mosque would not be a mosque but rather an English barrack. Rifat wrongly accused Maulvi Mubarak Ali of being an Agent for the British,23 trying to exploit the anti-British sentiment prevalent among Germans at that time. Eventually he was removed from the scene by the police and the ceremony continued.24 In the coming days, the ceremony and the incident were reported extensively in the press. Some newspapers remained neutral but others wrote against the Jama’at.25 Their biggest accusation was that the Ahmadis were agents of the English Government and thus against the independence of Muslim countries. Mansur Rifat also started publishing some pamphlets against the Jama’at in which not only were these accusations repeated but also the Afghan Ambassador was fiercely attacked for attending the ceremony.26 Mubarak Ali tried to refute these accusations in many of his private meetings in the days and months that followed, stating that Ahmadis were loyal to every country they lived in.27

Later in the year 1923, Malik Ghulam Faridra also arrived with his wife and young son in Berlin to support Maulvi Mubarak Ali.28 In 1924, both missionaries published a booklet called Refuting the Allegation that the Members of the Ahmadiyya Movement are a Spearhead of British Imperialism, in which they replied to the attacks of opponents such as Mansur Rifat.29 Before that a letter written by Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra to Mubarak Ali refuting these accusations had already been published in the Al-Fazal of 21st September 1923.30 In 1924, another small booklet about the beliefs of the Jama’at entitled Ahmadiyya Movement or “Pure Islam” was published by Mubarak Ali.31 These were the first Ahmadiyya publications in Germany.

The mosque project eventually fell victim to the hyperinflation which devastated the German economy in the year 1923.32 The walls had already reached a height of 2.5 metres, when the construction stopped.33 In early 1925 the constructed walls were demolished, due to an alteration of the plan34 by the company Hausgemeinschaft Witzleben GmbH.35 This company also ran out of money after the basic structure of the building had been constructed. Consequently, the site was sold off in a compulsory auction in July 1926. It was then bought by Charlottenburger Baugenossenschaft.36 Even today, apartment buildings of this company stand at the spot. Maulvi Mubarak Ali and Malik Ghulam Faridra left Germany. Both had also attended the famous Wembley Conference of Religions in 1924, and Maulvi Mubarak Ali left at the end of the same year. He went back to India where he pursued a successful career as a teacher. He was later appointed the Amir of the Bengal province and is to this date held in high esteem as a result of his piety.37 The German Mission itself was closed due to a lack of funds; a decision made after a discussion in the Majlis-e-Shura [Consultative Body of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community] of 1924. It was decided that for the time being, London should be established as the main European Mission.38

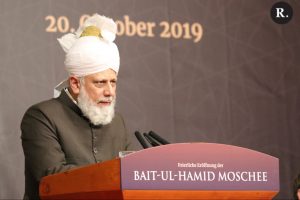

With the construction of Khadija Mosque in Berlin in 2008, the Berlin Mosque project was at last completed. His Holiness, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaba, opened the mosque in a big event, which was extensively covered by the media. The women’s organization of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at, Lajna Imaillah, had also financed this mosque project. Similarly, this project was also vehemently opposed, by right-wing and anti-Islam activists. A female Ahmadi architect designed the mosque itself,39 thus in this way, the second Khalifah’sra vision of the Berlin mosque was finally fulfilled.

Endnotes

- Al-Fazal (Qadian), November 1922.

- K.M. Mahmudul Hassan, Germanyte Prothom Bangali Missionery/First Bengali Missionary In Germany (1993).

- Al-Fazal (Qadian), 23 August 1922.

- K.M. Mahmudul Hassan, Germanyte Prothom Bangali Missionery/First Bengali Missionary In Germany (1993).

- Gerhard Höpp, Fremde Erfahrungen: Asiaten Und Afrikaner in Deutschland, Österreich Und in Der Schweiz Bis 1945, Studien / Zentrum Moderner Orient, Geisteswissenschaftliche Zentren Berlin e.V (Das Arabische Buch, 1996).

- Members list of Islamische Gemeinde, e.V. 04, November 1922.

- Al-Fazal (Qadian) 5 Oct. 1923. Members list of Islamischen Gemeinde zu Berlin e.V. 04. November 1922. Interestingly, the brothers Abdul Jabbar and Abdul Sattar Kheiri also lived at the same address, for more details see: Members list of the Islamische Gemeinde zu Berlin e.V. 04. November 1922.

- The Islamische Gemeinde zu Berlin e.V. was established in April 1922 by the brothers Abdul Jabbar and Abdus Sattar Kheiri.

- Letter of the District Court III, Berlin, 31 January 1927, 1. XV.15/A.1005.3.

- Ibid.; Maulvi Mubarak Ali, “Diary” (1923), 9; The Muslim Sunrise, January 1924, 14.

- Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra, “Friday Sermon of 27 July 1923,” Khutubat-e Mahmud Vol. 8 (Qadian), 146-147.

- The blueprints and construction files were found in a copy of the Islamarchiv Soest. For this the author traveled with M1. Ashraf Zia, Hafiz Fareed Khalid , Dr. Dawood Majoka and Ilyas Majoka in December 2015 to the Islamarchiv in Soest. Director of the archive Mr. S. Abdullah was very helpful in the research.

- Maulvi Mubarak Ali, “Diary” (1923), 9.

- Khutubat-e Mahmud, Vol. 8, (Qadian), 21.

- Ibid.

- Kris Manjapra, Age of Entanglement, German and Indian Intellectuals across Empire (London, 2014), 168.

- Letter of the foreign office, 04 August 1923, III E226 5/29.

- Maulvi Mubarak Ali writes him as Imam of Bukhara. In the Moslemische Revue of October 1934, his name is given as Imam Idris from Turkestan, who was the head of the so-called Tatar Camp (formerly Halbmondlager). The camp was for Muslim war prisoners of World War I.

- Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung 08 August 1923; Maulvi Mubarak Ali, “Diary” (1923), 15; Dr. Mansur Rifat, Die Ahmadia-Sekte (Berlin, 1923), 14.

- Al-Fazal (Qadian) 5 Oct. 1923. Maulvi Mubarak Ali, “Diary” (1923), 11.

- The speech itself was published in The Moslem Sunrise from January 1924. See: The Moslem Sunrise, January 1924, 13.

- Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, Berliner Tageblatt, Berliner Lokal Anzeiger, Vossische Zeitung, 07 August 1923; Maulvi Mubarak Ali, “Diary” (1923), 11.

- Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung Morning Issue, 07 August 1923. Maulvi Mubarak Ali, “Diary” (1923), 11.

- Ibid.

- E.g, Die Rote Fahne.

- See: Mansur Rifat, Die Ahmadia Sekte (Berlin, 1923); Mansur Rifat, Der Verrat der Ahmadis an Heimat und Religion (Berlin, 1923); Mansur Rifat, Die Ahmadia Agenten (Berlin, 1924); Mansur Rifat, Vollständiger Zusammenbruch der Ahmadia-Sekte (Berlin, 1924).

- Maulvi Mubarak Ali, “Diary” (1923).

- Al-Fazal (Qadian), 28 March 1924, 14.

- Mansur Rifat, Vollständiger Zusammenbruch der Ahmadia-Sekte (Berlin, 1924).

- For details see Al-Fazal (Qadian), 21 Sept. 1923.

- See Mubarak Ali, Ahmadija-Bewegung oder Reiner Islam (Berlin, 1924).

- Maulvi Mubarak Ali, “Diary” (1923), 22. For details on hyperinflation, see: Wolfgang CH Fischer, German Hyperinflation 1922/23: A Law and Economics Approach (Lohmer-Cologne, Germany: Eul Vehrlag, 2010).

- Maulvi Mubarak Ali, “Diary” (1923), 26.

- A. Mikowiak Baugeschäft Spandau, letter to the district office Charlottenburg, 26 February 1925.

- Hausgemeinschaft Witzleben GmbH, letter to the district office Charlottenburg, 15 January 1925; in the Mushawarat of 1924 this option was discussed. For details see: Report Mushawarat (1924), 46 – 47.

- Letter of district court III in Berlin, 31 January 1927, 1. XV.15/A.1005.3.

- K.M. Mahmudul Hassan, Germanyte Prothom Bangali Missionery/First Bengali Missionary In Germany (1993).

- Report Mushawarat (1924), 46 – 47.

- The mosque was designed by architect Mubashra Ilyas.

Add Comment